Billionaire fossil fuel mogul David Koch died Friday. Though he will rightfully be remembered for his role in the destruction of the earth, David Koch’s influence went far beyond climate denial. Ronald Reagan may have uttered the famous words “Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem” back in 1981—but it was David Koch, along with his elder brother Charles and a cabal of other ultrarich individuals, who truly reframed the popular view of government. Once a democratic tool used to shape the country’s future, government became seen as something intrusive and inefficient—indeed, something to be feared.

“While Charles was the mastermind of the social reengineering of the America he envisioned,” said Lisa Graves, co-director of the corporate watchdog group Documented, “David was an enthusiastic lieutenant.”

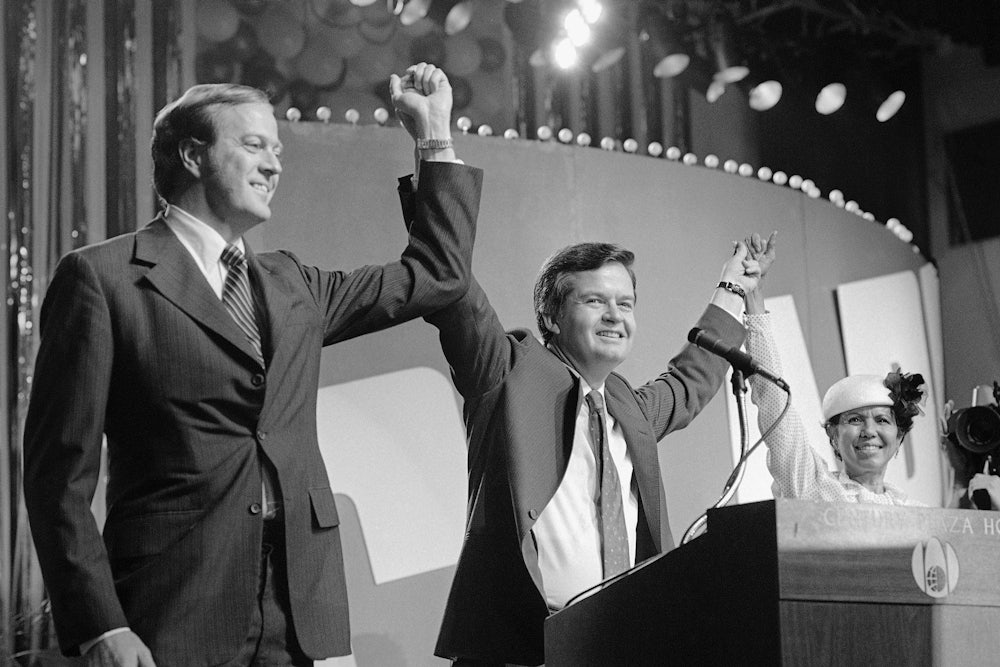

David Koch was particularly instrumental in legitimizing anti-government ideology—one the GOP now holds as gospel. In 1980, the younger Koch ran as the vice-presidential nominee for the nascent Libertarian Party. And a newly unearthed document shows Koch personally donated more than $2 million to the party—an astounding amount for the time—to promote the Ed Clark–David Koch ticket.

“Few people realize that the anti-American government antecedent to the Tea Party was fomented in the late ’70s with money from Charles and David Koch,” Graves continued. “The Libertarian Party, fueled in part with David’s wealth, pushed hard on the idea that government was the problem and the free market was the solution to everything.”

In fact, according to Graves, “The Koch-funded Libertarian Party helped spur on Ronald Reagan’s anti-government, free-market-solves-all agenda as president.”

Even by contemporary standards, the 1980 Libertarian Party platform was extreme. It called for the abolition of a wide swath of federal agencies, including the Food and Drug Administration, the Department of Energy, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the Federal Aviation Administration, the Bureau of Land Management, the Federal Election Commission, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, the Federal Trade Commission, and “all government agencies concerned with transportation.” It railed against campaign finance and consumer protection laws, the Occupational Safety and Health Act, any regulations of the firearm industry (including tear gas), and government intervention in labor negotiations. And the platform demanded the repeal of all taxation, and sought amnesty for those convicted of tax “resistance.”

