It’s one of the most famous thought experiments ever devised. “A cat is penned up in a steel chamber,” the physicist Erwin Schrödinger wrote in a 1935 paper, “along with the following device (which must be secured against direct interference by the cat): in a Geiger counter, there is a tiny bit of radioactive substance, so small, that perhaps in the course of the hour one of the atoms decays, but also, with equal probability, perhaps none; if it happens, the counter tube discharges and through a relay releases a hammer that shatters a small flask of hydrocyanic acid.”

The prevailing theory of atomic behavior among the early quantum physicists held that the atom in question, given the random chance that it might or might not decay, would have actually been both decayed and not decayed at the same time until the act of observing it placed it in one state or the other. But, as Schrödinger mused, this would also suggest that the cat in such a device would itself be both killed and not killed, dead and not dead—an impossibility suggesting that quantum models had missed something. “That prevents us,” he concluded, “from so naively accepting as valid a ‘blurred model’ for representing reality.” In other words, whatever ambiguities and complexities lay at the atomic and subatomic level, before the naked eye and common sense, only one thing could be true.

Last Thursday, the House Judiciary Committee voted to approve a resolution establishing new rules for its investigation into the Trump administration. “This investigation,” committee chairman Jerry Nadler said, “will allow us to determine whether to recommend articles of impeachment with respect to President Trump.” This was the latest iteration of a seeming escalation in the Judiciary Committee’s probe, which Nadler began to call a “formal impeachment” process early last month.

That semantic shift happened despite House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s public opposition to impeachment and the deep divisions within the Democratic caucus on the subject. While those divisions clearly remain, a majority of House Democrats now support impeachment. Democrats as a whole have, moreover, been vocally supportive of Nadler and the Judiciary Committee’s work.

But, crucially, they don’t seem to agree what that work actually is. The picture that emerges in pieces like Politico’s survey of sixteen House Democrats earlier last week, is of an impeachment that both is and is not happening, a process characterized entirely differently by different observers:

Sixteen House Democrats, in interviews, offered conflicting assessments of the status of the House Judiciary Committee’s investigation of Trump, which its chairman — Rep. Jerry Nadler — bills as an “impeachment investigation.”

“We have been in the midst of an impeachment investigation,” said Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), a member of the Judiciary Committee.

“No, we’re not in an impeachment investigation,” said Rep. Jim Himes (D-Conn.), a member of the House Intelligence Committee.

A third, Rep. Gregory Meeks (D-N.Y.), said the House is investigating to determine “whether or not there should be an impeachment investigation.”

The days since have not brought further clarity. On Wednesday, House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer told reporters that an impeachment investigation was not underway, before walking back his remarks later in the day. “I strongly support Chairman Nadler and the Judiciary Committee Democrats as they proceed with their investigation ‘to determine whether to recommend articles of impeachment to the full House,’ as the resolution states.” When asked whether he agreed with Nadler that the Judiciary Committee was now conducting an impeachment investigation at a Wednesday press conference, House Democratic Caucus chair Hakeem Jeffries urged the press not to get “caught up in semantical distinctions.” He went on to claim that he “hadn’t had an opportunity to review” the committee’s new resolution—which had been published by the press two days earlier.

