On April 19, 2019, a man—who, in his profile picture, wears a hat emblazoned with the Confederate battle flag—posted in a Facebook group called “Black Confederates and Other Minorities in the War of Northern Aggression,” which has more than 2,000 members. “Heads up y’all there’s gonna be a book coming out in sept saying black confederates are a myth,” he wrote. “Be prepared to give a negative review on amazon when it’s released.” “I damned sure will,” another man immediately replied.

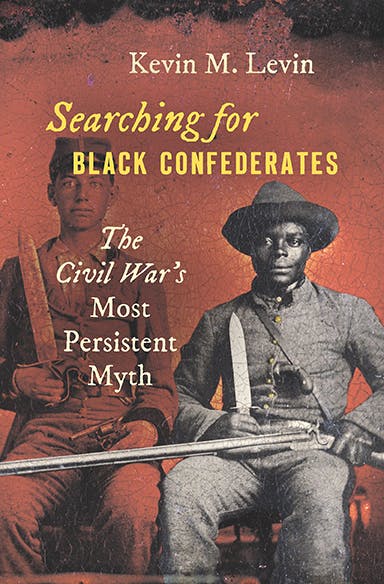

Within this online community, the publication of Kevin M. Levin’s excellent book, Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth, is nothing less than a declaration of war. In the last several decades, Levin writes, a growing number of people have begun to accept as fact claims that between 500 and 100,000 black soldiers fought in racially integrated units in the Confederate Army. There are hundreds of web sites, legions of online communities, and whole books devoted to perpetuating these claims. Billboards reading “75,000 Confederates of color?” have recently appeared in Missouri, and one fourth-grade Virginia history textbook asserted that “thousands of Southern blacks fought in Confederate ranks.” Although it is difficult to measure the pervasiveness of this narrative, one study from 2013 found that 16 percent of students at a Virginia university believed that “blacks fought for the Confederacy.”

Yet, as Levin patiently explains, this is totally untrue—predicated on a misreading and misunderstanding of historical documents, as well as outright lies and manipulations. The myth of black Confederates enables white supremacists to portray the Civil War inaccurately as a struggle over states’ rights, not slavery; as a fight for Southern liberty, not for oppression. This in turn justifies their retrograde and racist politics in the present. To those who have embraced this myth, Levin’s book is a terrifying prospect, and for good reason. Searching for Black Confederates is a bracing corrective, a slender yet vital volume in the growing library of texts dedicated to dispelling white supremacist talking points.

There were plenty of black men present in Confederate Army camps, and even on the gray side of Civil War battlefields. The Confederate Army pressed tens of thousands of slaves into work as teamsters, butchers, blacksmiths, ditchdiggers, and hospital attendants; thousands more were brought to war by their masters, for whom they performed less desirable labor and assisted with washing, sewing, and food preparation. Countless slaves used the excitement of war and the confusion of battle to flee. Many others stayed, some for years, sometimes even saving their masters’ lives and nursing their wounds; they may have felt some sense of kinship with their masters, with whom they were now sharing close quarters and the intimacy of the trenches, but many undoubtedly remained because they had family still on their masters’ homesteads, and they feared reprisals against their loved ones or the loss of the chance to reunite. As the war continued, the increasing flood of escapes led the Confederate Army to employ free blacks—“who, it was believed, had fewer reasons to flee”—though only in “support roles.”

It is true that some black men did occasionally “man artillery and perform as sharpshooters,” likely when they themselves feared Northern shells or after their masters had fallen. But these black men were not soldiers. Indeed, they could not have been. The Confederacy did not allow black men—free or enslaved—to serve in its military. As the Confederate Army began racking up defeats, there were increasing calls to dragoon slaves or pay free blacks to serve as soldiers, and Jefferson Davis eventually voiced his support for this—but it never came to pass. Lee surrendered before a single black Confederate soldier ever marched into battle.

Observers at the time vehemently denied scattered reports in Northern newspapers that the Confederacy had recruited black soldiers. “This is utterly untrue,” wrote John B. Jones of the Confederate War Department. Even the few black men who tried to fight for the Confederacy were ultimately blocked from doing so. Though free men of color formed the 1st Louisiana Native Guard in 1861, the law limited membership in the state militia to “free white males,” and the unit “was never accepted into Confederate service.” By September 1862, many of its former members were fighting for the Union.

