What you think of when you hear the phrase “Wounded Knee” depends largely on two factors: how old you are, and whether or not you are Native.

Younger, non-Native individuals may remember Wounded Knee as the topic of a high school history lesson concerning the U.S. Army’s massacre of hundreds at a Lakota camp in 1890. Native people, and older folks who watched the nightly news in 1973, might instead remember it for the twentieth-century armed occupation of Wounded Knee by a group of disaffected Native citizens.

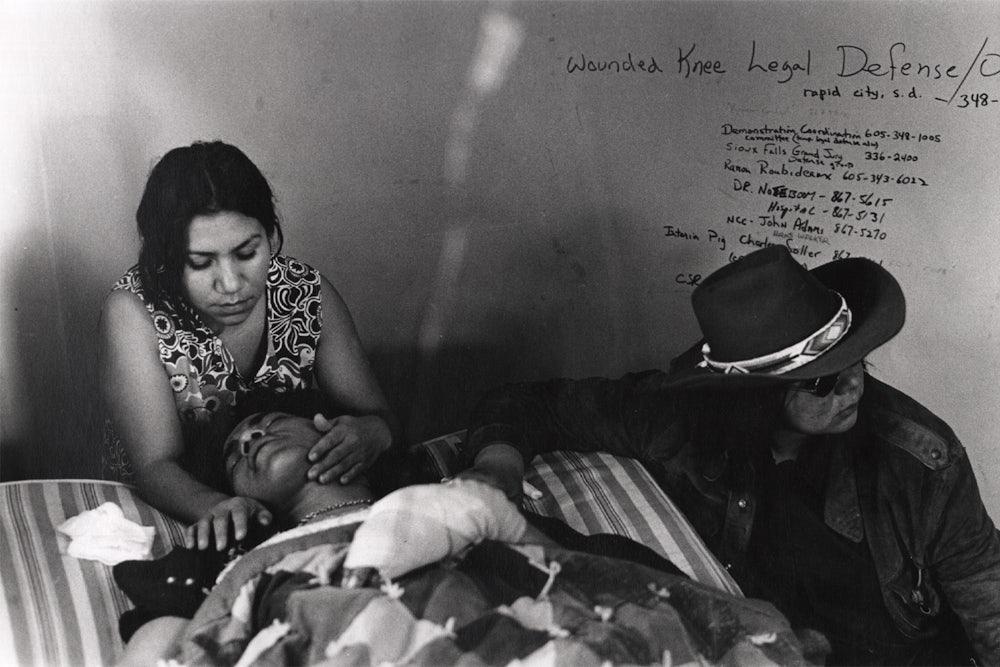

Documentarian and reporter Kevin McKiernan’s latest production, From Wounded Knee to Standing Rock, proposes that there is still more to explore about the historic 1973 civil rights moment. For both the initiated and the ignorant, the documentary dives back into an oft-forgotten moment for non-Natives, methodically examining the American Indian Movement’s motivations for the occupation, as well as the Nixon administration’s responses: a humane but unflinching look at one of the most famous Indigenous resistance groups in modern history, and the questionable decisions made by a president whom many in Indian Country still think of as a hero. McKiernan was the only reporter embedded in Wounded Knee, young and green and hungry when the occupiers were young and green and hungry. Now, 40 years later, with time to reflect on the weight and motivations of their actions, and an unusual comfort in speaking with the person sitting just off-camera, the former leaders and participants are the film’s main draw.

The American Indian Movement, or AIM, was a loosely bound grassroots group that started in the late 1960s as a Native response to the civil rights movement. Leaning on more libertarian values, however, it sought to upend the power imbalance that defined the relationship between the United States and the hundreds of Native nations during the first half of the twentieth century, briefly occupying the D.C. headquarters of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1972. One of the group’s core complaints was U.S. refusal to honor its treaties with Native nations. Co-founders Dennis Banks, Clyde Bellecourt, and Russell Means all make appearances in the documentary, as does Richard Ray Whitman (Yuchi Tribe) and, though not directly, the infamous Leonard Peltier, who is currently serving a life sentence in a supermax Florida penitentiary for allegedly shooting and killing two FBI agents.

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 legally granted the Lakota tens of millions of acres, stretching from Nebraska to North Dakota, including the Black Hills and the Pine Ridge Reservation, on which Wounded Knee was located. When gold was discovered in the Black Hills in the early 1870s, the treaty was violated immediately, the federal government first turning a blind eye to the invading gold rushers and then annexing the territory and creating the Dakotas. But since the treaty, like hundreds of others signed with Native nations, was never invalidated by Congress, it legally maintained its standing.

McKiernan’s documentary opens by discussing AIM’s initial motivation to mobilize around the still-active treaty, but spends more time on the opposition to AIM—both Native and non-Native. The same month AIM began an occupation of Wounded Knee in demonstration against the federal government, an Oglala Lakota civil rights group turned to AIM for help against Oglala Lakota tribal president Dick Wilson, elected in 1972, whose alleged nepotistic governing tactics and makeshift security squad, known as Guardians of the Oglala Nation, or GOON, had alienated many at the Pine Ridge Reservation. The resulting three-party standoff saw Wilson, GOON, and the FBI on one side, and on the other, a handful of armed AIM members with a limited amount of food and ammunition.

The relationship between GOON and the FBI is one of the film’s central preoccupations. In both past and current-day interviews with FBI agents and GOON soldiers who worked at Wounded Knee, McKiernan points over and over to how the tactics they used to undo AIM’s occupation mirrored those used by the CIA in supporting foreign coups. The FBI shot at food pallets delivered to AIM members, as well as at the members themselves; they quietly encouraged Wilson’s local militia force and its power-hungry leader to ostracize AIM and all of its supporters in the local community; they even went so far as to employ subversive Counterintelligence Program, or Cointelpro, tactics to turn AIM leadership against its own members.

