Humans and animals who stumble across a brightly colored blue-green or red pool don’t always recognize the threat. Toxic algal blooms aren’t high on many people’s radar. Vacation-goers obliviously wade into ocean and lake waters that can cause gastrointestinal or respiratory problems. They eat contaminated fish and shellfish with potentially lethal consequences. Dog owners unknowingly allow their beloved pets to frolic in toxic ponds—leading to death within hours.

Toxic algae is one of the quickest-spreading deadly effects of the climate crisis in the United States. As the Arctic’s glaciers melt and the Amazon’s rainforest burns, America’s lakes, rivers, and coastlines are being increasingly infiltrated by several different types of brightly colored, toxic algae bacterium that thrive in warm, nutrient-rich conditions. A report released by the Environmental Working Group earlier this month found toxic algae appearing in more bodies of water, at higher quantities, and earlier in the summer than ever before. It also found that “climate change is making things worse, as scientists predict that warming waters coupled with fertilizer and manure washing off farm fields during heavier and more frequent rains may accelerate the frequency and intensity of harmful algal blooms in freshwater.”

While toxic algae blooms are supposed to be a regular occurrence in the summer, researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently forecasted that 2019 could bring some of the most abundant blooms in recent years. Toxic algae is no longer a minor inconvenience, disrupting diners’ seafood menus for a few months. It’s a neon threat on shores across the country, devastating individuals and communities, animals and people alike, as humanity belatedly struggles to respond. In states like New Jersey and Florida where algal blooms have already devastated both fishing and tourism economies, elaborate political fights—some rife with conspiracy theory—have broken out over how to manage the crises. And although 68 percent of Americans get their drinking water from lakes and rivers, algae toxins are not regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

These photos provide a glimpse of toxic algae’s frightening spread across the United States in recent years.

Green patches in this July 30, 2019 Landsat 8 satellite photo show where Lake Erie’s algal bloom was most dense, making water unsafe for recreational activities. Around the time of this image, the bloom covered about 300 square miles of Lake Erie’s surface; by August 13, the algae had spread across 620 square miles.

Toxic cyanobacteria surround a feather in Owasco Lake, which supplies the city of Auburn, New York, with drinking water. Only some forms of cyanobacteria—also known as blue-green algae—contain toxins. But where they do occur, cyanotoxins are “among the most powerful natural poisons known,” according to the CDC, and are especially dangerous for dogs.

This brown tide in Banana River at Cocoa Beach, Florida, in February 2018, was caused by an Aureoumbra lagunensis algae bloom. When Aureoumbra lagunensis dies it depletes water oxygen levels, killing fish. This was the fourth brown tide to hit the region in recent years. In a prior bloom in 2016, volunteers filled 80 dumpsters with more than 50 tons of dead fish.

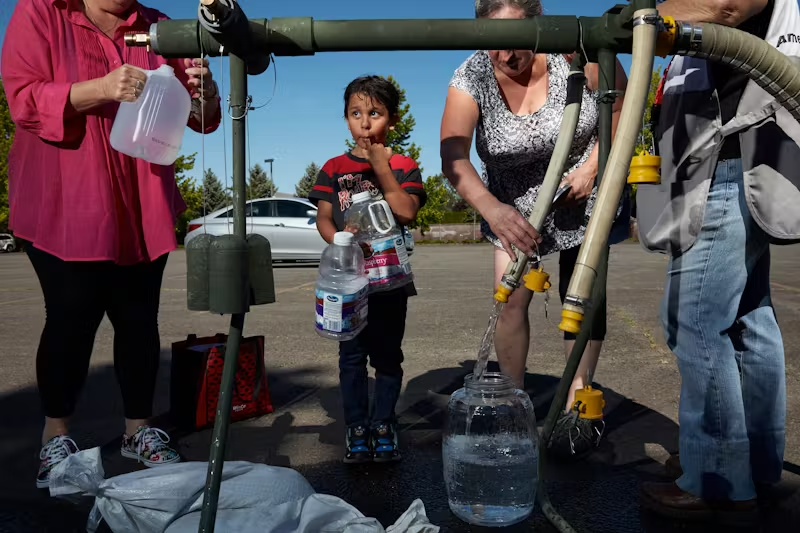

Santiago Plato, age five, and his grandmother, Monique Resch, fill water bottles at a drinking water distribution point operated by the Army National Guard in Salem, Oregon. In May 2018, Salem health officials issued a “do not drink” notice for children under six years old due to a toxic algal bloom in Detroit Lake that infiltrated the city’s water supply.

A cormorant—a large aquatic bird—suffers from brevetoxin poisoning at the Clinic for the Rehabilitation of Wildlife in Sanibel, Florida, in 2018. Brevetoxin is produced by blooms of Karenia brevis, commonly known as red tide. Mass die-offs of fishing birds commonly occur during red tide blooms, because the birds eat fish and crustaceans contaminated with the toxins.

Kelly Sloan, Katie Goulder, and Jack Brzoza of the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation carry a dead loggerhead sea turtle from the beach in July 2018. That summer, a record number of threatened loggerhead sea turtles and critically endangered Kemp’s ridley sea turtles died during a red tide bloom on the west coast of Florida.