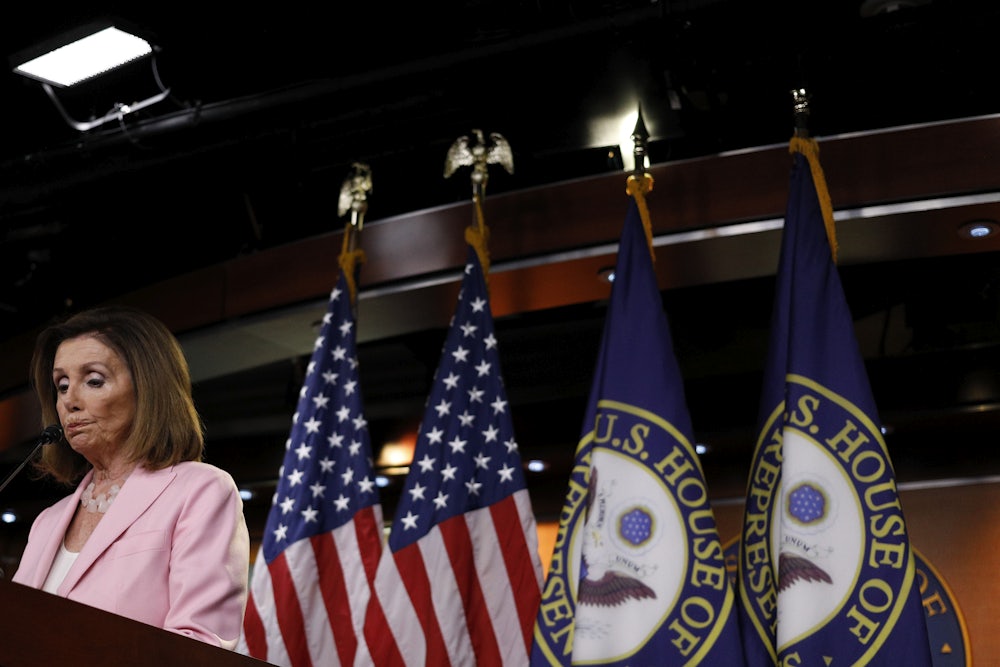

After the committee’s vote Thursday, Pelosi told reporters at yet another press conference that nothing had changed on the impeachment question and that reporters should focus the opposition of Senate Republicans to new gun control measures instead. “Why is it that you’re hung up on a word over here,” she asked, “when lives are at stake over there?”

Of course, congressional reporters might be less caught up on the word “impeachment” if Democratic leaders in the House would, for once, talk straight about what the Judiciary Committee is doing and what it means. Fortunately, one needn’t rely on House leadership to figure out what actually seems to be going on. We need only to pop open the chamber and have a look at the cat for ourselves.

Nadler’s statements of what he intends for the committee, the committee’s court filings, precedent from impeachments past, and the plain text of the Constitution make the situation clear. The House of Representatives has, through the House Judiciary Committee, initiated impeachment proceedings against the president of the United States. The Judiciary hearings set to begin this week and the committee’s ongoing investigative efforts will inform the committee’s decision whether or not to recommend articles of impeachment to the full House. If the Committee does recommend articles of impeachment, the full House will vote on them. If articles are approved, the president will be put on trial before the Senate, unless Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Senate Republicans move to block a trial.

Nadler’s trajectory has grown increasingly clear over the past few months. In July, both a Judiciary subpoena memo and a request in federal court for grand jury materials stated that the Judiciary Committee is working to determine whether it should “recommend articles of impeachment” against the president. As it has been widely reported, one of the benefits of this language is that it improves the committee’s legal standing to obtain evidence it’s seeking in its legal battles with the Trump administration. But the process Nadler has described is not just a legal strategy. The impeachment process, whether House Democrats know and acknowledge it or not, is happening right now.

It’s happening despite protests from Judiciary Committee Republicans, who routinely complain that the course Nadler has set out is illegitimate. “The Judiciary Committee became a giant Instagram filter,” Republican ranking member Doug Collins declared in his opening remarks for Thursday’s session. “The difference between formal impeachment proceedings and what we’re doing today is a world apart no matter what the chairman just said. What we’re looking at here is a filter to make you believe something!” He later asked whether he’d “missed a vote” of the full House officially authorizing an impeachment inquiry.

