Better known to most Americans for its picturesque beaches than its vast petrochemical reserves, Trinidad and Tobago boasts the most robust economy in the Caribbean. It has also, in the past year, become one of the premier destinations for Venezuelans trying to escape an escalating crisis.

In its ongoing attempt to push Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro out of office, the Trump administration has appointed Elliott Abrams—a divisive former Reagan- and Bush-era official associated in Latin America with regime-change plots and atrocity coverups—as special envoy; has slapped Venezuela with additional sanctions; and has recognized opposition politician Juan Guaidó. According to one estimate, U.S. sanctions since 2017 have caused the deaths of at least 40,000 by restricting access to funds needed for food, medicine, and other essential imports.

Maduro remains in power. And Washington’s aggressive posture has exacerbated the refugee problem in the Caribbean, putting nations traditionally close to the U.S. in a difficult position that has brought issues of American paternalism to the fore and encouraged some to seek greater partnership with China—viewed as a less demanding and interventionist ally.

For decades, as economic forces have ebbed and flowed, people have emigrated freely between Venezuela and Trinidad and Tobago, separated by only seven nautical miles. As Venezuela’s economic crisis worsens, the island of 1.3 million has been overwhelmed by a surge of people attempting to avoid the fallout.

In June, a crowd of protestors gathered at a sports stadium in downtown Port of Spain. “Rowley must go. Close our borders. Rowley must go,” they chanted.

The chant echoed a rising tide of frustration among many Trinbagonian citizens, vexed by Prime Minister Keith Rowley’s weak response to what Refugees International has called the worst humanitarian crisis in the Americas in modern history. The United Nations estimates there are currently 4 million Venezuelans living abroad due to the crisis at home. Since 2017, some 40,000 to 60,000 have arrived in Trinidad and Tobago according to UN figures—the highest influx in the Southern Caribbean.

West of Trinidad, Aruba and Curaçao have also been inundated with large flows of people. As of January, the islands had received 16,000 and 26,000 refugees and migrants, respectively. Ill-equipped with porous borders and limited spatial capacity (Trinidad and Tobago is slightly larger than Rhode Island), small islands have struggled to formulate an adequate response. Even large South American nations like Peru, which along with Trinidad recently implemented visa restrictions on Venezuelan nationals, are beginning to buckle under the weight of the migrant flow.

The migrants themselves, meanwhile, are growing increasingly desperate. In the days prior to the protest at Queen’s Park Oval, thousands of undocumented Venezuelans had lined the unshaded block south of the stadium attempting to secure Rowley’s “amnesty”—a policy created by the administration promising freedom from deportation and a one-year work permit for all Venezuelan nationals that registered between May 31 and June 14, no matter their legal status. Those who were brave enough to answer the government’s call scrambled to reach one of only three centers—two in Trinidad and one in Tobago. Some spent their last dollars and waited for days in the hopes of submitting paperwork. As the temperature climbed above 90 degrees it was reported that some pregnant women and young children had collapsed.

Addressing the nation in May, Prime Minister Rowley vowed that “international agencies” would not convert the island into a refugee camp: “Trinidad and Tobago is a tiny dot in the mouth of the Orinoco River.... We are humanitarian, we are caring, we help. But the help that Trinidad and Tobago can give has to be limited. This little island cannot be the solution to millions or hundreds of thousands of migrants leaving Venezuela.”

In May, accounts emerged in local media that authorities had closed the southern port of Cedros, one of the main arrival points for passenger boats from Venezuela, and where many people arrive legally to buy food and supplies that have become scant and overpriced amid the turmoil. There have been reports that Trinidad and Tobago’s Coast Guard has prohibited vessels from crossing the country’s maritime border, sending passengers back to Venezuela, and detentions of migrants seem to be on the rise. In a video uploaded to Facebook on June 3, a group of Venezuelan men held at the Immigration Detention Center announced that they were on a hunger strike because they lacked access to proper medical care and had not yet been told by officials when they would be released. While conducting research at the country’s maximum security prison, University of West Indies (UWI) St. Augustine Law Dean Rose-Marie Belle Antoine told me she discovered the government was using the facility to house an overflow of immigration detainees.

Xenophobia seems to be rising. The Venezuelan “issue” has consumed the news cycle. Some Trinidadians fear that the new arrivals will threaten their job security and pull down already stagnant wages. In 2015, Trinidad experienced a recession due to falling oil and gas prices, and the current unemployment rate sits at 4.8 percent. On Facebook, comments from concerned citizens range from cautious optimism to blunt racism. “If you organise and coordinate the process properly there would be no problems. The system you put in place is inadequate,” one Facebook user wrote. “Back them up and send them back home we have more than enough of them already,” wrote another.

