July 1945, the engineer Vannevar Bush—one of the founders of the Raytheon electronics corporation, and director of the federal Office of Scientific Research and Development during World War II—published a meditative essay in The Atlantic. The scientific community had mobilized during the war to develop the atomic bomb. Now, he urged, it should turn itself with the same energy to the organization of human knowledge. He envisioned a device that may seem eerily familiar today: a desklike piece of furniture he dubbed the “memex,” which would make available and searchable all the accumulated written works of humanity, compressing entire encyclopedias and scientific libraries into a few square inches, and serving as an “enlarged intimate supplement” to individual memory. The memex, Bush suggested, could enliven people under the shadow of nuclear destruction: It would enable humanity to access the tremendous record of human experience, and direct it toward a shared common good.

How far the grim news from today’s technological frontier seems from Bush’s optimism. Amazon is rife with counterfeit and fakery. Facebook has been blamed for the dissemination of conspiracy theories and ethnic hatreds, and for allowing user data to be manipulated to influence elections. Uber can’t turn a profit even as its “gig economy” model undermines the notion of the steady job. YouTube’s algorithms sway restless young people to the most extreme racist right. Hand-held computers link us to the massive tech giants lurking in the background. There’s a whole genre of first-person essay about trying, and failing, to break addiction to the iPhone.

This was not how it was all supposed to turn out. For many years, Silicon Valley and the machines that came out of it were presented as personally, economically, and socially transformative, agents of revolution at both the level of the individual and the whole social order. They were democratizing, uncontrolled, anarchic, and new. Most of all, they were supposed to be fun—to open up a space of play and freedom. How is it, then, that just a few decades in, we find ourselves trapped in a dreary spectacle that seems to replicate the old patterns of exploitation and dominion in almost every sphere, but with a creepy new intimacy?

