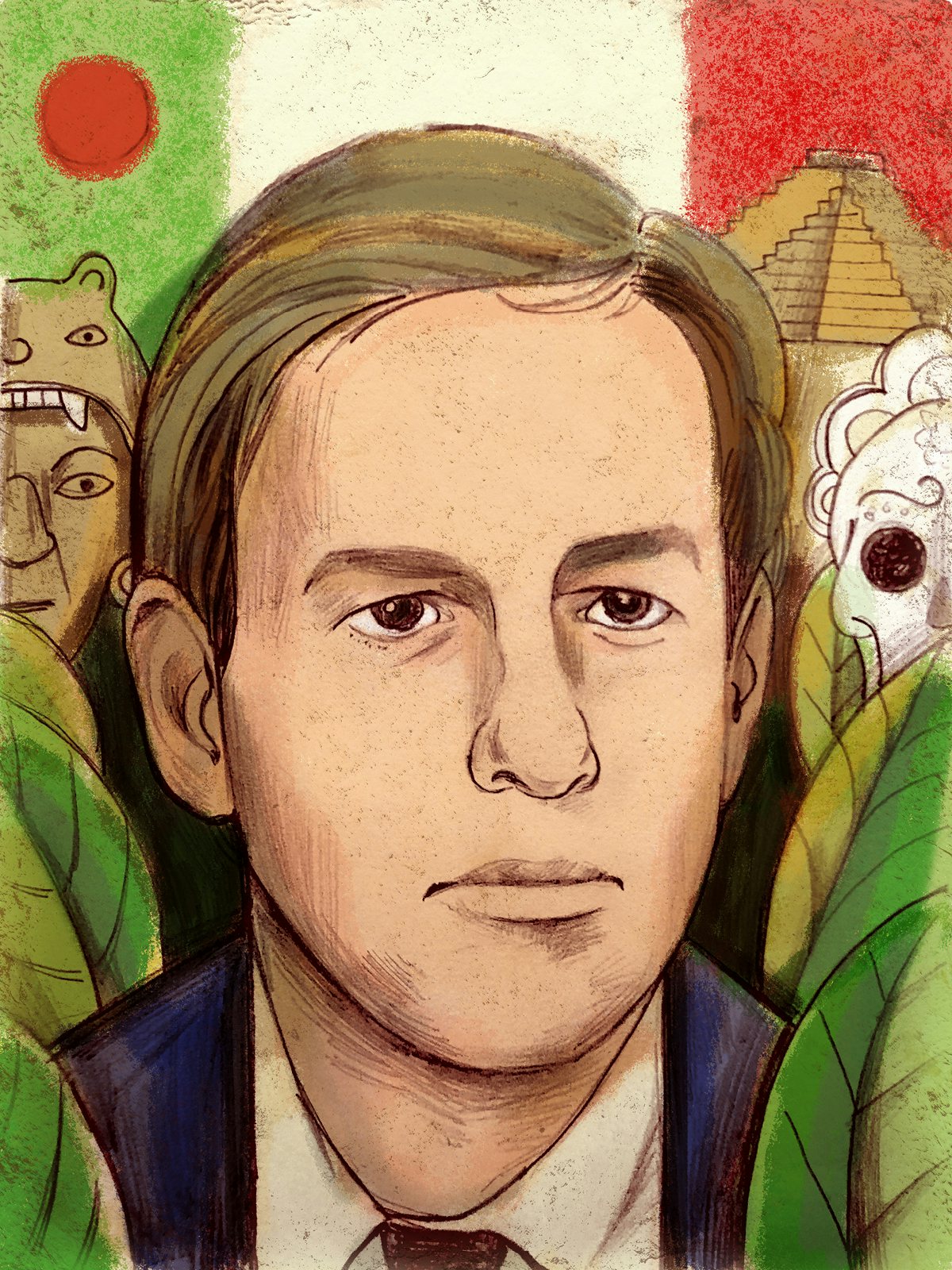

There is a type of conservative who constantly clamors for war, who believes corporations and the men who run them are benevolent, who equates the cause of freedom with Western domination over the wretched of the earth, and whose every word and gesture is meant to perform a kind of late Victorian chauvinistic masculinity. This sort of conservative, while increasingly out of step with the vulgar populism of Donald Trump’s Republican Party, continues to enjoy pride of place in this country’s elite institutions. And there is no better example than our era’s most infamous bedbug: New York Times columnist Bret Stephens.

Stephens, of course, is not actually a bedbug, even though he was called one on Twitter by a once-obscure professor named David Karpf. Quite the opposite: Stephens holds one of the most influential and least accountable jobs in media—a position he’s so far used to dissemble about climate change, to defend Woody Allen’s character, to repeatedly misrepresent the outcome of last year’s midterms, to push for war against Iran, and to compare Karpf to Joseph Goebbels after failing to get him fired over his bedbug tweet.

