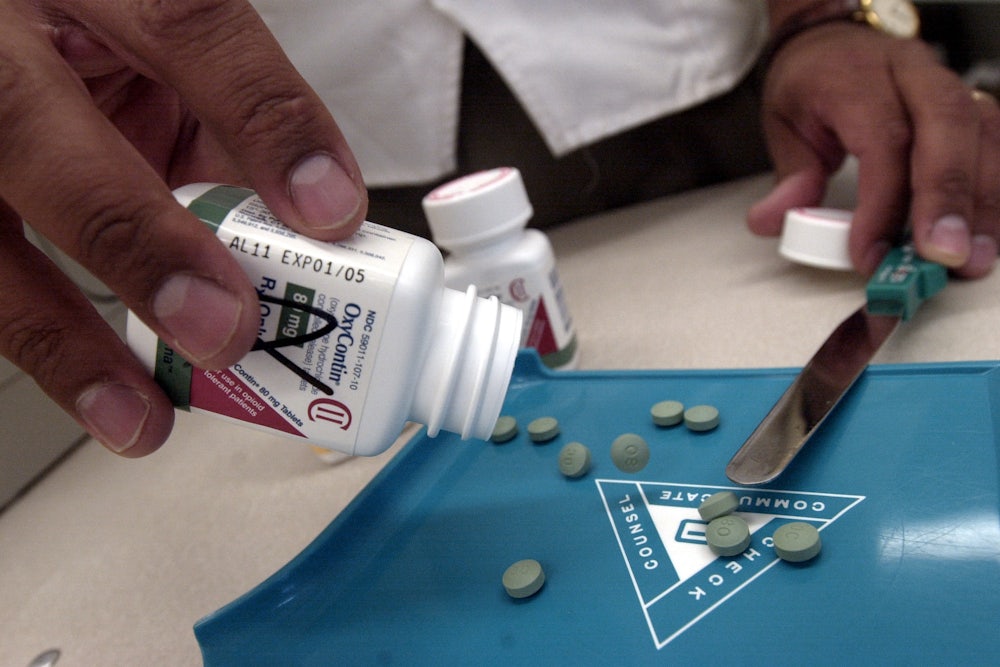

Under siege from thousands of lawsuits from federal, state, and local governments for its role in the deadly opioid addiction crisis, drug manufacturer Purdue Pharma reached a tentative settlement with some of the plaintiffs last week. In the deal, Purdue would transform itself through the bankruptcy process from a typical, profit-chasing drugmaker into a “public beneficiary company.”

It’s an offer that has been rejected by many of the attorneys general suing the company. They believe the proposed settlement doesn’t come close to compensating for the harm done by the flood of addictive OxyContin the company pumped into communities to pad its bottom line. Purdue, for its part, is moving ahead, filing Sunday night for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The two sides could square off in court as early as this week.

Nonetheless, the proposition raises an important question: If plaintiffs are open to the idea of turning Purdue into a public trust run by appointees of a federal bankruptcy judge—one that would distribute its profits to state and local governments—why not take one more step? Why not create the beginnings of a network of public pharmaceutical companies like those that already exists in such countries as Sweden, Brazil, and Thailand?

A United States public option for pharmaceutical production would address a range of problems in an industry rife with market failure. Some medications are out of reach for many patients who need them because of the high prices pharmaceutical companies charge. There are also dozens of drugs for which the for-profit drug industry is not meeting the demand because it’s not financially attractive.

The case for a public option is simple. First, publicly owned pharmaceuticals are free of the structural need to appease profit-hungry shareholders and are thus able to focus on public health priorities. They can work hand-in-hand with public health departments to assure that essential medicines—originally researched and developed with significant public spending—are in adequate supply and priced to be accessible to everyone who needs them.

The U.S. can learn from a number of countries with successful public pharmaceutical industries. China and India’s state-owned drug companies produce a large number of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and sell them worldwide. Sweden’s public company, APL, is one of the largest specialty pharmaceutical manufacturers in Europe. Brazil’s state-owned labs produce more than 100 essential medications that are offered to low-income patients at little or no charge. Among the innovations developed by Cuba’s state-run biopharmaceutical industry is the lung cancer vaccine CimaVax, which has been used to treat 5,000 patients across the globe, and is being tested in clinical trials in the U.S.

These examples expose the emptiness of industry arguments that public involvement in the drug industry will stifle innovation. In fact, it’s the increased profit-driven financialization of the industry in recent decades that is most responsible for strangling innovation. The largest U.S. drug manufacturers together have spent far more on marketing than they have on research. They also spend more on stock buybacks: A 2017 Institute for New Economic Thinking study demonstrated that many large drug companies “routinely distribute more than 100 percent of profits to shareholders, generating the extra cash by reducing reserves, selling off assets, taking debt, or laying off employees.”

Experience has shown that innovation is driven by the passion and knowledge of people free to focus solely on healing and hope, without having to worry about what Wall Street thinks. Insulin is a prime example of the difference a public pharmaceutical option could make. Managing diabetes has become a huge expense, consuming 20 percent of U.S. health care spending—and profit extraction by an oligopoly of insulin manufacturers is a key reason. Because prices have more than tripled in the past decade, diabetics put their lives at risk by taking partial doses or skipping doses altogether. There have been four publicly confirmed deaths thus far in 2019 attributed to diabetic ketoacidosis in patients rationing their insulin due to cost, according to the Right Care Alliance.

States like New York or California, and municipalities like New York City, would be ideal candidates for public pharmaceutical operations. Not only do they have market size, but they have robust research and health systems upon which to build. They also have political leaders and activists primed for leading the kind of democratic engagement that can make these operations accountable to the public and its needs.

Coupled with reforms such as a national pharmaceutical institute—which would ensure public investments in medical research can be harnessed for public benefit instead of co-opted exclusively for private profit—these public enterprises would produce both new medications and generics, and could offer them at or even below cost. For the average Type 1 diabetes patient, that would likely mean paying no more than about $70 a year for treatments that now cost upwards of $6,000 a year.

The 1998 tobacco settlement was the last big opportunity the nation had to build something lasting and transformative from the damage done by an industry—and that was squandered. Aside from some meager anti-smoking campaigns, a 25-year, $246 billion agreement did nothing to prevent the tobacco industry from creating a new addiction—vaping—with emerging, deadly consequences.