Among the many who flocked to Pine Ridge to sneak past FBI lines in the dead of night and join the occupiers was Mikmaq citizen Anna Mae Aquash. Aquash had left her two children with her sister in Boston, writing a letter later explaining why she felt the need to join AIM: “The whole country changed with only a handful of raggedy-ass pilgrims that came over here in the 1500s. And it can take a handful of raggedy-ass Indians to do the same, and I intend to be one of those raggedy-ass Indians.” After AIM relinquished its grip on Wounded Knee, Aquash spent her time organizing schools teaching an honest Native curriculum and took part in another occupation, of an abandoned Catholic center in Wisconsin in 1975. As a result, she was picked up twice by the FBI on weapons charges; both times, she was released shortly after.

In 1976, Aquash’s body was found by a South Dakota rancher as it decomposed in a 30-foot ditch just outside the reservation. While some initially wrote off the body as just another casualty of the occupation—Pine Ridge boasted the highest per capita murder rate in the nation during the armed occupation—rumors started to circulate of an AIM-sanctioned hit.

Aquash’s murder is the focus of the final act of the documentary, in which McKiernan pulls archival footage and interviews a series of surviving AIM leaders criticizing the FBI’s tactics. The federal agents attempted to convince AIM leaders that Aquash was working as a double agent for the U.S. This resulted in three lower-level AIM members—John Graham, Arlo Looking Cloud, and Theda Clarke, who have all since been convicted—driving her off the reservation, executing her via a gunshot to the back of the head, and dumping her body in the ditch.

The documentary leaves viewers to assess the situation for themselves. The responsibility for Aquash’s death belongs to a number of parties. Among the many rumors that have engulfed AIM over the years is that Banks and Means, at the very least, knew about the plan to murder Aquash—former AIM Chairman John Trudell, who is not featured in the film, testified in 2004 that Banks had told him in a private conversation after the body was found by the rancher, but before it was identified, that it was Aquash. In a current-day interview included in the film, McKiernan asks Banks point-blank if he had anything to do with Aquash’s death, to which Banks, after pausing for the briefest of moments, responds, “No.”

Around this time, a line uttered by Ojibwe author David Truer in a recent New Yorker interview reverberated in my mind: “I want better heroes than Russell Means, I want people with more integrity than Dennis Banks. I think we deserve people with more honesty and integrity, I do, there’s too much at stake.”

McKiernan understands his role in the documentary. The story is loosely told from his perspective as a young reporter thrust into a sink-or-swim series of situations at Wounded Knee. McKiernan wrote and provided most of the voice-over, cutting back and forth often with archival news clips and interviews. While, chronologically, Wounded Knee was his first major assignment, as a documentarian, this isn’t his first rodeo. McKiernan also directed the 2000 offering Good Kurds, Bad Kurds: No Friends but the Mountains and the 1990 Frontline feature, The Spirit of Crazy Horse.

A series of crucial questions arise when any such work featuring Native voices and actions is created and sold by a white reporter: What does this work hope to accomplish? Is it the education of non-Natives specifically on the siege of Wounded Knee? Is it an opportunity to center elder, radical Native voices from one of the most famous Indigenous acts of resistance in this nation’s history, as a way of reminding Indian Country of how far it’s come in the time since? And, maybe most importantly, is this form and are these creators the best mode of education?

This is not to question McKiernan’s capabilities as a journalist or a documentarian: He was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 1976 for his 1975 photography work during the firefight that claimed the life of a Native resister and two FBI agents and earned Peltier a spot on death row in Florida. Documentaries produced, written, or directed by white Americans on minority subjects aren’t going to cease anytime soon, even if they’ve already become comedic fodder for the same studios that fund them. McKiernan’s latest offering, like his previous ones, serves as proof that such undertakings can be completed in a respectful, engaging manner and function as a bridge to a wider American history for a non-Native audience, introducing them to material that rarely makes it into most U.S. students’ K-12 curricula.

But this film is also a reminder of the wealth of material awaiting Native reporters, creators, and artists as they continue to reclaim their communities’ stories. There are 573 federally recognized tribes in America, over 100 more state-recognized tribes, and dozens of unrecognized ones. Within them are thousands of stories of resistance, just like Wounded Knee, only without mainstream attention.

McKiernan’s best work in this documentary comes with the delicate humanization of the AIM rank and file. Nowhere is that more true than in the case of Willard Carlson—a guiding voice in the documentary. McKiernan met Carlson, a citizen of the Yurok Tribe, by happenstance, 40 years after Wounded Knee, on a camping trip. Unlike the AIM leaders included in the documentary, Carlson is not present to answer for dubious or fatal intentions; he is here as proof of grassroots empowerment and the outrage toward the U.S. that festered within the dozens of marginalized Native citizens who heeded AIM’s call to action. When he informed his mother in 1972 that he was headed for Pine Ridge, she didn’t try to stop him; she handed over eight rifles.

The film’s most thoughtful shots are saved for the end, when Carlson returns to Wounded Knee. Standing before a memorial, a young Native boy looks up at Carlson. The kid is a bit camera shy, but he musters up the courage to ask Carlson if he was there in 1973. Hearing that he was, the boy regards him with the kind of reverence most Americans reserve for when they spy a lingering World War II veteran. It’s a touching moment, built upon by a series of shots in which McKiernan visits Carlson back home on Yurok land as he establishes Yurok culture for the younger generations. In an era of continuing struggles over land rights, sovereignty, and broken promises, Carlson proves that while it was often obscured by egos and drama, the core mission of Wounded Knee—to strike back at systemic injustice—is still alive and well in the rising generation.