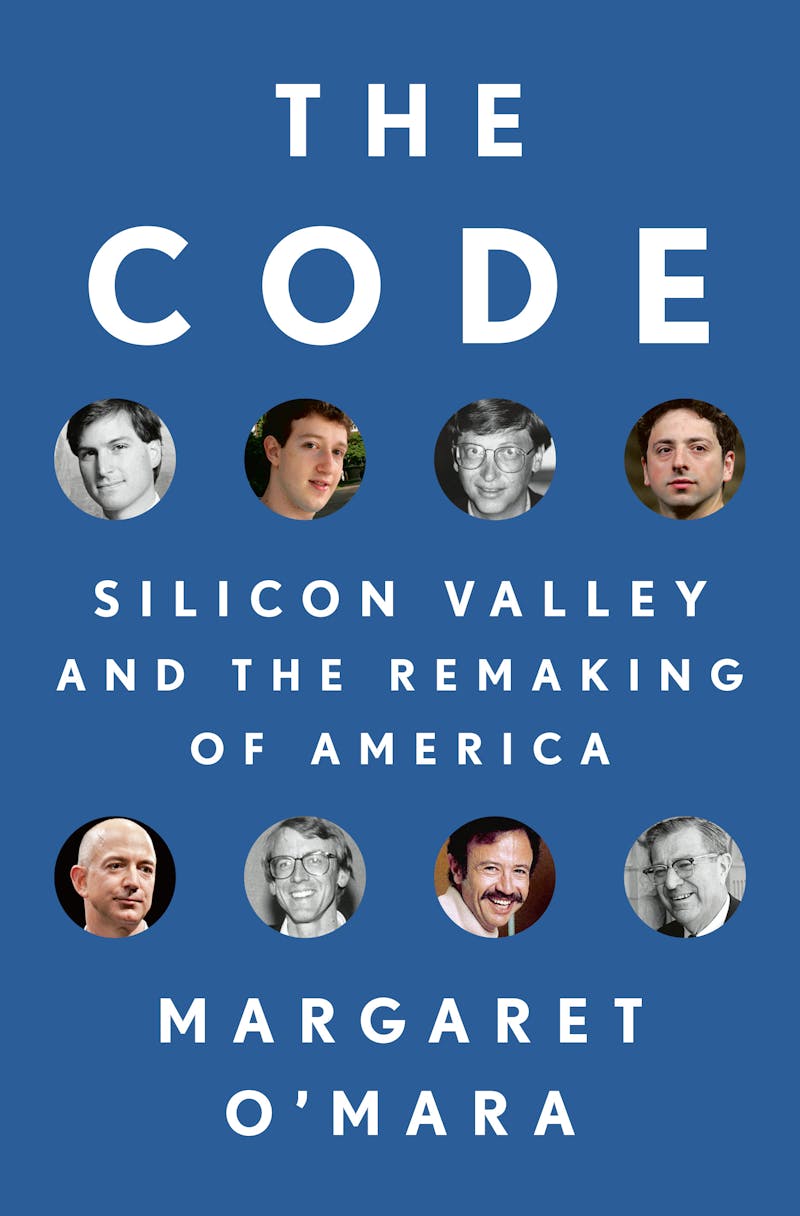

Margaret O’Mara’s book The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America traces just how our uneasy present deviated from what was promised at the outset. O’Mara embeds Silicon Valley in the sweep of American political history, offering a vision of the social landscape that produced the modern technology industry. She shows how Big Tech did not simply spring Athena-like from the brain of Steve Jobs, but rather took shape out of the dilemmas and possibilities of the Cold War, the particular culture of Northern California, and the economic debates of the 1970s and 1980s. What comes through most powerfully in her narrative are the wild social hopes once projected on to computers. These magical machines were supposed to provide a solution to the economic and political problems of the late twentieth century, a way to transcend and break free of the confining aspects of postwar capitalism. This was a feint, a way of imagining a miracle fix to tensions and conflicts that had no easy resolution. Computers, O’Mara suggests, have long been metaphors as much as machines.

At the end of World War II, nothing seemed particularly special about Silicon Valley. It was a predominantly agricultural community, known for growing cherries, apricots, and plums. In the 1950s, it developed into a distinctly unglamorous suburb dotted with bungalows, similar to dozens of others around the country. “Mid-1950s Santa Clara Valley was merely a smaller-scale Los Angeles, home to aerospace companies, light manufacturing, and some smart academic scientists,” O’Mara writes. Boston looked far more likely to emerge as the technological capital of the future: It had MIT, Harvard, and easier access to the pools of money and investors needed. Computer experimentation was happening all over the United States.

But even in the early postwar years, some aspects of Northern California gave it a distinct advantage. Most important was Stanford University. Stanford was an institute of higher learning that had never been committed to an abstract intellectualism but had long pursued connections to private industry. For example, it dispatched a faculty member to the first semiconductor company in the Valley, founded by the mercurial William Shockley, co-inventor of the silicon transistor and a Palo Alto native. When in the early 1950s Stanford opened a 350-acre industrial research park, the university was able to provide a space to entrepreneurial Stanford graduate students: people such as Bill Hewlett and David Packard, who moved their electronics company to the park in the early ’50s. Hewlett-Packard’s corporate culture served as a prototype for the later ideal of the Silicon Valley firm: putatively non-hierarchical and idealistic, giving out stock to employees to encourage their loyalty, and certainly not tolerating unions. Packard, the more politically interested of the pair, joined these management practices to a bruising critique of the “socialism” he thought pervaded the Kennedy and Johnson administrations: “They would take our wealth and distribute it as they see fit!”

Despite HP’s skepticism about government, public investment was crucial to the rise of Silicon Valley. Postwar California benefited from an excellent public school system as well as the stellar state universities. Even more important, companies based there could take advantage of the federal money flooding into the defense industry at the height of the Cold War. Often, origin stories of Silicon Valley have focused on its countercultural ethos: the way that the freewheeling norms of the 1960s helped to shape an anarchic work culture. While attentive to this history, O’Mara outlines the way the defense industry nurtured a parallel culture, one that—though far more politically conservative—also encouraged a certain kind of dedicated idealism about the work, a sense that it was about more than profit. The Cold War infused the study of science with the political mystique of countering tyranny through inventing new machines.