That last incident, in which Stephens smuggled a petty subtweet into the paper of record in a column ostensibly commemorating the 80th anniversary of the Nazi invasion of Poland, marked an embarrassing low point in the tenure of James Bennet, the Times’ opinion editor. Two years ago, Bennet brought Stephens on from the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal, one of the last bastions of Laffer curve–loving, poor-shaming conservatism in the journalistic mainstream. As his profile rose, I started to wonder: Where, exactly, did Stephens come from? Who made him like this? What is the root of the haughty aristocratic conservatism the Times chooses to foist on its liberal readership twice a week?

As it turns out, Stephens’s background contains more than a few tantalizing clues. It’s an international epic, filled with sex and violence (you’ll see). It’s the story of a fascinating and unlikely family buffeted by wars and revolutions and avant-garde artistic movements—all of which somehow culminates in the matriculation of a privileged son to the elite ranks of opinion-making.

A few months ago, Stephens wrote that “ordinary” Americans are bothered by people who speak Spanish. Unsurprisingly, this set off an angry Twitter mob, to which Stephens responded by tweeting, “Fwiw, my late father was from Mexico. My mother was a refugee. I grew up in the D.F. [Distrito Federal, a common shorthand for Mexico City] I speak Spanish [...]” While none of that explains why Stephens felt the need to ventriloquize “ordinary” Americans and invest them with xenophobic views, it’s nonetheless helpful context. To understand where Stephens is coming from, you have to know a little bit about Mexico.

In the 1930s, Mexico was in the midst of a political and cultural renaissance under the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas, who enacted a suite of policies based on the radical ideals of the Mexican Revolution—redistributing land, advancing the rights of women and indigenous peoples, and nationalizing the oil industry. (This latter move punctuated a long interval of conflict over control of the country’s petroleum reserves that had forced a wealthy American oilman and Catholic counter-revolutionary out of Mexico in 1921; many years later, that oilman’s son, William F. Buckley, Jr., would become an inspiration to Bret Stephens.) This was also the heyday of the great socialist realist muralists Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Siqueiros, who had been pioneering a new post-revolutionary aesthetic for the Mexican state since the 1920s. It was Rivera who would persuade Cárdenas to offer Leon Trotsky asylum in Mexico City. Trotsky, in turn, would carry on an affair with Rivera’s wife, Frida Kahlo, before he was murdered by Stalinists in his own home in the bohemian neighborhood of Coyoacán in 1940.

This was the social world of Stephens’s paternal grandparents, both of whom grew up in New York and settled in Mexico City in the Cárdenas years, albeit for very different reasons. Bret’s (for clarity’s sake, I will refer to him by his first name from now on) grandmother was one of the many under-appreciated women artists of the 20th century.

Annette Nancarrow, née Margolis, grew up in a comfortable Manhattan family. Her father ran a business, dabbled in theater, and

socialized with intellectual luminaries like Sinclair Lewis, John Dos Passos,

Theodore Dreiser, H.L. Mencken, and Nation

editor Oswald Garrison Villard. She attended

Hunter College, where she showed early promise as a painter, along with a knack

for flouting social conventions. She went on to earn an MFA at Columbia,

and her fascination with the leading Mexican

muralists of the era led to a family trip to Mexico City in 1935. It was there that

the 28-year-old Annette, who had been raising a daughter with a white-shoe

lawyer on Riverside Drive, met Louis Earle Stephens.

Stephens, born Louis Ehrlich in Kishinev (then tsarist Russia, now Moldova) in 1901, fled with his family in the wake of an especially vicious pogrom. In New York, where he adopted the surname of the Irish poet James Stephens, he worked in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and found success in the textile industry. Eventually he made his way to Mexico City, where he founded a chemical company called General Products and built his fortune. In 1935, connected by a mutual acquaintance, he showed Annette and her husband around his adopted hometown. Annette was smitten, both with Mexico and with Louis. Annette soon arranged a return visit to Mexico, “to test our physical compatibility,” as she later put it in a letter to a German academic in 1991. Upon arrival in the port of Veracruz, she and her sister were attacked by—I swear I’m not making this up—bedbugs (at least, according to one colorful online biography).

“Katy” and “Stevie,” as Annette and Louis called each other, had an intensely passionate affair. “My life with Stevie was very exciting,” Annette later wrote. “We had an ardent relationship; he exceeded my wildest dreams as his inexhaustible energy and variations on the mating theme.” Before long, Annette had divorced her husband—not so easy in the 1930s, and at the cost of being separated from her daughter—and settled in Mexico City, where she and Louis enjoyed what sound like some extremely fun years. They raised two sons, Charles and Luis, painted, designed jewelry, played jai alai, and attended bullfights. They socialized with Rivera (who painted a muscular Louis shirtless) and Kahlo (a devoted fan of Annette’s art, which shows the clear influence of Picasso, Gauguin, and the Mexican muralists) and Trotsky (albeit only briefly). They entertained these and other notable guests at their magnificent home in Tlacopac, which is now an international artist residency. Annette would later recall dressing up in traditional Mexican costumes and hats with Rivera and Kahlo and “hamming it up.”