In the years immediately following the war, no reports or memoirs emerged of black Confederates. Such accounts would have struck former Confederates as bizarre or absurd—and certainly demeaning to white supremacy. As the so-called Lost Cause narrative began to take shape, stories of camp slaves being rebellious or lazy were forgotten, replaced by magnolia-scented tales of loyal slaves who were only too happy to serve the Confederacy (in noncombatant roles). Statues and monuments were erected to celebrate Dixie, some of them depicting adoring blacks—though none of them in uniform.

It was only in the 1970s that the myth of black Confederate soldiers emerged. This was an era in which scholars reevaluated slavery and its role in causing the Civil War, teachers challenged the Lost Cause hagiography so predominant in museums and textbooks, and civil rights activists battled white supremacy in the streets and in the courts. In popular culture, the role that black people themselves, especially black Union soldiers, had taken in destroying slavery became increasingly visible. Alex Haley’s wildly popular Roots television series, released in 1977, enraged the neo-Confederate community, as it portrayed the long genealogy of black resistance to slavery; the 1989 movie Glory, depicting the heroic black men of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, and Ken Burns’s 1990 Civil War PBS miniseries angered them, too.

A group called the Sons of Confederate Veterans began pushing back, fighting for the Lost Cause legend—and, in so doing, they created the myth of black Confederate soldiers. First through articles in Confederate Veteran magazine, SCV leaders began arguing that Confederates had been fighting for the freedom of the South and against Yankee interlopers, not for slavery or white supremacy. To lend credence to this pretense, they began claiming the existence of “black veterans,” digging up photos of slaves in Confederate regalia and records of black people receiving Confederate military pensions as evidence that black men had served as Southern soldiers. Levin devotes an entire chapter to showing that the “exceedingly small” number of black men who received such pensions received them as former slaves or servants, never as soldiers.

More recently, the SCV has begun placing “Black Confederate” markers on the graves of black men, in an effort to “literally inscribe its preferred interpretation of the role of African Americans in the Confederacy at their final resting places.” These ceremonies are often elaborate and well-publicized events, designed to make a statement rather than quietly show respect. With the advent of the internet, neo-Confederates also created thousands of web sites “to spread their understanding of the war beyond the confines of their narrow community.” Many of the sites feature primary sources, lending them a sheen of credibility, but the materials have “either been misinterpreted or even manipulated.”

A small number of black people have embraced the myth, speaking at reenactments and other Confederate heritage events. Their presence is a conundrum that Levin could have devoted more time to plumbing. He proposes that “a small number of African Americans have embraced the black Confederate narrative as a means to identify and to celebrate stories of ancestors who they believe have been long forgotten or intentionally ignored.” He also speculates that the myth may have “offered conservative black Americans an outlet to voice their political agenda.” Interviews could have rounded out these observations, and could have proved worthwhile, too, in Levin’s discussion of SCV activities, though he has gotten his hands on some internal SCV reports.

Levin seems more in his element when challenging prominent academics, such as John Stauffer and Henry Louis Gates Jr., who, he writes, have misinterpreted evidence and spread “unsubstantiated claims about the existence of loyal black soldiers,” despite never having “conducted any serious research on this subject.” Stauffer has discussed it in his university lectures for years, and in an essay in The Root (which has been gleefully cited by neo-Confederates), while Gates has spread the myth on his PBS show Finding Your Roots, among other places. Gates has also publicly claimed that scholars’ refusal to embrace the black Confederate narrative is evidence of “left-of-center” academics censoring themselves and ignoring the “complexity of the African American community.”

The myth of black Confederate soldiers is important because it allows neo-Confederates to manipulate the popular understanding of white supremacy; to claim that flying the Stars and Bars is a matter of heritage, not hate. Levin notes that during the campaign to remove the Confederate battle flag from state grounds across the South following the murders at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015, the SCV objected. Its argument for keeping the flag cited the existence of black Southern soldiers. Happily, the neo-Confederates lost that fight. With this important book, Levin is determined to rout them once and for all.