The name Mark Forkner is by now familiar to even relatively casual followers of the Boeing 737 MAX saga. Forkner is the former chief technical pilot who conducted a series of Grey Goose–addled Skype chats with a colleague about the new 737’s now infamous self-hijacking software MCAS. The supposed piloting-correction device was, Forkner wrote, “running rampant” in the simulator; for good measure, he also noted that he had “lied to the regulators (unknowingly)” about it. These revelations sent Boeing’s stock plunging over news the feds had finally unearthed a “smoking gun” proving the company knew in advance that its badly flawed piece of software could go “crazy” and cause a crash.

Naturally, Boeing pushed back against the headlines, arguing that the chats did not constitute a “smoking gun” because they concerned a pilot operating in a simulator and not behind a real-life cockpit. For once, many of the best chroniclers of the MAX catastrophe agreed with the company.

Still, we should not be led by this fleeting moment of consensus: Most everyone weighing in on the Forkner chats was wrong, or missing the point. At the end of the day, we don’t need a smoking gun to determine exactly what Boeing knew before the first crash, for the simple reason that we saw in real time how company officials responded after the first crash—i.e., with a veritable arsenal of smoking guns in the form of obvious lies and easily contradicted misinformation. This is also the most crucial lesson to fix in mind as Congress renews a round of hearings on the MAX fiasco on Tuesday.

Here’s one extremely revealing diptych from last fall, for example: When Boeing reps were discussing the crash in conference calls and town hall meetings with airlines and commercial pilots in November, they vehemently blamed incompetent pilots, according to a lawsuit from the Southwest Airlines pilots’ union. In talks with the Federal Aviation Administration, however, Boeing advised issuing an emergency directive “reminding” those same pilots of an obscure protocol they might need to employ “in the event of uncommanded nose down trim”—i.e., in case the plane randomly started to nosedive in unprompted fashion.

The original text of the directive contained a damning reference to the now-notorious MCAS system but at the last minute someone removed all references to the software from the directive. This disappearing act was, in turn, an eerie repeat of the program’s mysterious near-total omission from the plane’s official 1,600 page manual.

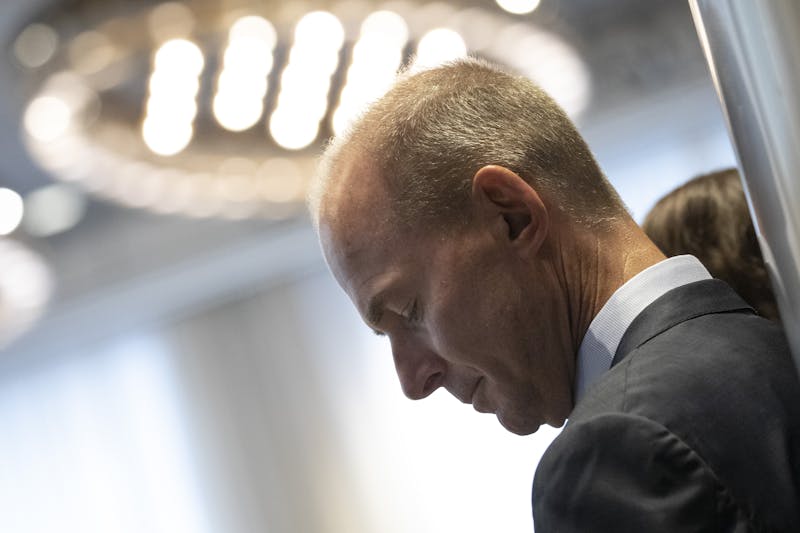

So when prosecutors started digging into the mystery of why the murderous software had been omitted from so much of the official MAX literature and test requirements in early 2019, Boeing handed over the inboxes of Mark Forkner, who had spearheaded certain aspects of the plane’s FAA certification and left the company in rather abrupt fashion a few months before the crashes.

Seen in this context, Forkner’s improbable advancement to center stage in the MCAS narrative is another smoking gun of sorts—that is, once you realize that David Gerger, the attorney he has retained to represent him in the probe, is world famous in white collar criminal defense for being, inter alia, the lawyer who got his client Andy Fastow, Enron’s chief financial officer/debt concealment mastermind, off with a six-year sentence the same year Enron CEO Jeff Skilling got 24. The FBI has interviewed scores of former and current Boeing employees in conjunction with the various investigations into the MAX, but Forkner is the only one known to have retained a criminal attorney. In any event, once you read the chat transcript, it’s abundantly clear that the guy is just about the opposite of Fastow. The chat, which occurred between Forkner and his fellow technical pilot Patrik Gustavsson, took place on November 15, 2017, and happened to coincide with the very moment both pilots learn, via someone named “Vince,” that the MCAS software has been drastically changed from its previous iteration, wherein it operated only at extremely high speeds and existed primarily to enable the plane to properly execute military maneuvers required by the FAA testing regime:

Forkner: Oh shocker alerT!

MCAS is now active down to M .2 It’s running rampant in the sim on me at least that’s what Vince thinks is happening

Gustavsson: Oh great, that means we have to update the speed trim descritption [sic] in vol 2

Forkner: so I basically lied to the regulators (unknowingly)

Gustavsson: it wasnt [sic] a lie, no one told us that was the case

Forkner: Vince is going to get me some spreadsheet table that shows when it’s supposed to kick in. why are we just now hearing about this?