But their bliss was

not to last. After Pearl Harbor, 41-year-old

Louis insisted on returning to Brooklyn to enlist in the U.S. Navy and left an

enraged Annette in Mexico City with the kids. Louis was a patriot, an avowed

fan of Winston Churchill, and a conservative to his core, and there was no way

he was going to wait out World War II with a bunch of artists in Tlacopac.

A few months after Louis shipped out to fight the Japanese, Annette struck up an affair with Conlon Nancarrow, a brilliant Arkansas-born composer, marijuana enthusiast, socialist, and recovering Stalinist who had volunteered in the Spanish Civil War and was later exiled to Mexico, where his work would only become well known many decades later. Annette’s marriage with Louis fell apart after the war, and she ended up wedding Nancarrow and taking his surname. Although she would have one more husband after that, Annette Nancarrow remains the name by which she is best known. The rest of her life—in which she received an award for one of her murals from the president of Mexico, mingled with celebrity refugees from McCarthyist Hollywood in Acapulco, and eventually split her final years between Mexico City and New York—is well worth reading about. Annette represents one set of values her grandson might have embraced.

So to summarize: Bret Stephens’s grandfather—a captain of industry, a Navy man, a staunch conservative—was cuckolded by a leftist composer while he was off fighting in the Pacific. It’s tempting to get Freudian about the origin of Bret’s politics, and that’s a temptation I ought to avoid, except, well, Bret himself said the following, in his 2011 eulogy for his father Charles:

He was literally born into the ideological feuds of the 20th century. My grandmother Annette was an acquaintance of Leon Trotsky, a friend of Anais Nin and Diego Rivera. Her third husband was the communist composer Conlon Nancarrow. My grandfather Stevie worshipped Winston Churchill, believed in free enterprise and a strong defense, hated communism. My grandparents divorced when my father was eight, and you could say my father wasn’t neutral between his parents’ points of view.

You could indeed say that. Charles, born in 1937 in Mexico but raised in Los Angeles after his parents’ divorce, was, at least to hear Bret tell it, “a real macho man” and a classic Cold Warrior. He visited the USSR in the 1950s intending to pass out copies of George Orwell’s 1984 (he did not end up going through with this plan). In 1970, Charles organized the Youth Committee for Peace With Freedom and led 100 young people to Washington to demand the Nixon administration continue to bomb Southeast Asia. Again, to quote Bret from his eulogy:

In the late 1960s [Charles] became one of the very few people to actually protest in favor of the Vietnam War. Now that took self-confidence. As a graduate student at UCLA he got the Students for a Democratic Society kicked out after they tore down some of his posters depicting Vietcong atrocities.

(Just as a side note

here, leftists have apparently been fighting with the Stephens men over free

speech on college campuses for half a century. But I digress.)

He met Richard Nixon in the Oval Office and advised him to mine Haiphong Harbor and resume the bombing of North Vietnam—which in fact is exactly what Nixon wound up doing. He campaigned for Congress in 1974 on a platform opposing the decriminalization of pot and supporting the government of South Vietnam.

As this panegyric suggests, Charles’s political

career in the United States was dead on arrival. Soon enough he returned

to Mexico City, along with his wife Xenia and their newborn son Bret, to help his brother run the chemical company they inherited.

(Xenia, I’ll pause to note, was born in Italy in 1940 to a refugee who had fled

from the Bolsheviks in Moscow and from Hitler in Berlin; she survived a

childhood under Mussolini before emigrating to the U.S. at age 10, and her

experience recently moved Bret to stand up for refugees against the Trump

administration’s draconian policies, which is entirely to his credit.)

While managing General Products, Charles

also developed a side gig penning fiery

anti-communist op-eds for the English-language newspaper there. (At least one

of these broadsides was reprinted in Human Events, Ronald Reagan’s favorite publication, which supported apartheid in South Africa and also

published such luminaries as Ann Coulter, Pat Buchanan, and Newt Gingrich.)

Stephens credits his father with inspiring his own career in journalism.

“That’s how I learned what an editorial page was; that’s how I learned how to

turn a phrase; that’s how I learned to place a political argument in a

historical context and a philosophical frame,” he said of his father’s

newspaper days, adding, “To this day, every column I write is written with my

dad’s voice sounding in my ears.”