Koch and his libertarian allies moreover advocated for the repeal of Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and other social programs. They wanted to abolish federally mandated speed limits. They opposed occupational licensure, antitrust laws, labor laws protecting women and children, and “all controls on wages, prices, rents, profits, production, and interest rates.” And in true libertarian fashion, the platform urged the privatization of all schools (with an end to compulsory education laws), the railroad system, public roads and the national highway system, inland waterways, water distribution systems, public lands, and dam sites.

The Libertarian Party never made much of a splash in the election—though it did garner almost 12 percent of the vote in Alaska—but doing so was never the point. Rather, the Kochs were engaged in a long-term effort to normalize the aforementioned ideas and mainstream them into American politics. Building off the Libertarian campaign, Graves explained, “David and Charles then used their front groups to pull the Reagan Administration further to the right with their push to privatize across the board.” With their army of think tanks, front groups, lobbyists, and media ties, this multimillion dollar effort to shift the Overton Window grew for nearly four decades, culminating in the takeover of many core political institutions, federally and in key states. The duo additionally capitalized on the anti-government Tea Party movement, which they greatly helped along by bankrolling the conservative advocacy group Americans for Prosperity.

The Koch’s Ayn Rand–inspired hellscape has yet to completely come to fruition, but the ideas the duo promoted are now part of the regular discourse—and have been for a while.

In this respect, one of the most significant gaffes of the 2012 GOP presidential primary was as telling as it was embarrassing. During an early Republican debate, Texas Governor Rick Perry proclaimed that there were three agencies he would abolish if elected: He named the Departments of Education and Commerce, but, after much stuttering and stammering, admitted that he’d forgotten the third. Mitt Romney jumped in to suggest the Environmental Protection Agency; Ron Paul told the debate audience that there were actually five government agencies that should be axed. It sounded like a competition among Libertarians like Koch from 1980. “From time to time, you may forget about an agency that you are gonna zero out,” Perry later told a reporter. Though many political prognosticators found this whole exchange amusing, and Perry was soon out of the race (and on his way to running the Department of Energy, the agency that had slipped his mind that debate night), the Kochs were likely pleased by how much the party had absorbed their anti-government beliefs.

David and Charles Koch also achieved major legislative victories. In virtually all areas—from campaign finance and the environment to labor and transportation—their efforts have rolled back government oversight, perhaps not quite as much as they originally wanted, but still more than was thought possible in the late ’70s.

Neither David Koch nor his brother singlehandedly changed American politics. There were many factors that pushed America toward libertarian radicalization. But David was a central player and no whitewashing of history will change that.

“By his actions, David Koch’s creed was greed,” Graves explained. “He used the power of his wealth to try to transform that greed into a virtue, putting his name on museums, hospitals, and arts buildings while trying to hide from the public the millions he was spending to dramatically alter America.”

The younger Koch’s death will not change much about contemporary politics. The Koch conservative machine has already been set in motion to thrive well beyond David and Charles’ lifetimes. Those on the left, if they truly want to right the havoc that Koch wrought, must firmly reject the idea that government is somehow inefficient, wasteful, or tyrannical, and instead unequivocally reclaim it as the best means of solving shared problems. Recognizing that the ideological battle is far broader than any specific policy domain is critical to breaking the Koch legacy.

Rhetoric, though, only goes so far without the resource mobilization that made the Kochs infamous. The left should bestow upon David Koch the sincerest form of flattery: imitation. Developing a long-term, coordinated funder base—one that fervently fights for governmental programs—is paramount. This is a strategy that must supersede any individual’s vainglorious pursuit of the presidency.

The hatred David Koch inspires postmortem cannot be blind to what can be learned from his legacy. Change is difficult, but with persistence, it is always within reach. The question is only whether the left will have the same determination to reverse Koch’s legacy as he did in creating it.