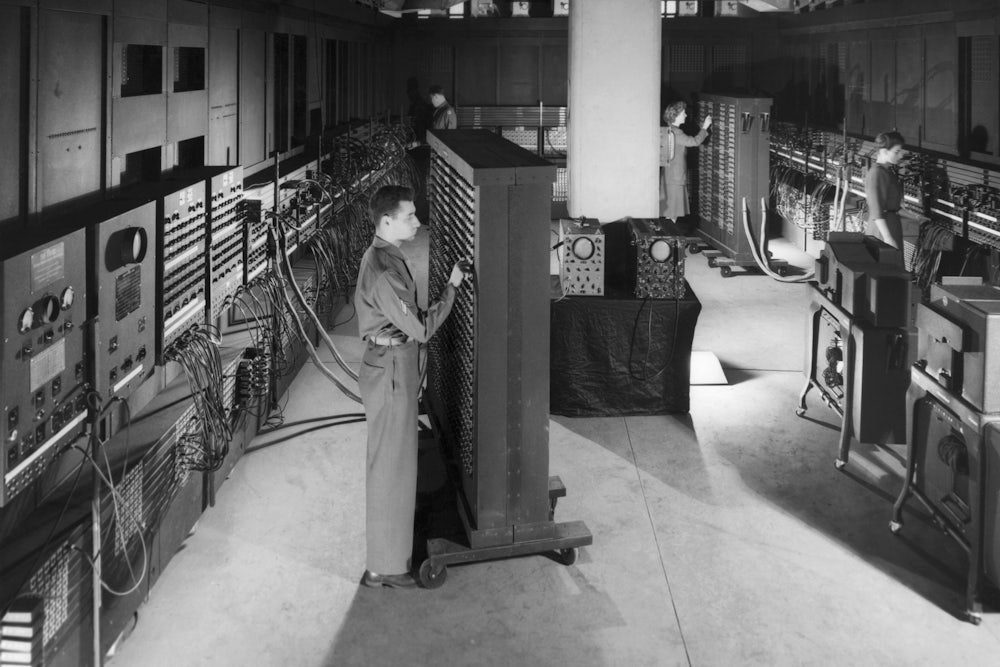

Northern California became a center of advanced electronics: transistors and semiconductors, rather than computers, at first. (The first known use of the name Silicon Valley comes from a 1971 article about “the semiconductor wars” in trade journal Electronic News.) Early computers were gigantic and expensive, and geared toward business goals. In the mid-’60s, those who wanted to use computing power had to rent space on mainframes in what were known as “time-sharing” arrangements. Slowly, though, the vision of a world in which everyone owned his or her own private computer began to emerge. At a demo in December 1968, engineer Doug Engelbart debuted a roster of now-familiar innovations: He typed commands on a keyboard that showed up on a computer screen 30 miles away, using a mouse and a blinking cursor to complete humdrum household tasks such as editing a grocery list. It was a harbinger not only of technical but of social development, an intimation of a world in which computers were ordinary machines made to be operated by people as they went about their daily lives, and who had no expertise whatsoever in actually programming them.

A buoyant, optimistic grassroots tech culture coursed through Palo Alto in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Its artisanal sensibility was radically different from the thoroughly corporate tech world of today. Then, being into computers often meant going IRL to a meeting with a few other enthusiasts, bringing along questions about the desktop you were putting together in the garage. O’Mara describes the “homebrew” clubs and “people’s computer centers,” where enthusiasts could learn programming languages and trade electronic parts. “Are you building your own computer? Terminal, TV typewriter? Device? Or some other digital black-magic box? Or are you buying time on a time-sharing service? If so you might like to come to a gathering of people with like-minded interests,” read one mimeographed invite to the first meeting of the Homebrew Computer Club in Menlo Park in 1975. “Ready or not, computers are coming to the people,” wrote Stewart Brand in Rolling Stone in 1972. “That’s good news, maybe the best since psychedelics.”

But the cheery hippie pragmatism of hacker culture always coexisted with an underlying anxiety about the ultimate purpose of the new machines. The French sociologist Jacques Ellul worried in 1954 about a future in which devices were capable of relentlessly subordinating human desire and using it to gain political and social control: “Our deepest instincts and our most secret passions will be analyzed, published and exploited,” he wrote. Journalist Vance Packard warned in 1964 of the rise of “banks of giant memory machines that conceivably could recall in a few seconds every pertinent action … from the lifetime of each citizen.” In the late ’60s, New Jersey Democratic Representative Neil Gallagher campaigned for new federal legislation to protect privacy: “Raw data are now extracted in much the same way teeth are pulled,” he proposed, “either under the ether of uninformed consent or ripped out by the roots.” Congress passed the Privacy Act in 1974, to regulate the way that the federal government could use or disseminate information it collected about citizens. This early effort to limit the power of the dossier, O’Mara notes, had nothing to say about what private corporations might do with any information they were able to glean.

