The first thing you notice about Robert Eggers’s sophomore film, The Lighthouse, is not the way it looks, but the way it sounds. Waves, then a foghorn, then wind—they bleed into one another. There’s a score, too, unsettling and anxious, by Mark Korven, but it’s often hard to discern the music from the noise. This is appropriately destabilizing; The Lighthouse means to rile you.

The sound design is an important part of any movie, maybe the more so here because the film itself is so hard to see. Clearly that’s by design. Eggers and cinematographer Jarin Blaschke shot The Lighthouse in a near-square ratio and in black and white. It has the feel of artifact—a period piece, set in the late nineteenth century, that is dead set on being a documentary.

That is obviously impossible. The titular lighthouse is ersatz, built for the production on the coast of Nova Scotia. Still, everything feels real, or at least adheres to our expectations of how that reality looked: wooly sweaters, goofy underwear, sooty faces, bad teeth, dark rooms. Maybe working with history—his first feature, The Witch, was set in Colonial America—allows Eggers access to a time when it was harder to believe the folly that nature could be tamed. Eggers respects and fears nature, both the world around us and the wild within. The roiling waves are some of the most beautiful shots in The Lighthouse, a suggestion that whatever we tell ourselves, nature—human and otherwise—will always win.

The story begins with an apprentice, Ephraim Winslow (Robert Pattinson), arriving on a desolate island in the company of a seasoned keeper, Thomas Wake (Willem Dafoe). As a two-hander it’s closer to Pinter than Shepard, insofar as it’s hard to get a grasp on what, precisely, drives these men into eventual madness (hardly a spoiler; you know it’s coming from the very first shot). Is it isolation? Is it drink? Is it the futility of their task, to conquer the ocean? Do they just not get along or do they desperately want to fuck one another?

If you’re the kind of person who requires a definitive answer, you’re in for a disappointment. If you don’t mind questions instead of answers, you’ll be thrilled.

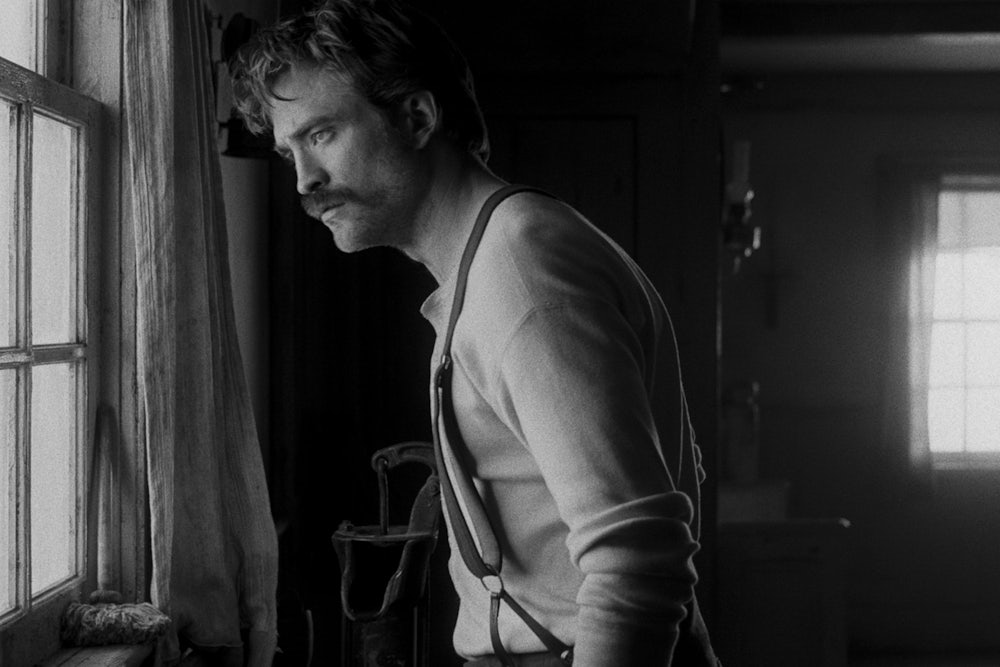

Pattinson is the viewer’s proxy, and god, he is beautiful. Younger, he was more gamine than man, seducing a generation of moviegoers as the conflicted vampire in the adaptations of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight novels. Now in his Jesus year, Pattinson still possesses the sort of beauty that makes him unique even in a business overflowing with pretty faces. Weighing the merits of his performance is subjective; I’m declaring his prettiness objective fact.

His beauty is surely no small part of why directors love Pattinson, particularly the kind of director who yearns for an actor who is at once performer and prop. I’m thinking of David Cronenberg, who cast him as the financial seer in his adaptation of Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis. Pattinson moves through the city in a tricked-out limousine where he fucks, gets a prostate exam, and talks about Rothko, looking unreal in a way that’s sort of horrifying.

Or Claire Denis, who in last year’s High Life gave us Pattinson as a man marooned on the edges of the galaxy. It’s clear Denis adored him, with so many long, loving shots of his face and body. That film made me think of the images Carl Sagan chose to represent the human race on Voyager 1’s golden records, humanity’s long distance call to the cosmos; if you wanted aliens to see the best of us, you could do worse than Pattinson’s visage.

Pattinson’s beauty is a respite in a movie with several arresting visual flourishes—the unruly sea, some menacing birds, the murk of the cistern, the slop the men eat for dinner—that make us queasy. As time passes and the dynamic between the men grows increasingly uneasy, Pattinson is grimy, sweaty, crazed. Still kind of hot, though. Even at his most animal, feverishly masturbating, Pattinson is a lovely animal, a thoroughbred.

I don’t think it’s just that I’m perverted. There’s a palpable sexual dynamic; hell, what is the lighthouse itself but a white phallus towering over all we see?

Dafoe’s Wake—who looks a bit like that splendidly bearded postman Van Gogh painted—is at first gruffly paternal, calling his apprentice “lad” and sternly ordering him to his various tasks. (Dafoe is a Hollywood mainstay but an experimental performer at heart, so however over the top his character’s tongue thrashings and nightly pre-meal prayer are—a maelstrom of archaic verbs and ye olde seafarer-isms—he delivers them with utter conviction.) He is a harsh taskmaster, but Winslow is dutiful. He means to prove himself, even as he’s suspicious of his boss, particularly his refusal to allow him into the sanctum sanctorum, to see the light they’re charged with keeping.

Hard as Wake is on his charge, he allows that he is “pretty as a picture.” There’s a sub/dom thing happening. Just so we’re clear, Winslow at one point wishes he had a steak—not so he could eat it, but so he could fuck it.

The two don’t fall into bed, but they do fall into one another’s arms, slow-dancing drunkenly after a storm prevents the arrival of the boat meant to relieve them. Things then truly fall apart. The descent into violence feels inevitable, but what transpires is still surprising. In this film, as in The Witch, Eggers is playing with the tropes of horror, but we’re so used to those deployed as sleight of hand that it’s a shock when the horror doesn’t try to hide itself. In the first film, the girl accused of being a witch ends up, well, being a witch.

The Lighthouse offers less clarity. Once again, Eggers gives viewers what we want and what we’re sure we won’t get: a look inside the lighthouse. What we find there is both a disappointment and in excess of our expectations.