America now divides into two classes: those who have lived with social media–laden smartphones since childhood, and the rest of us. Note how we elders are now the exception, rather than the rule, since our time will never come again. A profound and irreversible change in the grain of ordinary life has taken place, and the kids who have swiped iPads from infancy are now old enough to be forming significant political communities online (see: Politigram, the community of anarcho-capitalist teens). Their socially-augmented reality has arrived, but our understanding of their ways has not kept pace.

Liza Mandelup’s new documentary Jawline finds a window into the way teenagers use the internet now, offering an unusually intimate view of the new economy of social media stardom—a rare privilege in these times, when we are divided into little online enclaves by our own algorithmic prisons. There’s trouble afoot in teenage social media paradise, Mandelup has come to warn us, and there are no adults in attendance—and if they are, they’re not exactly supervising.

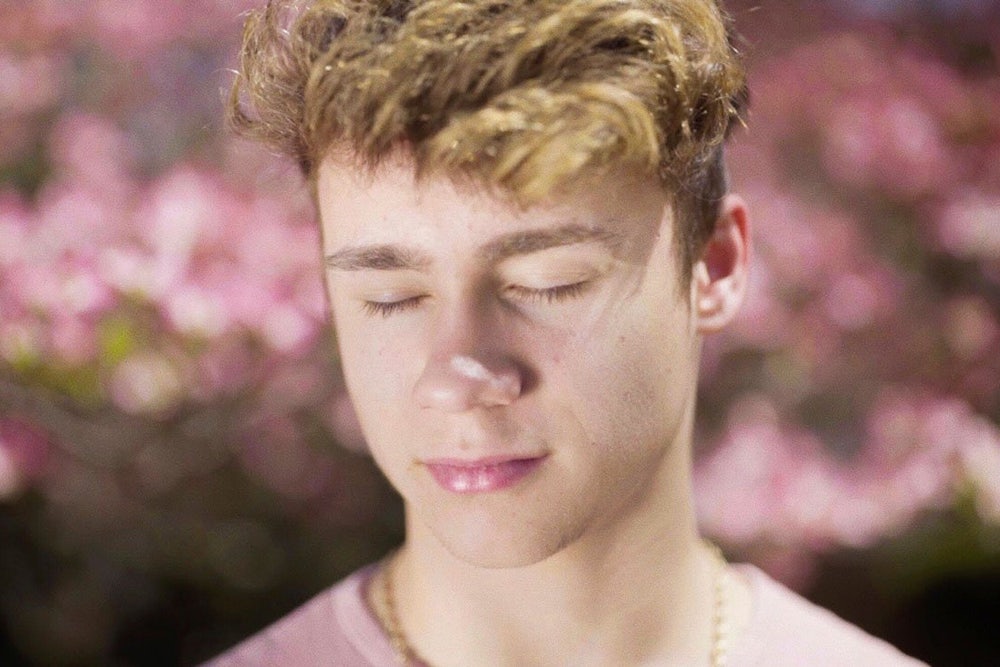

We meet Austyn and an unnamed friend in the first scene of Jawline, as they try to take flattering portraits against a brick wall in their hometown of Kingsport, Tennessee. They’re ordinary kids. Instagram shoot done, they bound down the hill, teenage-boy limbs jangling. Back in his bedroom, where he shares a bed with his even ganglier brother, Austyn records a video of himself singing along to an R&B song, which he then uploads to a social media platform edited to double-speed so that he looks like a robot singing a chipmunk ballad to whatever tween girl has logged on. Austyn’s innate goodness beams out of him as he signs off, “Don’t let anyone’s opinions keep you from chasing your dreams!”

For a teenage boy, Austyn is extremely sweet, though he has good reason not to be: His mother speaks openly about being miserable and broke, and his father was abusive before he left. But Austyn has reacted to the hardship in his young life by becoming a kind of motivational speaker, an online coach you can also have a crush on. “Fame to me is really important,” Austyn says. “When you become famous, you have a lot of people look up to you. And so when I can get famous, I can be positive and influence them to become positive and then influence others.” After they’re done filming they find no food in the house, so Austyn and his brother go down to swim in the creek behind their house, splashing in the green water like innocent young satyrs.