Whatever fears might have surfaced in the ’60s and ’70s were tamped down as the 1980s approached, and as politicians of all stripes hoped Silicon Valley could show the way forward for the country as a whole. The economic slowdown and political upheaval of the ’70s marked a crisis of legitimacy for a social order based on affluence. Defeat in Vietnam rattled the military-industrial complex that once had funded the space race. No easy future was evident for the old manufacturing sector, as its owners closed the engineering marvels of an earlier moment and moved production overseas.

Rather than address the myriad crises that followed in the wake of deindustrialization, a generation of politicians (from both sides of the aisle) turned instead to the shiny ideal of entrepreneurship. In the ’80s, “supply-side” economics and calls to cut capital gains taxes represented attempts to transcend the gloomy fears of the ’70s that growth might be a thing of the past. Supply-siders promised that the problems were just ones of incentives and politics; once the thicket of regulations and taxes was cleared away, the American miracle would resume. And Silicon Valley—where venture capitalists held ownership stakes in the firms they spurred forward, so different from the staid stockholders who sat back to let corporate bureaucrats do the work—was a social laboratory, exhibit A of what happened if you simply didn’t regulate and let the market work its magic.

The thud of the assembly line would be replaced by the playfulness of computer labs (with the video-game–playing Palo Alto Research Center of Xerox Corporation and the gleeful pot-smoking over at Atari in its early days predating Google’s ball pits and snack stands by several decades). The conflictual realm of collective bargaining would disappear in favor of workplaces that had simply never been unionized. The particular type of intelligence cultivated and rewarded by tech—a synthesis of engineering ingenuity with canny appeals to consumers and an ability to intuit what they would want next—could replace the familiar factories and their boring products. Who needed another car?

Silicon Valley was the alternative. Its financing, its management practices, its geography, and most of all its ideology of invention and meritocracy made it appear—to its promoters—the opposite of the slow-moving bureaucratic corporations of the Northeast and Midwest. Computer technology had never been regulated the way telephones were; a set of antitrust cases in the 1960s helped to guarantee that networked computers would not be subject to the same degree of state power that governed telephone utilities in the mid-twentieth century.

Celebrating Silicon Valley became a way of bridging political differences. Ronald Reagan—once a General Electric employee, after all—touted the wonders of technology as just one more American marvel, speaking to students at Moscow State University in 1988 about the computer revolution. But the ideal of tech was bipartisan, as “Atari Democrats” such as Paul Tsongas of Massachusetts and Al Gore of Tennessee praised the promise of technology to change the world. No more need for politics, with all its mess and conflict. (Gore teamed up with Newt Gingrich to organize a “Congressional Clearinghouse on the Future,” which met monthly for brown-bag lunches on new-age topics like cloning and computers.)

The company that most successfully harnessed the ethos of the libertarian counterculture to a new vision of ’80s-style consumer capitalism was Apple. As O’Mara puts it, Apple “bridged the hacker world” of local computer labs with the venture-capital–fueled “Silicon Valley ecosystem”: “While baking countercultural credentials into its corporate positioning from the start, Apple was the first personal-computer company to join the silicon capitalists.” Steve Jobs had been a member of his Homestead High School Computing Club, and his partner Steve Wozniak came out of the Homebrew culture. They took this ethos into the firm they built, which from its earliest days embraced the ideal of the personal computer as a symbol of individuality. Perhaps Apple’s most famous representation of this idea was its 1984 Super Bowl ad, which featured armies of faceless black-and-white clones moving in lockstep, subordinated to the images playing on a giant screen. Suddenly a lone figure broke free to destroy the mainframe, and then the screen went dark except for a glowing rainbow apple: “On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.’”

Apple’s vision of liberation, though, always meant the freedom to become fantastically wealthy. When the company went public in December 1980, its valuation quickly climbed above that of those staples of the old economy, Ford and Bethlehem Steel. By the end of 1984, Apple executives celebrated their triumph over the mainframe with 19 holiday parties, one featuring a Dickensian village peopled by performers in period garb.

