In August, Miguel Medina Cabrera, a Spanish farmer on the island of Gran Canaria in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, watched the land around his farm start to burn.

“The fire was burning for four days, but afterward there were tree trunks that continued burning for fifteen days,” Cabrera told me. “It looked like lava pouring slowly from ten volcanoes. It was very painful to watch, but at the same time it was spectacularly beautiful.”

Cabrera has been putting out wildfires on this island since he was a boy. But he says the number of wildfires has increased noticeably since his youth, and this summer’s was by far one of the worst he has witnessed. That made it particularly frustrating when a far-right party in the Senate temporarily blocked a declaration of support for the victims of the fire, incensed because some senators asserted that the fires might have something to do with climate change.

Climate change is causing an increase in the number of heat waves and large forest fires in Spain, according to researchers from the University of Castilla-La Mancha. Between August 17 and 20, around 10,000 people were evacuated from their homes as two simultaneous wildfires ravaged Gran Canaria, destroying around 25,000 acres of land. Around 90 percent of Gran Canaria is at risk of becoming a desert due to draught and deforestation, according to the Foundation for the Reforestation of the Canary Islands.

“It was like hell. Everything was burning,” Antonio, a local restaurant owner, told me, recalling the recent fire and motioning to the blackened mountains that surround his establishment.

Today, most people have returned home. But the land remains charred and black, and the evergreen trees that top the mountains are turning slowly brown as they die. The smell of ash hangs in the air months after the fire was put out, and the traces of burnt earth show how perilously close people like Antonio came to losing their homes and their livelihoods.

Meanwhile, those who did lose homes and livestock in the fire told me they had to wait months to receive support from the central government and to find out how the government planned to address the environmental degradation. Spain’s socialist Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez visited the island and the military’s emergency unit was deployed to help extinguish the fire. But the far-right party Vox initially blocked an official declaration of support for the victims drafted in the Senate because the statement mentioned climate change. The move, led by a senator from Vox named José Alcaraz, caused uproar, and even members of the right-wing Popular Party denounced the decision.

“Senator Alcaraz, in our opinion, did not demonstrate the sensitivity needed to acknowledge the devotion, sacrifice, and courage of the hundreds of people who played with their lives by working to extinguish the fire,” María Australia Navarro de Paz, leader of the Popular Party of the Canary Islands, told me in October. The Popular Party in Gran Canaria has recently released a proposal for assisting the island with reforestation efforts.

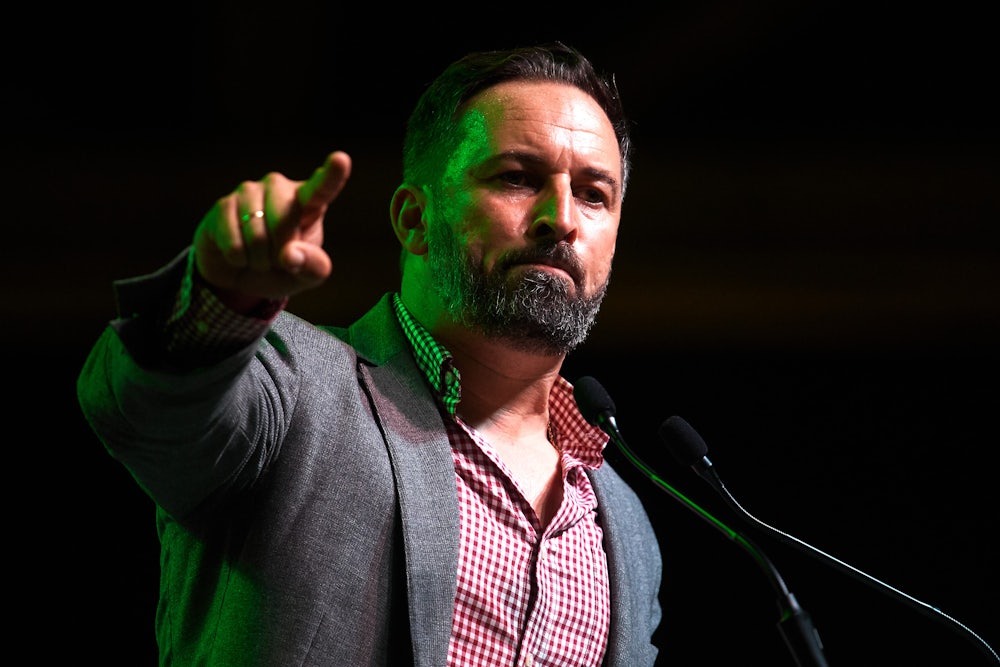

Vox emerged on the scene suddenly in 2018 and won 24 seats in the 350-seat congress. While their primary platform is one of economic liberalism, social conservatism, and anti-multicultuarlism, the party’s leaders also claim that it is arrogant to believe that human activity is responsible for heating the earth’s atmosphere, and have grown increasingly vocal in their global warming denial since this summer’s fires. Vox’s leader, Santiago Abascal, has called anthropogenic climate change a hoax and argued that the government shouldn’t waste money on it. Vox did not respond to requests for comment in time for publication.