Heather Stout and her son Teegan give their eleven-year-old dachshund Nike medicine for his cough, which his veterinarian said has been exacerbated by the red tide in Don Pedro Island, Florida, in July 2018. The family has avoided the water all summer, Heather said, and usually wears masks outdoors for airborne toxins.

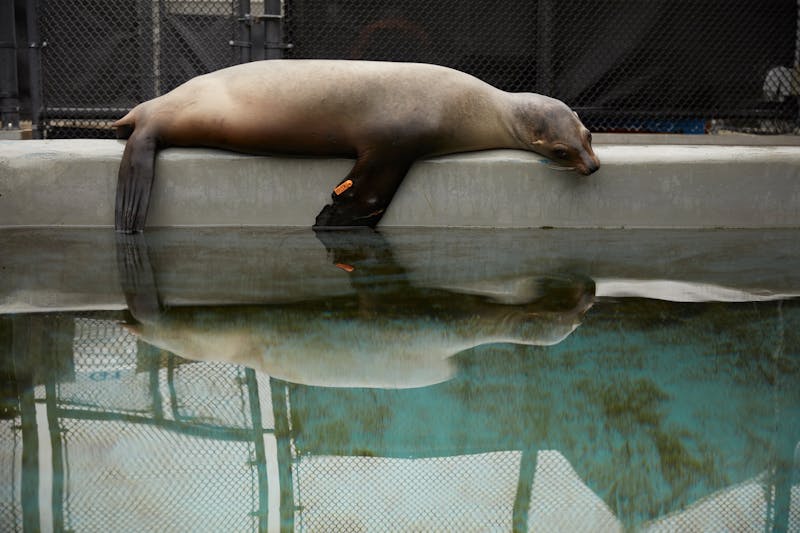

A California sea lion is treated for domoic acid poisoning at The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, California, in July 2018. Domoic acid is produced by a type of algae called Pseudo-nitzschia australis. It can cause brain damage and death in marine mammals, and amnesic shellfish poisoning in humans.

The upper Harraseeket River in Maine is one of the few remaining mud flats productive for clamming, now that shellfish harvests are often restricted for months at a time due to toxic algal blooms. The restrictions have had “a devastating impact on our business,” said Chad Coffin, a local clammer. “People don’t want to eat shellfish because they read in the newspaper you could get brain damage.”

Thousands of dead fish wash ashore during a red tide algae bloom in Sanibel, Florida, in July 2018.

Donna Sellers packs her car in Cape Coral, Florida, before driving to North Carolina to escape health problems she believes are due to red tide exposure. Sellers, who works full-time in a beachfront hotel, said she’s been experiencing lethargy, aching muscles, numbness in her extremities, blurred vision, nausea, and low-grade fever since the algae arrived in 2018.

Debby Grovak protests Florida Governor Rick Scott’s inaction on toxic algal blooms in Sarasota, Florida, in July 2018. Hours earlier, Grovak joined a group of about two hundred people to raise awareness about the harmful impact of red tide algae blooms, which at the time were afflicting coastal communities from Florida’s Panhandle to its southern tip.

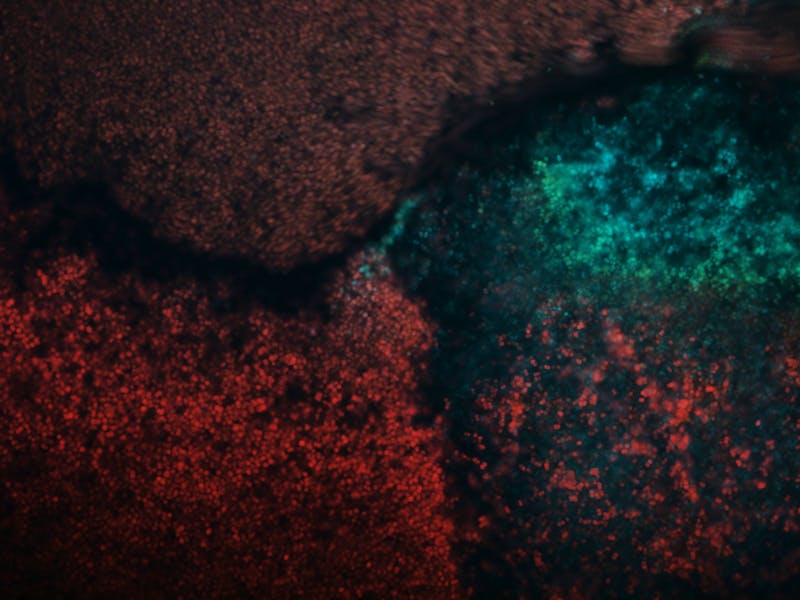

Microcystis aeruginosa—magnified here at the UTEX Culture Collection of Algae in Austin, Texas—is the most common freshwater cyanobacterium, whose blooms are commonly called “blue-green algae.”

A toxic blue-green algae bloom covers the Lake in Central Park, New York City, in June 2018. The algae, which poses a threat to young children and pets, has been discovered in three New York City parks in the last month.