Bret waves away his father’s inherited privilege. “I sometimes suspect that some people who knew my father only superficially thought that his entire life came down to good luck: First-born son, born to a wealthy father, naturally good looking, that kind of thing,” Bret said of Charles. But, he added, “The truth of my father’s life is that the good things that happened to him happened mainly on account of the choices he made. The wealth he leaves behind isn’t the wealth he inherited ... My dad made his own luck.” Not to begrudge anyone a bit of hyperbole in the context of mourning a parent, but this is the sort of phony rugged individualist myth one embraces when, for instance, trying to defend the Trump tax cut while complaining that it “barely cuts the top income-tax rate.”

Conservative pundit tropes weren’t the only thing young Bret absorbed while growing up in Mexico City. Speaking at an interfaith conference in Jerusalem in 2003, Bret recalled being raised by secular Jewish parents and receiving no religious education or Bar Mitzvah, but nonetheless confronting “a hostile environment for Jews.” This, at least, was how Bret justified what to me reads as contempt for the vast majority of Mexicans. According to Israel Insider, “Stephens saw Catholicism as practiced in Mexico with its heavy pagan influences as ‘primitive.’” He changed his mind when he left Mexico for university and met American Christians.

“It was a revelation to me that you could be a sincere Christian and not be a peasant,” he said. According to Israel Insider, “As he became more committed to Israel, it was hard not to notice [...] that it was Christian conservatives who were amongst the most supportive of Israel.”

In other words, Bret came around on Christians after he met some who were white (and pro-Israel). But while Bret’s views on Christianity may have evolved, his subsequent publicly expressed opinions of Arabs and Muslims seem to echo his earlier attitude toward the “primitive” Mexican “peasants.”

Bret spent most of the first 14 years of his life in Mexico, but then attended an elite boarding school in Massachusetts, followed by the University of Chicago. He initially hoped to major in anthropology (he wanted to be Indiana Jones) but found his first course in the discipline “kind of grim and political and tedious.” He therefore opted for political philosophy, which allowed him to stay comfortably within the Western canon under the mentorship of the neoconservative scholar Leon Kass, who would eventually become known for advising George W. Bush to ban stem-cell research.

Although Bret would later claim that “what I really wanted to do was go to officer candidate school and be a Naval officer” as his grandfather had, it turned out that he had high blood pressure. So instead, immediately following graduation, Bret went to work at Commentary before earning an M.A. from the London School of Economics. He then joined The Wall Street Journal as an op-ed editor at 25, moved to Brussels to cover the European Union, and was appointed editor-in-chief of The Jerusalem Post at 28, just months after the 9/11 attacks. “One of the reasons I left The Wall Street Journal for The Post was because I felt the Western media was getting the story wrong,” Bret later told the UJA-Federation of Greater Toronto. “I do not think Israel is the aggressor here. Insofar as getting the story right helps Israel, I guess you could say I’m trying to help Israel.” While in Jerusalem, he enthusiastically championed the Bush administration’s war on terror and the invasion of Iraq, and in 2003 he named Paul Wolfowitz the Post’s Man of the Year.

In 2004 Bret returned to the Journal, where he was eventually promoted to deputy editorial page editor, and where he won the Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 2013, the same year he wrote a column comparing Palestinians to mosquitos. In 2017, newly appointed New York Times opinion editor James Bennet made Bret—by this point among the most prominent of the small handful of “Never Trump” conservatives—his first hire. And you know the rest.

In 2016, The New York Times listed Mexico City as its #1 travel destination in the world, dubbing it “a metropolis that has it all.” It was an overdue choice; Mexico’s capital, which had long been written off by a certain kind of tourist as polluted, dangerous, and sprawling, is in fact one of the most sophisticated cities on earth for visual arts, historic architecture, and fine dining, and is finally being recognized as such in the U.S. Annette Nancarrow was way ahead of her time in this regard.

You can learn a lot in Mexico City. You can see the world’s largest collection of Meso-American art at the National Anthropology Museum; the excavated Aztec ruins of the Templo Mayor; the explicitly Marxist murals of Diego Rivera at the heart of the National Palace; the charming Casa Azul where Frida Kahlo lived, and the bullet-ridden home of Trotsky a few blocks away. You can see great wealth and great poverty, and you can meditate on why the latter always seems to accompany the former. You can attempt to reckon with a genocidal crime that began five centuries ago and never really ended. And if your family had a personal connection to the Mexican ruling class, you might feel it incumbent upon yourself to do so.

Or you can learn different lessons. You can learn, for instance, that society should operate according to a rigid social caste system, in which business and artistic elites intermingle in lavish homes while dismissing and fearing the rabble outside the gates. You can learn to be from a place without really being of it, to take pride in the cachet of having lived there while spending your adult life in a series of very rarified, very white, and very gringo institutions. You can learn to identify instead with the Israelis as they dominate and colonize the land where their perceived inferiors have lived for centuries. Once you’ve absorbed all of that, a lifetime tenure at the most powerful op-ed page on earth awaits you.