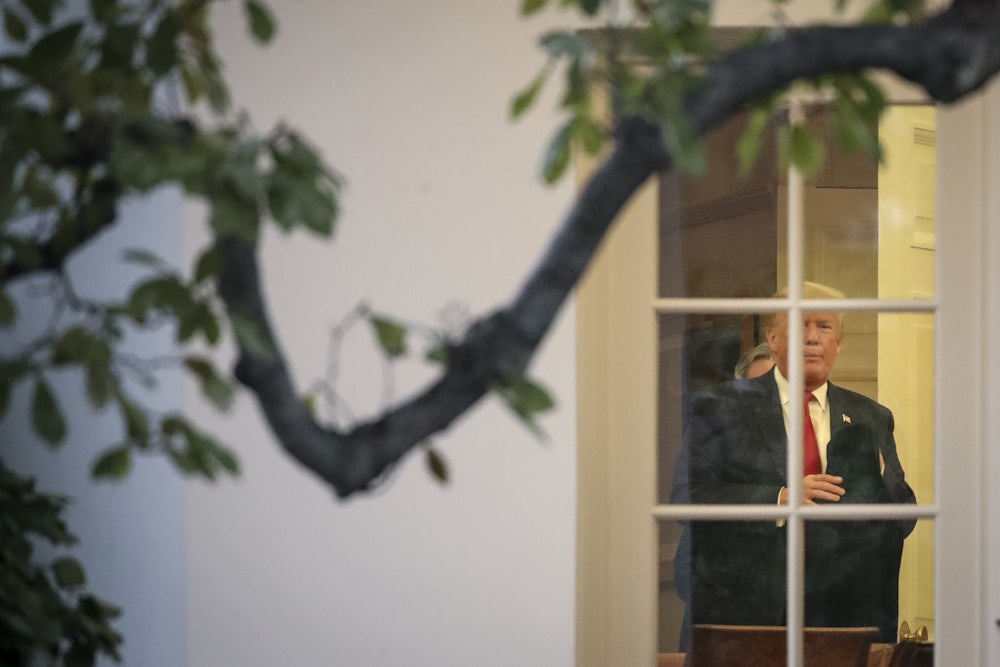

President Donald Trump closed out the first week of impeachment hearings with a self-inflicted wound. Marie Yovanovitch, the ousted U.S. ambassador to Ukraine, testified on Friday morning that she felt “intimidated” by Trump’s remark in a phone call with the Ukrainian president that she was “bad news” and “going to go through some things.” As if to underscore Yovanovitch’s point, Trump criticized her in harsh terms during the hearing, drawing allegations of witness intimidation. One Democratic lawmaker declared that Trump’s language toward Yovanovitch “would have embarrassed a mob boss.”

Soon thereafter, Trump demonstrated his Mafia-like approach to government in a more concrete way. That afternoon, he used his pardon power to reverse and prevent the punishment of three U.S. soldiers who were accused or convicted of committing war crimes in Afghanistan and Iraq over the last decade. The timing of the pardons, which came just hours after a federal jury in D.C. convicted his longtime political adviser Roger Stone of lying to Congress and hindering the Russia investigation, couldn’t have been more appropriate. They reaffirmed Trump’s commitment to omertà, the code of silence whereby those who report wrongdoing are castigated and those who commit it—whether on his behalf or in ways he supports—are protected.

Trump gave formal pardons to 1st Lt. Clint Lorance and Maj. Mathew Golsteyn of the Army, as well as a promotion to Navy SEAL Edward Gallagher. Lorance had already served six years of a 19-year sentence for murdering two men on a motorcycle in Afghanistan in 2012. Golsteyn was set to stand trial for hunting down and murdering an Afghan man after U.S. forces released him from custody. Gallagher escaped conviction on multiple murder charges but received a conviction earlier this year for desecrating a corpse; he was sentenced to time served and received a demotion that Trump’s move overrode.

