The story by now is near-common knowledge: In the throes of the last recession, the nation’s Big Three automakers—General Motors, Chrysler, and Ford—accepted a $51 billion bailout from the federal government, allowing the companies to stave off bankruptcy and eventually recover to reap profits by the fistful. American taxpayers, meanwhile, lost $11.2 billion on this investment by the time the government sold back its bailout shares.

In the years that followed, the massive investment and the discussion of whether the government should have stepped in to help the flagging companies dominated national coverage of the deal. But, as was the case with the financial industry bailout, it was the story of what happened to the little guy—in this case, the autoworkers—that was always shuffled off to the side. Until this week.

Before the Recession hit, GM was already in a bad spot. In 2005, the company shuttered portions of a dozen facilities and laid off 30,000 people. Two years later, in October 2007, United Auto Workers, the union representing the majority of the sector’s labor force, signed a contract with GM that drove a wedge through the heart of its rank and file. The labor agreement established a two-tier pay-rate system that locked in lower salaries for those deemed to be working “non-core” jobs. The contract also swapped pensions with 401ks for new hires, put an end to cost of living wage increases, and implemented a four-year wage freeze and a hefty 3 percent health care cost-sharing requirement.

The 2007 contract dispute spurred a brief two-day strike and later protests. Ultimately, the agreement was ratified. The prevailing idea at the time was that the workers would sacrifice, with the assurance that the company would do right by them once it was able to achieve financial stability. Yet, come June 2008, with the financial collapse dragging the economy into recession, GM announced it would close four plants and cut 10,000 jobs. By December, the company, on the brink of bankruptcy, leaned on the government for a lifeline.

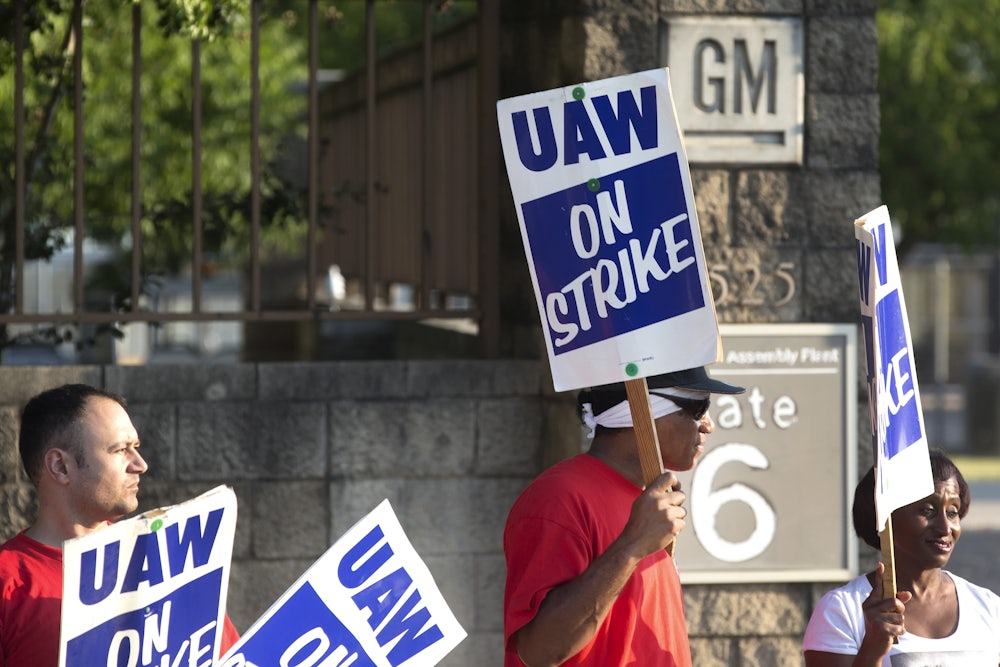

Over a decade removed from the crisis, GM is in the black thanks in no small part to American taxpayers and the company’s own workers. But rather than pay back its workforce for their sacrifices with a fair contract, the company waited until the current contract was on the brink of expiring to offer a deal that would only further squeeze the workers. Because of that, 46,000 UAW members across the nation are on strike, and with so much of the contract left to negotiate, the union is bracing for a lengthy fight.