“People didn’t used to talk about the issue of climate change very much, but now it’s as salient an issue as feminism,” Luis Cornago Bonal, a political risk analyst with Teneo in London, told me. And like opposition to feminism, climate change denial has become one of the identity-defining features of the far right. Experts warn that far-right parties like Vox could attempt to shift the narrative surrounding climate change to the right at a time when climate action is becoming a more salient political issue in Spain and across Europe.

“Climate change is a new debate in Spain. The country doesn’t even have a Green Party,” explained Kristina Kausch, a Spain-based senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund. “Several leaders of Vox have positioned themselves as climate deniers. They want to frame it as a leftist plot,” she added.

Far-right parties across Europe are increasingly making opposition to climate change a key part of their platforms as groups like Extinction Rebellion, which calls for net zero carbon emissions by 2030, have gained visibility in Europe.

The far-right Finns Party campaigned against climate action and won the second highest number of seats in Finland’s parliamentary elections in April. Leaders of Austria’s far-right Freedom Party, which has representation in the European Parliament, have railed against “climate hysteria” and criticized prominent climate activist Greta Thunberg. And Germany’s anti-immigration Alternative for Deutchland (AFD) party has featured climate change denial and a “save diesel” slogan prominently in recent campaigns. The party made significant gains in elections in the Germany states of Saxony and Brandenburg in September.

The German example is particularly significant, given the country’s leadership on European climate policy, according to Jakob Guhl, a policy and research coordinator at the London-based Institute for Strategic Dialogue. Guhl’s team has tracked the way the AFD increasingly focuses on climate change denial in its online communications campaigns during recent years. “Much of that spike came in the early months of 2019 and relates to the emergence of Greta Thunberg, the face of the school strikes, and of the broader climate movement,” Guhl told me. “It has coincided with a new framing: that accepting climate science is akin to being a member of a cult. Greta in particular has been targeted, with AFD candidates depicting her as a ‘Hitler youth’ and ‘psychotic.’ The AFD uses these narratives to present belief in climate change, and consequently their political opponents, as an irrational, hysterical cult and climate change as a replacement religion.”

Some experts believe the strong presence of the Green Party in the European Parliament could mitigate efforts by the far right to suppress climate policies on a national level. Following elections in late May, the Greens joined progressive regional parties to form a European parliamentary group that controls almost 10 percent of the vote in the increasingly fractured parliament.

“Around 70 percent of the laws that exist in Spain are transposed directly from laws that were defined in the European Parliament,” Luis Torrent Bescós, a Barcelona-based climate change and sustainability consultant, said—an influence that could help check Vox and other far-right parties’ anti-environmentalist policies.

Some have speculated that a newly emerged left-wing party, More Country, could become a sort of Spanish Green Party. But More Country is only projected to win 8 seats in parliament in the upcoming elections in November, and its political platform is just beginning to solidify.

Meanwhile, the right’s impact on climate policy is already being felt. In June, the local government of Madrid swung to the right when the right-wing Popular Party enlisted the support of the far-right Vox and the center-right Citizens’ Party to form a government in the capital. The new government’s first move in office was to roll back environmental protections put in place by Madrid’s previous left-wing government, including scrapping a low emission zone known as Madrid Central. The new mayor, the Popular Party’s José Luis Martínez Almeida, also announced an end to restrictions on the number of cars allowed in certain zones of Madrid.

For residents of the Canary Islands, climate change isn’t an issue of ideology so much as an everyday reality.

“We’re having more and more extreme climate events. The wildfires start almost spontaneously because of high temperatures and high winds,” said Eugenio Reyes Naranjo, an environmental activist and farmer who was evacuated from his home during the fire.

As the risk of wildfires increases, some of the island’s residents wonder whether a government that includes Vox intends to help them—or whether lawmakers will instead spend their time bickering over whether climate change is real.