Jim Mattis has a story to tell. For the first two years of the Trump administration, he was one of a handful of high-ranking figures who more or less openly pitched themselves as necessary checks on an impulsive, childish, and ignorant president. Six months into Trump’s presidency, for instance, Axios reported that Mattis and then-Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly had made a pact that one of them had to be in the United States at all times, presumably for the purpose of stopping the president from doing something dangerous. Given the reports that trickle out every few hours these days—a recent story about Trump asking the National Security Council to look into using nuclear bombs to disperse hurricanes is only slightly crazier than the median leak—one must imagine that Mattis, who served as Secretary of Defense, had a better sense of the president’s fitness for office than just about anyone else in the country.

But that is not the story that Mattis is going to tell, even as he promotes his new memoir, Call Sign Chaos. In that book, he writes “I’m old fashioned. I don’t write about sitting presidents.” According to NPR, he mentions Trump by name only four times, all in the first two pages of the prologue. Instead, he opts for mealy-mouthed cliché, writing soaring but vague prose about the need to protect democracy from tribalism and other threats. A recent excerpt in The Wall Street Journal could be considered a subtweet if you squint a bit. Mostly, it reveals the failure, during the early Trump administration, of the so-called adults in the room, a group that never had the tools or the courage to restrain a corrupt and erratic president.

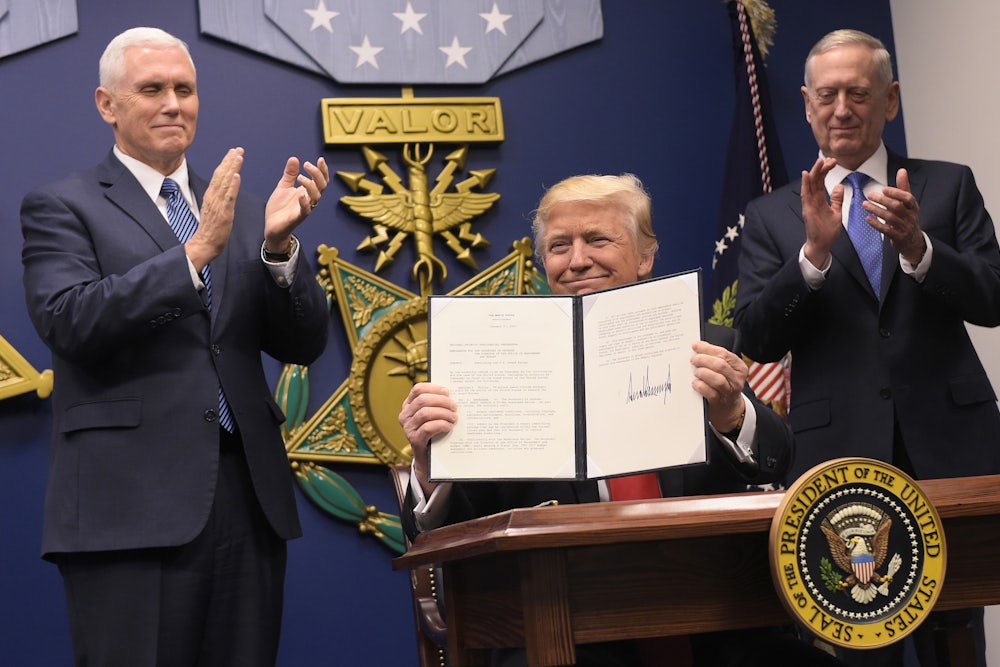

When he picked Mattis as his defense secretary nominee in December of 2016, Trump thought he was getting General Patton, or perhaps more likely, a character from one of the ultraviolent action movies the president is fond of. Trump reveled in Mattis’s nickname “Mad Dog,” repeatedly citing it at rallies and, at one point, claiming to have coined it. For Trump, the moniker was a sign that he had hired a killer, someone who would do whatever it took to get things done. Instead of “Mad Dog,” however, Trump got something different: a temperate, thoughtful commander who saw it as his duty to preserve the country’s relationships with its allies while the president pissed them away. By the end of Mattis’s time in the Pentagon, Trump was calling him “Moderate Dog”—proof, if any more were needed, that the president’s supposed mastery of nicknames is greatly exaggerated.

In the Journal excerpt, you do get a glimpse behind the curtain, a sense of what Mattis was advocating during his time as head of the Department of Defense. There are pleas for cooperation with allies and a return to the alliances that Trump has repeatedly slammed for being too costly. “Wise leadership requires collaboration; otherwise, it will lead to failure,” Mattis writes. “Nations with allies thrive, and those without them wither. Alone, America cannot protect our people and our economy.”

The closest Mattis comes to naming Trump is when he alludes to the danger of “polemicists”—a word that is a tad too lofty for the daily torrent of abuse emanating from the president’s Twitter feed. “A polemicist’s role is not sufficient for a leader. A leader must display strategic acumen that incorporates respect for those nations that have stood with us when trouble loomed.” In these sections you get a vague sense of Mattis’s beef with Trump: He’s impulsive. He doesn’t value alliances. His foreign policy is reckless and creates long-term risks. Above all, you get the sense that Trump didn’t much listen to Mattis and his ilk—something that was obvious to anyone paying even the slightest attention to the White House. Despite that, Mattis’s sense of duty apparently compels him to avoid naming the president, or go into even the slightest detail about what he witnessed in the White House.

But there’s also a strong sense of Mattis’s extreme disconnect from political reality. “Unlike in the past, where we were unified and drew in allies, currently our own commons seems to be breaking apart,” Mattis writes. “What concerns me most as a military man is not our external adversaries; it is our internal divisiveness. We are dividing into hostile tribes cheering against each other, fueled by emotion and a mutual disdain that jeopardizes our future, instead of rediscovering our common ground and finding solutions.”

What Mattis seems to be railing against is the idea of anyone criticizing the foreign policy consensus that has governed Washington for the entirety of his military career. If not that, it’s not clear what he even means. There was certainly no period in American history in which the country was wholly unified on foreign policy or anything else. Mattis, whose military service began during the Vietnam War, should know that as well as anyone. Any critique of tribalism from Mattis, meanwhile, has a significant asterisk, given that he went along with both Trump’s so-called Muslim ban and spearheaded the administration’s prohibition of transgender soldiers.

This shallow critique also points toward the wider failure of the “adults.” They hoped that vague platitudes about consensus and democracy would be enough to constrain a renegade president. When Mattis quit last December, a number of pundits fulfilled their word counts and airtime quotas worrying what would happen now that the last grownup had finally left the White House. The eight months since haven’t been great, to be sure, and Trump’s behavior has subjectively gotten a little bit worse, but there’s no sense that the president is more dramatically unleashed—that without Mattis, Kelly, and former Chief Economic Adviser Gary Cohn, there is no one left to stop Trump. As bad as things are now, they aren’t markedly worse than they were when the grown-ups were around. It turns out that everyone, Mattis included, was at recess.