The last chapters of The Code trace the emergence of the internet. AOL and Netscape and the start-ups of the dot-com boom all make their appearances and are quickly replaced by Amazon, PayPal, Facebook, and Google. O’Mara notes the connections between the new Valley and the old: Facebook, for example, had its early offices in a part of the Stanford Research Park that had once been home to Hewlett-Packard. Government money continued to matter, too, despite all the talk of decentralization: Anarcho-libertarian Peter Thiel, one of the founders of PayPal, also became involved with starting a data-mining company named Palantir, whose primary client was the CIA, and even Google got its start when two Stanford grad students were working on the Digital Libraries Project, funded by the federal government.

Despite the rapid pace of technical development, it has been hard—even for the earliest of adopters—to sustain the old utopianism. Doubts about the meaning of this new world have proliferated throughout society, even in the Valley itself. In the epilogue to The Code, O’Mara suggests that Silicon Valley as we have known it is in decline. New programmers will go to different and less pricey locales (San Diego?). But the crisis extends beyond Silicon Valley as a place. The very confidence in technological entrepreneurship it once embodied may prove to have been a product of the late twentieth century more than an enduring feature of our political landscape.

O’Mara’s version of the Valley remains one dominated by the entrepreneurs who led its development. At times, this means that its social history is less present than it could be. We do hear mention of the “tens of thousands of employees (disproportionately female, Asian and Latina)” who labored at the semiconductor factories of the Valley—in numbers far greater than the professional white men who “were the faces the tech industry presented to the world.” The Code features profiles of women (both white and black) who worked in the industry in its early years, giving a sense that it was not as monolithically white and male as the endless parade of Steves and Marks and Daves and Peters might suggest. O’Mara briefly discusses the fraught relationship of the tech industry to East Palo Alto, where Black Power activists organized in the late 1960s, and also to San Jose, where it was discovered in the early ’80s that toxic chemicals were leaking from the semiconductor plants into the water supply. But these stories are not at the center of The Code. Ultimately, O’Mara seems less concerned with Silicon Valley as a place than with its inscription into a political narrative that posed the sunny inventiveness of California as the alternative to Rust Belt gloom.

The Code’s great strength is that it captures the various meanings projected onto Silicon Valley—the way that computers and their makers became the bearers of a certain economic symbolism, representing “the resounding triumph of the agile new market economy over the lumbering bureaucracies of old.” Even though O’Mara herself seems far from an opponent of or a skeptic about technology, her book brings to mind earlier accounts of the socially embedded nature of machines. In 1952, the British historian Eric Hobsbawm wrote an essay titled “The Machine Breakers” for the journal Past and Present, in which he sought to present Luddism and the wrecking of industrial machinery as a reasonable tactic at a certain point in the development of the British labor movement, rather than an irrational and futile gesture. Workers, he argued, were hardly possessed by a passionate and unthinking fury that led them to destroy the mechanical looms and ricks. Instead, they did so in particular and targeted ways in order to augment their bargaining power at specific moments.

One is hard-pressed to find machine-breakers today; the writers chronicling their agonized efforts to quit the iPhone and the tech moguls panicking about the effects of screen time on their kids’ brains are the closest we’ve come so far. Still, The Code brings to mind Hobsbawm’s arguments about the politics of technology. For it suggests that the widespread discomfort with the technological regime is not only about the machines themselves. We live in a moment when the political consensus of the ’80s and ’90s is being called into question. Faith in unregulated free markets has led to the dominion of the rich; the disinvestment in the public sector has led to the hollowing out of the institutions upon which democratic society rests. The tech industry seemed at one point to make material many dreams of the free market. It provided an image of a highly competitive economy that rewarded intelligence and daring, funded by venture capitalists with an ownership stake in the companies they built. As people challenge the social certitudes that rose in the ’80s, the slicker, brighter future that machines promised looks shakier too. This deepening unease about technology—and the spaces that have nurtured it, like Silicon Valley—is testament to the shifting politics of our time. Inchoate and uncertain though this discomfort may be, it is an expression of desire for a new order.