The Constitution offers no guidelines whatsoever as to how the House pursues an impeachment process, beyond noting that impeachment must begin in the House. Historically, every time the House has initiated the impeachment process, it has gone about it differently. Under Andrew Johnson, the House approved impeachment before articles had even been drafted. After they had been written, the House voted again to approve them and send them to the Senate. Under Richard Nixon, the House voted to authorize a Judiciary investigation and then drafted and approved articles of impeachment. Nixon resigned before things went further. Under Bill Clinton, the House passed a resolution authorizing the Judiciary Committee to conduct an impeachment investigation, but the committee did little to actively probe the revelations of the already released Starr Report. Later, a separate resolution with articles of impeachment was passed by the House.

Now, Nadler’s committee is conducting an investigation that may lead to the drafting of articles upon which the whole House will subsequently vote. Of these varied approaches to impeachment, there are none that can be said to be more constitutionally legitimate than the others. The Constitution does not even require a formal process of any kind to precede the drafting of articles. In fact, articles of impeachment against Trump have already been drafted and voted on multiple times since 2017. Had the House approved them, they would have been sent to the Senate for an impeachment trial—simple as that.

And yet an idea seems to persist that there is something like an official impeachment process which Democrats have yet to begin, and can only begin with the assent of the whole House. No such process exists. An impeachment happens when the House votes to approve articles of impeachment. The Judiciary committee is on the path to drafting those articles. The official impeachment process supporters are waiting for is the process that is taking place. Democrats are already impeaching Trump—and they’re already making a hash of it.

It’s an open question whether the mixed messaging from Democratic leadership about impeachment is the product of genuine confusion about procedure and what Nadler is trying to accomplish, or if it is an intentional effort by leadership to muddy the waters—allowing both impeachment supporters and impeachment opponents within the caucus to believe what they want to believe about what is taking place while Judiciary diligently continues with its investigation and public support for impeachment trickles upward.

If it’s the latter, Democratic leaders have outsmarted themselves. In the first place, a lack of clarity on what Judiciary is up to could undermine Nadler’s strategy of using the imprimatur of an impeachment investigation to win its battles for evidence in court. In an interview with Bloomberg this week, Michael Conway, the Judiciary Committee counsel during the Nixon impeachment inquiry, said that Steny Hoyer’s initial denial Wednesday that an impeachment investigation was underway would have been “legal malpractice.” The continued efforts of pressure groups like Need to Impeach to nudge Democrats toward impeachment suggests that the status quo is still unsatisfying to party activists. Dueling statements about whether impeachment is or is not already happening will also undermine vulnerable red state Democrats who are wary of impeachment, by making them seem confused at best—and duplicitous at worst—to constituents who want to understand what’s going on.

A mealymouthed muddle will not inspire confidence in the case for Trump’s impeachment among voters who could be convinced to support it. Instead, it could contribute to the impression that there is no there there—that if there were a strong case against Trump, Democrats would be much less wishy-washy and ambivalent about the whole thing.

No matter how Democrats, individually or collectively, choose to frame the impeachment process, Republicans will continue to freely claim that the Democrats want impeachment to happen. Republicans, in fact, are just about the only group the current messaging works for. During Thursday’s Judiciary Committee session, they took turns mocking Nadler’s resolution and Democratic divisions while the committee’s Democrats, as Bloomberg’s Billy House tweeted, “sat mostly and weirdly quiet.” “The strategy apparently,” he wrote, “is to not say anything that might inflame one side of their own party or another.”

This strategy, if it can be called a strategy, is a slowly unfolding disaster. It’s bad for impeachment supporters, bad for impeachment opponents, bad for liberals, bad for moderates, and bad for the country. It’s bad even for Nancy Pelosi, who will continue to face questions from journalists about how the Judiciary Committee’s investigation should be characterized no matter how much those inquiries annoy her and no matter how inconvenient she believes them to be.

It is also bad for the country. For only the fourth time in American history, the House has begun a presidential impeachment. Our representatives owe the American people clarity about this process and its significance. If confusion persists—if Democratic leadership continues to insist on this quantum superposition of political reality—a large share of the voting public will glean only this: The Democratic Party, perhaps more literally than ever before, does not know what it is doing.