In this Democratic primary, it can be difficult to distinguish between the candidates’ various criminal justice reform proposals—but at least they have them. Finally, maybe, Democratic presidential candidates no longer need to signal their “tough on crime” stance. They can propose that some criminal laws should be scrapped. They can commit to reducing the number of people in cages, whether that’s in a county jail or a federal prison. They can call for abolishing the death penalty (59 percent of Democrats polled by Pew in 2018 would want that, too). This is a sign of how far advocates for reform have come, not just in pushing elected representatives, but creating a political environment where candidates are almost trying to out-reform one another.

But the specter of “tough on crime”—some might remember 1988 Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis; more will recall his opponent invoking a man named Willie Horton—still lingers, and most of all for the people these proposals would leave behind. A candidate’s pledge to “end mass incarceration” can quickly crumble if it’s couched in carve-outs: legalize marijuana (but not opioids), automatically expunge criminal records after five years (but only for offenses that are not serious or violent), end sentences of “life in prison without parole” for youth (but only after they’ve served ten years, and only for crimes committed before their eighteenth birthday). All of that is what Kamala Harris proposed Monday in her plan, to, as the candidate explained in a post on Medium, “fundamentally transform our criminal justice system to shift away from mass incarceration and to invest in building safer and healthier communities.”

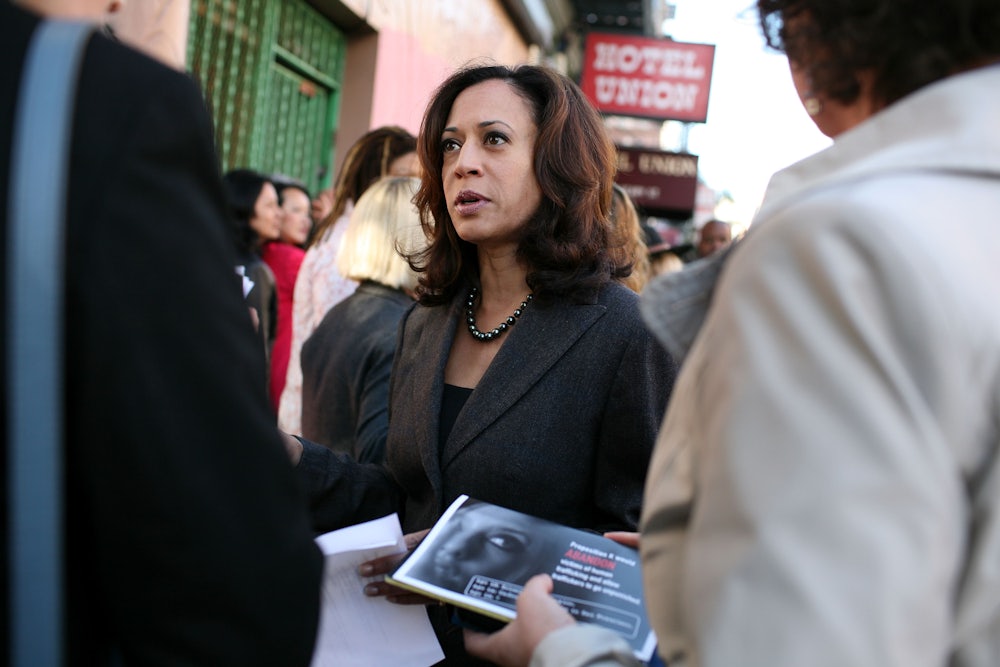

Harris leans in to her criminal justice resumé to convey her expertise in making such shifts in the system that once gave her such power. Before she arrived in Washington, D.C. in 2017, she had spent the previous twelve years as a prosecutor, as San Francisco’s district attorney, and as California’s attorney general. She held those roles before the nascent “progressive prosecutor” movement succeeded in replacing old, tough-on-crime types. Local prosecutors decide which people will be prosecuted and for which crimes, and Harris was once one of them—one who would likely not meet today’s current standards for a “progressive” prosecutor.

From the time Harris spent “working inside the system as a prosecutor,” her plan’s preamble reads, “Kamala has seen firsthand the fundamental flaws of the system.” She does not, however, ascribe any of them directly to her own conduct. Harris could, if she chose to, say clearly what actions she took as a prosecutor. She could draw on her experience to explain the kinds of cases that would fall outside her new plan. There can be no fundamental shift in this system without prosecutors examining past practices and understanding what it would take to change them. Harris, though no longer a prosecutor herself, could be a model for such accountability. So far, she has not been.

In an email exchange with the Harris campaign’s deputy national press secretary, Kirsten Allen, after the plan was released, I asked what the now-senator would have done differently as a prosecutor to better align with her vision today. Part of the reply pointed to a portion of a campaign video. “A lot of it comes down to accountability. And I say this as a former prosecutor,” Harris said in the clip. “When we talk about accountability in the criminal justice system, that word is always applied to the person who is arrested…. It is rarely applied to the system.”

As an example of accountability, Harris then described the open data system she launched as state attorney general. While any law enforcement agency that wants to make it easier for the public (including the press) to access such data deserves praise, there is a big difference between sharing data about potential misconduct and changing the system to prevent such behavior. Like claims to vague reforms, offering accountability through transparency comes down to what’s left out. The Harris open data project in California included demographic information on people that police across the state have killed, but it omitted the names of the officers.

Even more concretely, had Harris’s reforms been on the books when she was in charge of California’s penal system, some of those in prison now might never have been convicted or jailed. Then there’s those people who wouldn’t have been charged at all, like the more than 1,900 convictions for marijuana possession that she oversaw during her tenure as San Francisco district attorney. Harris today pledges to “de-emphasize criminal justice interventions in response to mental health issues.” But in 2008, she pursued an assault charge against a 56-year-old woman with mental illness who was shot by San Francisco police and severely injured. And not to be forgotten, there are those people who these proposed reforms would have left out, like women sentenced to prison for violent crimes committed in the course of defending themselves from violence—including those who may be deported upon release as a consequence.

To have a candidate like Harris bill herself as a reformer is a kind of step toward reform, but one easily lost in compromises. Rather than being a practice, “reformer” risks becoming a brand for Harris, one that provides cover for whatever proposals are later offered. Harris especially illustrates how the reform rebrand is incomplete: The prosecutor self she wants us to regard as an expert is still there in the archives, and still in the role she assumes on the presidential campaign stage.