It’s not the first time that Trump has pardoned an alleged war criminal. His aides framed the decision as an act of support for soldiers engaged in wars who might face similar allegations. “The President, as Commander-in-Chief, is ultimately responsible for ensuring that the law is enforced and when appropriate, that mercy is granted,” the White House said in a statement announcing the pardons. “As the President has stated, ‘when our soldiers have to fight for our country, I want to give them the confidence to fight.’” All presidential pardons are final and irrevocable.

Many observers quickly noted that Trump’s intervention in the military-justice system could foster a culture of impunity that shields soldiers who commit war crimes and other illegal acts on the battlefield. There’s a strong case that this is not a mere by-product of Trump’s pardons, but a goal of them. It’s well known that the president is no fan of the laws of war. On the campaign trail, he told supporters that the rules of engagement made it harder for U.S. forces deployed overseas to defeat the Islamic State and other foes. “The problem is we have the Geneva Conventions, all sorts of rules and regulations, so the soldiers are afraid to fight,” Trump complained during a Wisconsin town hall in 2016. “We can’t waterboard, but they can chop off heads. I think we’ve got to make some changes, some adjustments.”

Changing the laws of war themselves would be a formidable task that neither Congress nor the military’s senior ranks would support, of course. What Trump can do instead is make them far harder to enforce. In two of the three cases, other members of the soldiers’ respective units gave evidence against them or reported their actions to superior officers. Seven members of Lorance’s platoon testified against him during his court-martial, describing him as an inexperienced young leader who sought to prove himself during his third day in command with disastrous consequences.

Soldiers who served under Gallagher, the decorated leader of SEAL Team 7’s Alpha Platoon at the time, also tried to warn superior officers about his conduct on multiple occasions. They said they had witnessed him shoot unarmed civilians without provocation, including an elderly man and a young girl, and that he had murdered a defenseless prisoner in Iraq in his custody with a knife. Instead of taking action against an allegedly rogue officer, Navy officials initially responded by warning those who came forward that their careers and prized SEAL status could be jeopardized if they spoke out against a popular fellow commando like Gallagher. The president quietly reaffirmed that message with Friday’s pardons.

It’s no surprise that Trump would help enforce codes of silence to cover up wrongdoing. In September, he suggested to aides that the anonymous official who blew the whistle on his Ukraine dealings was a “spy” and hinted that they should be executed. Nor is this the first time he’s sought to use the pardon power to encourage officials to break the law in his name. The president reportedly told the top official at Customs and Border Protection earlier this year that he would be pardoned if he ignored judicial orders or federal laws to reduce border crossings or build the wall faster. Trump reportedly made similar comments to other top U.S. immigration officials as well.

Trump’s commitment to omertà reached its apex during the closing stages of the Russia investigation. In late August, former Trump lawyer Michael Cohen pleaded guilty to multiple crimes, including a campaign-finance charge, in which he implicated the president. That same day, a federal jury in Virginia convicted former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort on a series of tax- and fraud-related charges uncovered by Special Counsel Robert Mueller during his inquiry. The conviction raised the prospect that Manafort, a key figure in the Trump campaign’s interactions with Russian intermediaries in 2016, would offer evidence to Mueller in exchange for a lighter sentence.

By that time, Trump had already established a pattern of using pardons to reward his political supporters or criticize the Justice Department for its handling of similar cases. Shortly after the Manafort conviction, Trump wrote on Twitter that federal prosecutors “took a 12 year old tax case, among other things, applied tremendous pressure on [Manafort] and, unlike Michael Cohen, he refused to ‘break’—make up stories in order to get a ‘deal.’” Rudy Giuliani, the president’s personal lawyer, told reporters at the same time that Trump wouldn’t issue any pardons until the Russia investigation was complete. As I noted at the time, the signal from Trumpworld could hardly have been clearer: Keep quiet about whatever you might know, and you’ll be rewarded by the boss later.

It’s possible that the White House announced the pardons late on a Friday in an effort to partially bury the politically awkward news, and that Stone’s conviction was merely a coincidence. But it would be hard to fault the president’s former dirty trickster for seeing a clear pattern here or for getting the same signal from Trump that Manafort apparently received last year. The president’s approach to federal investigations, whether into his own misdeeds or those he simply admires, can be boiled down to two simple words: Stop snitching.