Mandelup oscillates between the online and real worlds, never letting you forget that these are real children with real lives. It all falls into place when we follow Austyn to a fan meet-up at a local mall. Girls flock around him, against a hissing, hypnotic soundtrack. Why do they love him so much? He’s “mature and sweet,” the girls say, not like the boys at their school, who say horrible things. He says they’re all beautiful. One girl presses money into his hand and all but forces Austyn to buy a horse-shaped scooter, so that he can ride it around the mall and she can follow him and take pictures.

Mandelup demonstrates that the desire of teenage girls to be understood is, in fact, the fire in this industry’s engine. Mandelup films them at fan conventions, where remarkably smart and self-aware young women describe how much they need the support their social media icons provide. Some have addict parents or live alone. “I feel like their joy is our joy,” one girl sobs, as nearby girls tangle up in hyperventilating embraces, their hair falling across each other’s shoulders. Austyn is to them what Leonardo DiCaprio was to preteens in the early aughts: a desexualized pretty boy to project upon from the safety of one’s own home.

Unlike DiCaprio, however, these girls can touch their idols, even demand the selfies and hugs and kisses that their convention ticket money entitles them to. And, much like the child movie-stars of yesteryear, these idols are not seeing all the profits. Mandelup introduces us to an 18-year-old social media manager named Michael, who brags about his power and contacts with the top brass at Instagram. He’s mean, though evidently smarter than his charges. “For the fifth time,” Michael yells in one scene at a shirtless boy who is trying to call a social platform on a Saturday, “musical.ly is closed!”

Michael finds kids who are getting great engagement on Instagram (or on Twitter, or YouNow, or various other permutations of the same thing) and then signs them up, which means bullying them into a tight schedule of branded content production and sending them “on tour,” meeting fans. Then he skims the profits. Michael sees no reason why adults should be the ones to try to capitalize on the “social media gold rush,” as he calls it, and anyway they don’t understand how it works.

This is the kind of big break Austyn is praying for, and it happens when a Texas agency sends him on a tour. It seems fun enough. But as soon as the tour is done, Austyn starts to lose followers, and his fervently-held dream is in danger. Before he knows it, he’s dropped out of high school and his “manager” won’t pay him for any of his work.

Morale shaken, Austyn ends up back in Kingsport, broker than ever, only now shorn of the sweet naïveté that made him appealing in the first place. Jawline turns out to have been a bait-and-switch, as the fantasy of Austyn’s fame dissolves into regular old Tennessee poverty. In an interview provided with the movie’s press notes, Mandelup notes that, “In this world that I’m documenting, everyone’s exploited.” For Austyn has ended up more isolated than ever, his one consolation—social media—ruined forever. The girls have moved on.

A word on Mandelup’s method. Her work is both adjacent to and radically different from the reality TV documentary style that so dominates entertainment now. On her site, you can see that she has made branded content for Dove and websites spun off from print magazines like Dazed Digital and i-D. Mandelup began her career as a scout for Levi’s, where she learned that she had a knack for casting.

This background helped Mandelup to identify Austyn as the perfect rising social star to profile from among the hundreds of teens she interviewed—she managed to catch him right before his dream took flight, then went Hindenburg. But it also speaks to the quality of her filmmaking, which mixes sharply observed narrative with dreamy, pastel colors and a shoegaze soundtrack. This hazy style is recognizable from the commercial visual world of recent years: the viral social videos and hip ad campaigns whose “aesthetic” grew out of Tumblr culture, not traditional advertising.

Both being of social media and looking at social media, Mandelup brings a sense of native sympathy to Jawline, while also importing the best of the internet’s visual achievements into her work. Jawline is something new, marking the moment that documentary becomes truly commensurate with teenage reality right now. It’s Michael’s world: We’re just living in it.