Althea La Foucade, head economist at UWI St. Augustine, believes the government should adopt a measured approach. Recent arrivals could be instrumental in revitalizing industries like manufacturing that have struggled to retain workers, but too many foreign nationals competing for jobs against local employees could raise the unemployment rate and adversely impact the economy. UWI economist Roger Hosein believes the islands could stand to absorb at maximum 54,000 low-end workers. “If we could increase employment in the agricultural sector,” he told me, “by having a biased work permit program that sends Venezuelan workers into the areas that generate foreign exchange or prevent the use of foreign exchange, by import substitute production, then these workers can add tremendous value to Trinidad and Tobago’s economy.”

Constructive ideas for how Trinidad and Tobago should respond to the influx, as well as increasing pressure from the U.S. to isolate the Venezuelan regime, are complicated by the countries’ relationship. The neighbors share oil and gas reserves and cooperate on hydrocarbon exploration. “The current prime minister wants to maintain that relationship [with Maduro] and it comes at a time when the U.S. administration is doing whatever it can to isolate Venezuela from its Caricom allies,” University of Alberta political scientist Andy Knight told me.

Last August, the two countries inked a deal that would allow Trinidad to purchase and export natural gas from Venezuela’s state-owned Dragon field at a rate of 150 million cubic feet of gas per day. But as turmoil in Venezuela delays the process, opposition parliament members have questioned whether the government’s continued liaisons with Maduro are wise given that the U.S remains Trinidad’s largest trading partner. Rowley’s opponents fear the island could be left hat-in-hand after green-lighting a billion-dollar infrastructure investment to pipe the gas, should the deal fall through.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration continues its attempts to sow division within Caricom—a regional body that promotes cooperation and economic development among Caribbean communities. Caricom members have overwhelmingly advocated for “non-intervention and non-interference in the internal affairs of Venezuela,” while calling on “all actors, internal and external, to avoid actions which would escalate an already explosive situation.” The U.S., hoping to isolate Venezuela as much as possible, has promised Caricom members financial investment to back opposition leader Guaidó. “The Caricom countries have become sort of a chessboard in this hybrid war the U.S. is trying to carry out,” University of California Riverside Research Associate Jeb Sprague told me.

Only four of 15 member states: the Bahamas, Haiti, Jamaica, and St. Lucia, have either denounced Maduro or recognized Guaidó as interim president. The majority, including Trinidad and Tobago, has backed the Montevideo Mechanism—a diplomatic initiative endorsed by Mexico, Uruguay, and the EU.

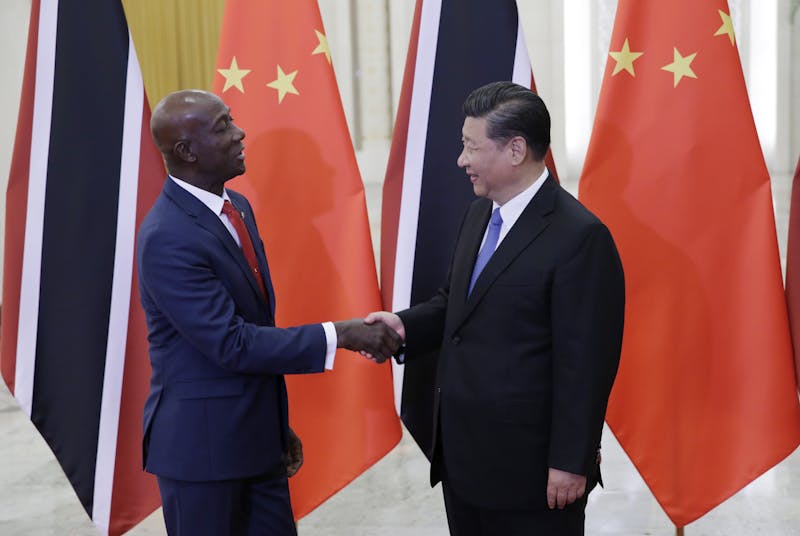

It’s a mark of independence from the U.S. that Knight says marks a waning of U.S. power in the region. Most Caribbean nations are dependent on tourism and rely heavily on imports, trading extensively with the United States. But, said Knight, “the Chinese government is actually beginning to raise its profile in the Caribbean and Latin American region, not unlike what it’s doing in other parts of the world with its Belt and Road initiative.”

Despite some well-deserved criticism, small Caribbean islands like Trinidad and Tobago have attempted to do their part to aid those seeking refuge, and have mobilized their countries’ resources to do so. Central Bank Governor Alvin Hilaire announced in May that it would cost the island an estimated $92 million ($620 million TTD) per year to host Venezuelan refugees and migrants—a large sum for a tiny country. Leaving smaller allies to shoulder the burden of American imperialism has both humanitarian and strategic risks. Island nations may turn against the refugees they are currently taking in. And Chinese partnerships may look more appealing as small states struggle with the fallout of U.S. actions.