Whenever I find myself in my sons’ school, taking in the crayon scribbles that line the hallway, I think of this, from John Guare’s Six Degrees of Separation:

When the kids were little, we went to a parents’ meeting at their school and I asked the teacher why all her students were geniuses in the second grade? Look at the first grade. Blotches of green and black. Look at third grade. Camouflage. But the second grade—your grade. Matisses, every one. You’ve made my child a Matisse. Let me study with you. Let me into the second grade!

Both of my children are geniuses, but it’s true that the fifth grader’s drawings often look like advertisements (he sometimes appends fake social media handles to his pictures), while the second grader’s look like—well, Matisse covers it. His drawings disobey convention but possess their own logic. They look however they look, but they make sense.

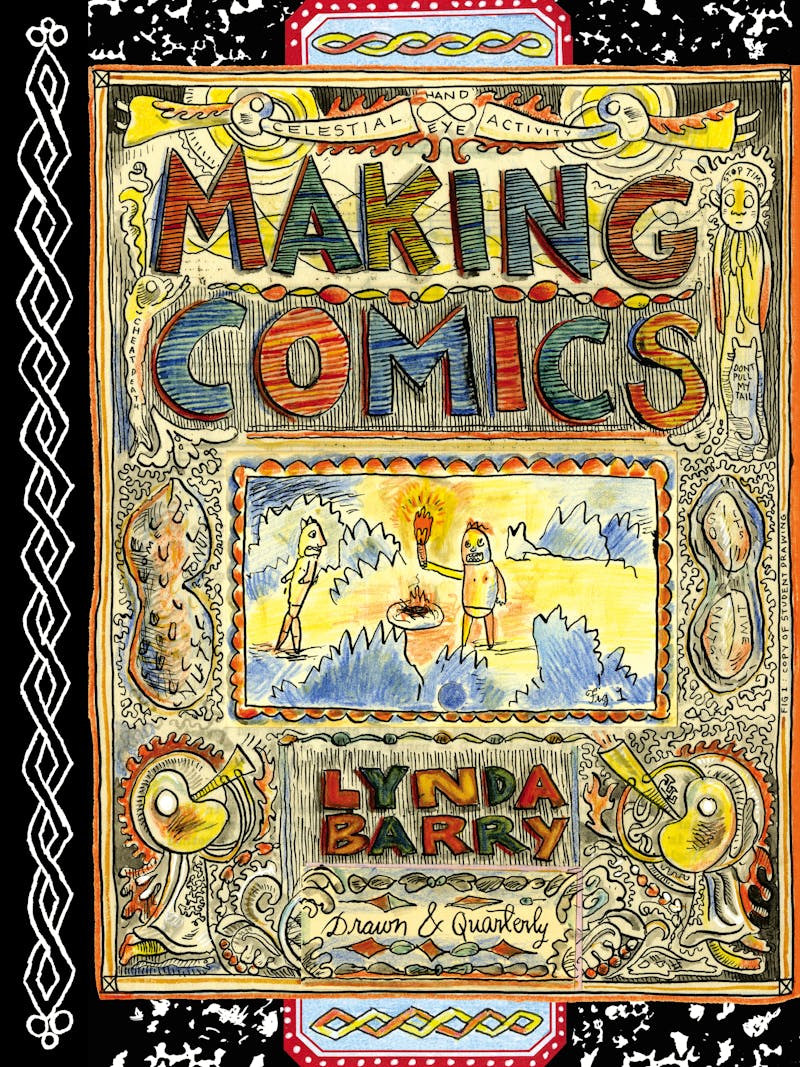

In her new book, Making Comics, Lynda Barry writes:

We draw before we are taught. We also sing, dance, build things, act, and make up stories long before we are given any deliberate instruction beyond exposure to the people around us doing things.... When these capacities are absent in a young child we worry about them. There seems to be an understanding that the thing we call the arts has a critical function for kids, though we may have a hard time saying just what it is, especially if we call it “art.”

Barry is a cartoonist whose work was a staple of the alternative newspapers when those still existed; she’s now an academic, though also something of a sage, interested in creativity, whatever that might mean to you. As the title suggests, Barry’s book is an instruction manual, but while Making Comics aims to teach you how to, well, make comics, it may surprise even the reader who has no intention of doing that (me). Barry is so thoughtful—philosophical, even—about art and its purpose that it’s hard not to be moved.

I have long loved Barry’s comics, especially those featuring her antiheroine Marlys. They’re funny, and weird, and messy, sometimes full of words and story, sometimes just captured moments that seem to mean something because the artist has bothered depicting them. In Making Comics, Barry rolls her eyes at her own style being designated “faux naïve,” and I can understand why: There’s simply too much calculation behind what Barry does to dismiss it as naïve, while faux implies something craven or calculated. This just feels inaccurate.

Still, I have also long been suspicious of Barry the life coach, as I am of all those “unlock your artistic potential” books out there. To pathologize your own creative frustration feels to me like an act of ego. If the muse eludes you, maybe you’re not blocked; maybe you just have nothing to say. Barry’s perspective is less cynical than mine. Maybe “humanist” is the word for it. If artistic expression plays some fundamental role in childhood development, shouldn’t it still matter to us as adults? There’s a reason people buy adult coloring books—even social media seems to scratch the same itch. Sure, it’s all performance, but drama is an art. Instagram lets us be Ansel Adams; Twitter lets us be Oscar Wilde.

Art saved Lynda Barry—“Everything good in my life came because I drew a picture,” she writes—and she only wants the same for everyone else. The book contains strict instructions (Barry is a benign tyrant): Close your eyes and draw the Statue of Liberty in one minute, draw yourself as Batman, scribble on a page then turn the random lines into a monster. Don’t evaluate the work you come up with. As Barry notes, “No matter what your skill level is when you begin, you can get an ‘A’ in this class. My final grade is based on where you began and where you ended up and what it is that you found.”

I do not draw (I want to start now!) but I found in this book a lot of smart advice that’s broadly applicable. On engagement with art: “The talking part of you knows very little about the gazing part of you that has something of a life of its own.” On technology: “You must take your phone off of and away from your body.” On keeping a notebook: “It’s a place rather than a thing.... You should try to keep it with you as much as you can.” I fear quoting these lines makes them sound hollow, as aphorisms usually do. But what’s most delightful about Making Comics is its emphasis on action, on exercise, on practice—on actual making.

It’s all far easier to access than, say, Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s Oblique Strategies, odd commands that prod users through creative block (“Ask your body,” “Disconnect from desire,” etc.) and that seem most useful to a stoner computer programmer. Barry works within the academy and won a MacArthur this year; she’s as establishment a figure as it’s possible to be. She’s clearly brilliant but uninterested in showing that off. Just as critics might misunderstand her style as naïve, they might misunderstand her pedagogy as self-help. I think Barry means what she says: “I believe anyone can make comics. The most lively work comes from people who gave up on drawing a long time ago.”

Both of my sons asked if they can have my copy of Making Comics when I’m done with it. They’re too young to parse the philosophy—“This language is what I’m trying to teach in my comics classes. This language moves up through your hand and into your head. Young children are native speakers.”—but the text is itself a comic, so some percentage of it is revealed to the eye. And as Barry knows, kids understand how to use that without being taught.

My kids and I attempted one of the exercises in this book together: Blind Bones, in which you close your eyes and spend a minute drawing a human skeleton in yellow marker. Then you repeat the same with an orange marker. Then a third time, using a blue marker. My kids were thrilled with the process—so odd, to set a timer, to not peek. I was thrilled with the results. Three Matisses.