Gustavsson: I don’t know, the test pilots have kept us out of the loop

It’s really only christine that is trying to work with us, but she has been too busy

Forkner: they’re all so damn busy, and getting pressure from the program

“Out of the loop” was an understatement: The MCAS changes, which had the software operating at speeds as low as Mach 0.2 (or about 150 miles per hour), were just the tip of the iceberg. The change in MCAS’s speed capability involved, in fact, a whole host of cascading implications that were hardly self-evident; they’d all been approved nearly a year earlier, and finalized in March—the same month, in other words, that Forkner convinced the FAA to remove mention of the program from the flight manual. Forkner had spent the summer meeting with airlines and regulators easing anxieties about the new plane without any notion that any of this was going on. His one crime appears to have been reiterating his unknowing lie to the FAA once more in early 2017, in the process of confirming the omission of MCAS from the official flight manual. His logic was by then completely obsolesced by events: MCAS didn’t need a manual entry, he argued, because it only ran “well outside the normal operating envelope” of the plane. Indeed, it seems highly doubtful, given Forkner’s self-professed and demonstrated inability to extract information out of his colleagues, that he had any grasp of how MCAS actually worked. That’s especially the case, one can assume, since his colleagues seemed relatively committed to keeping him in the dark about the software and he was busy trying to get the simulator to calm down. Say what you will about previous corporate scandal fall guys; at least Goldman Sachs’s notorious derivatives trader Fabrice Tourre basically understood how a synthetic credit default swap worked. I strongly doubt the same can be said for Mark Forkner and MCAS.

Moreover, lying (especially this brand of regulatory white-lying-by-omission-of-actionable knowledge) to aviation regulators is simply part of staying employed at Boeing. Consider in this regard a recently publicized whistleblower complaint filed internally by current Boeing engineer Curtis Ewbank, who mostly discusses his attempts to equip the MAX with an additional safeguard that arguably could have prevented the crashes, also describes a separate episode in which he was assigned at one point to research in-flight 737 auto-throttle malfunctions following an inquiry from the European Union’s aviation regulator. Ewbank says he was at this point directed to withhold information about the five additional malfunctions he uncovered on grounds that Boeing would “fix it” internally. And yet, for a sin of omission that surely seemed far more benign to someone deliberately unacquainted with the plane’s engineering, Forkner appears to have been Boeing’s designated in-house scapegoat—at least among those who don’t happen to be dead pilots.

More recently, Boeing chairman David Calhoun has also served up a few sackings to quell still-robust calls for change in the company’s culture and business model. The board, with Calhoun as lead director, recently stripped CEO Dennis Muilenburg—one of the few executives at Boeing who still boasts an engineering background—of his chairmanship. (Muilenburg testifies Tuesday before a Senate committee, and Wednesday before a House committee.) Calhoun also sacked David Carbon from his post running Boeing’s notoriously corner-cutting, whistleblower-firing non-union assembly line in South Carolina and canned Kevin McAllister, the commercial aviation chief he recruited to Boeing in November 2016. Like Calhoun, McAllister had spent most of his career at the engine of American deindustrialization and financial engineering that is the General Electric Company; unlike Calhoun, he may have some semblance of a conscience: A week before he was fired, The New York Times published a story claiming five separate sources had told the newspaper that McAllister cried during meetings.

The only specific criticism that his colleagues leveled against McAllister was that he’d presided over “uneven communication” over the MAX crisis. Well, yeah: Communication isn’t Boeing’s strong suit. And it’s not likely it would have gone over well if McAllister or Muilenburg had simply told the airlines, pilots, and victims’ families what Calhoun himself told The Washington Post about the board’s decision not to ground the MAX when it obviously should have, after last spring’s fatal Lion Air crash in Indonesia: “I don’t regret that judgment. And I don’t think we got it wrong at that time and that place.”

While Calhoun’s callous outburst may not technically qualify as a smoking gun, it is hard to think of any better evidence of malign company-wide neglect than the emphatic declaration of a centimillionaire corporate board member that he not only does not regret making a decision that cost 146 additional lives, but that he had also not even been wrong.

Still, I realized something else while scrolling through

Boeing’s last transcript of a company earnings call. During that

investor-reassuring performance, Muilenburg briefly mentioned that the company

had experienced $2.6 billion in negative cash flow during the quarter,

in part because it had spent $1.2 billion sending dividend checks to

shareholders. These checks marked a 20 percent increase

over the same quarter last year, before the two Boeing inflicted MAX crashes

killed 346 people and grounded close to a thousand planes. At a time when

cancelled MAX flights now number in the millions, and MAX-related lawsuits can

be expected to cost the company maybe up to $20 billion dollars,

it’s an odd time indeed to be romancing investors with cash-sweeteners. In

fact, amid the most violent self-inflicted cash crunch in its long history—one

directly caused by a corner-cutting culture that prioritized safety dead last—Boeing is now on track to spend close to $5 billion this year raining

gratuitous money down on shareholders. That is the smoking gun here. That is

all you need to know.

This piece has been updated throughout to correct information about changes made to the MCAS software, as well as the number of people killed in the second 737 MAX crash.