The biggest sticking point is that the proposal from GM fails to provide a clear path to full-time employment for temporary workers, who make up 7 percent of its workforce; the offer also does not increase wages for what are known as “in-progression” workers. Since the recession, GM has argued that it needs the temporary employees to fill in for full-time workers out on sick leave or vacation. The company has instead used these workers on a more regular basis, allowing it to cut down on its healthcare and benefits costs.

The proposed contract also does not provide adequate protection for employees in GM’s remaining 55 facilities. In November 2018, GM announced it would be shuttering four plants in the near future, leaving roughly 14,000 workers and numerous communities out in the cold. As Sarah Jaffe outlined for The New Republic in June, the closure of the sprawling Lordstown, Ohio, factory is expected to send shockwaves rumbling throughout its community as workers pack up and leave for wherever it is that jobs remain. (At the time of the 2007 strike, UAW represented 73,000 GM workers; today, that number is around 46,000.)

But avoiding another bad contract is not the UAW’s most pressing issue. As the union dives into tense contract negotiations, its leadership is crumbling thanks to a series of bribery and embezzlement scandals that have left many workers wondering who they can trust. A federal criminal complaint claims that the union heads have been routinely using member fees to pay for personal luxuries, ranging from high-end salons to golf trips to shopping sprees. The most recent arrest came last Thursday, when police took UAW Region 5 director Vance Pearson into custody on six charges, including the embezzlement of union money and money laundering. This followed a raid on the house of UAW president Gary Jones, who, though not at this point charged with a crime, is included in the federal complaint, and the convictions of nine others, including UAW administrative assistant Michael Grimes.

Much of the issue is wrapped up in those fraught 2007 negotiations. It was then that UAW leadership agreed to forgo its retirees’ health funds in exchange for stock in the Big Three auto companies and a seat on GM’s board of directors. While this proved to be a sound financial investment within eight years, it naturally entwined the concerns of union leadership with those of the company stockholders. Then, in February 2018, the UAW lost its seat on the board when the trust sold 40 million shares in GM for $1.6 billion, dropping the union below the 50 percent threshold of shares necessary to hold on to its seat.

The scandal could not have come at a worse time for the union. Going into negotiations with GM, when solidarity among the ranks and trust in the leadership is needed most, there is instead doubt and trepidation about whether those on the workers’ side of the bargaining table have employees’ best interests in mind. More distressingly, it has left the UAW with little opportunity to root out corruption from the top down. The end result has been a spate of protests by small groups of auto workers, with no solid anti-corruption proposals from the leadership of the union’s international parent organization.

Small group of @UAW members and supporters protesting against union corruption and voicing support for union reform ahead of the parade starting. pic.twitter.com/lKGBUf7nXk

— Michael Wayland (@MikeWayland) September 2, 2019

As of Tuesday, a slew of local and national Democratic Party politicians have voiced support for the striking union workers. The top three presidential candidates—former Vice President Joe Biden and Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders—have all thrown their weight behind the UAW. Meanwhile, Donald Trump, the 2016 presidential of choice for many in the South and the Rust Belt—where the majority of the GM plants are located—has repeatedly sidestepped the issue. He first posted a message to Twitter on Sunday that called on the two sides to “get together and make a deal!” On Monday, Trump dodged a question about the strike, refusing to openly support union workers.

“Nobody’s been better to the autoworkers than me,” Trump said. “I’d like to see it work out but I don’t want General Motors building plants in China and Mexico.... I don’t want these big massive auto plants built in other countries and I don’t think they’ll be doing that anymore.”

Trump added that his “relationship has been very powerful with the autoworkers, not necessarily the top [UAW] person or two but the people that work doing automobiles.”

The truth of the workers’ situation is not a pleasant one: They cannot expect GM to offer them a fair contract—one that recognizes and repays employees for their prior concessions. Pending a full investigation of corruption allegations, it appears they cannot depend on the UAW to protect and invest their dues without skimming off the top. And they certainly can’t depend on a federal government run by an administration that has a habit of picking anti-union apparatchiks for Labor secretary, ones who consistently favor business interests over workers.

Yet amidst that dim reality, the fact remains that GM would have been among the last recession’s biggest victims without concessions from rank and file. Management knows it, the union knows it, and boy do the workers know it. Empty promises lead to empty factories.