Over the past four decades, the American political landscape has been littered with the wreckage of booster rockets from eagerly anticipated presidential campaigns that failed to successfully take off.

Begin with John Glenn, whom I profiled on the cover of Newsweek in 1983 just after the release of the film version of Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff. “Can a Movie Help Make a President?” the piece’s cover line asked—and, as is the general rule with most questions posed in a headline, the correct answer was “No.” Nebraska Senator and Vietnam veteran Bob Kerrey was considered a major 1992 challenger to Bill Clinton—until he ran. Basketball star Bill Bradley never got a clear shot against Al Gore in 2000. And then there was a celebrated also-ran named Joe Biden in 2008.

On the Republican side, the names alone provoke giggles. Rudy Giuliani had a hefty lead for the Republican nomination in all the Gallup polls in 2007. And maybe you remember Jeb Bush and his spendthrift ability to blow through $160 million in both campaign and Super PAC money without winning a single state—together with the woeful campaign-trail appeal that the candidate all but mumbled from beneath all that sunken cash: “Please clap.” Or take Jeb’s erstwhile Florida protégé, who was supposed to be the charismatic standard-bearer of a fearless new brand of Tea Party-inspired leadership: Marco Rubio, who is now best known for quoting Bible verses on Twitter between half-hearted defenses of President Trump’s agenda.

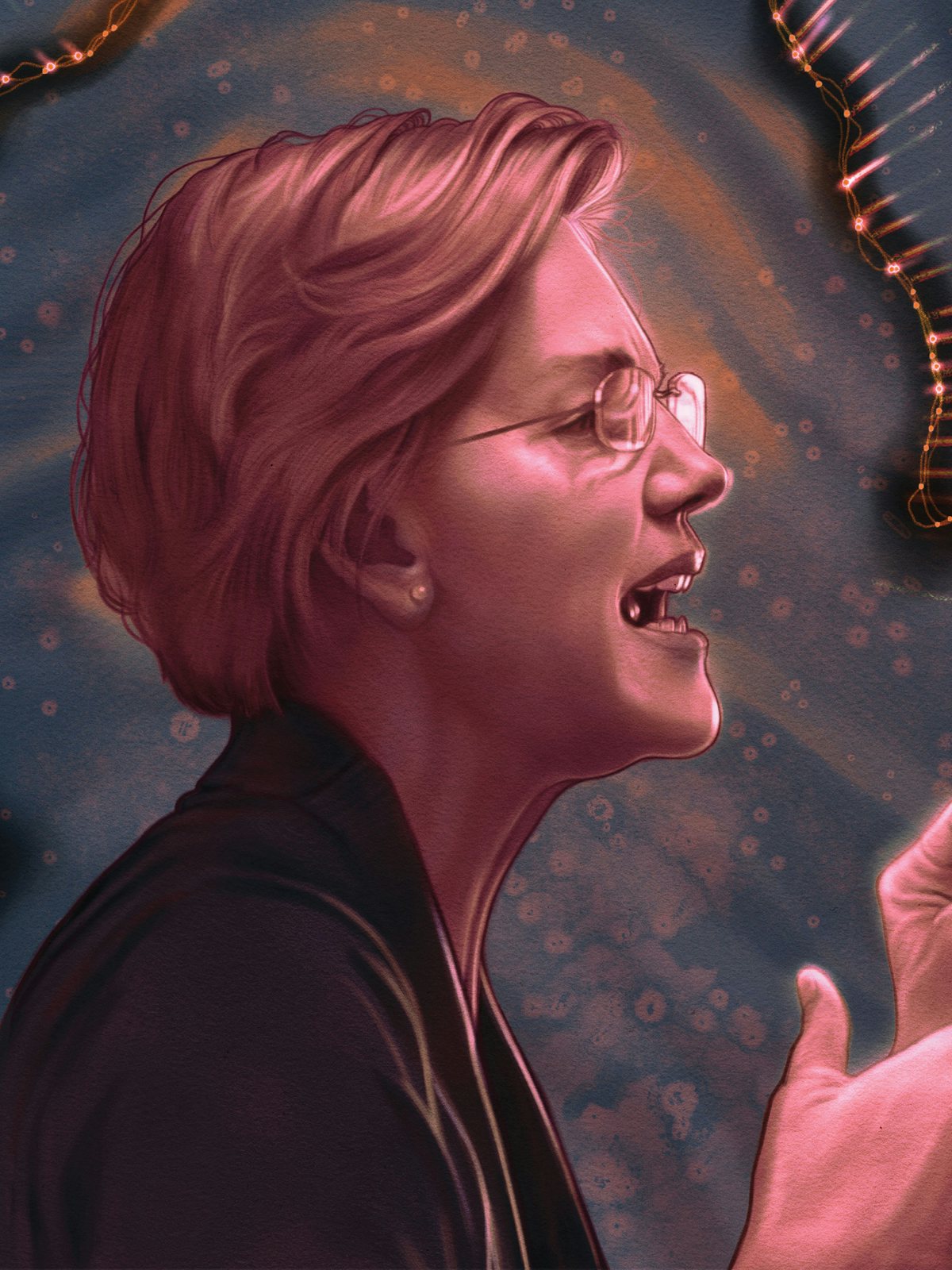

During the winter and early spring, it looked as if Massachusetts Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren would be the next entry in this parade of presidential pratfalls. But now that Warren again has as plausible a path as any candidate to the nomination, it’s worth remembering the way that the political railbirds and TV talking heads seized on her missteps (real and perceived) in the early going.

A cringeworthy New Year’s Eve livestream on Instagram featured the former Harvard law professor in her kitchen announcing out of nowhere, “Hold on a sec, I’m gonna get me a beer.” (The folksy outburst was as heavy-handed as the patrician George H.W. Bush stressing his love of pork rinds during the 1988 campaign.)

Since her first 2012 campaign to become a U.S. senator from Massachusetts, Warren has been grappling—none too successfully—with her prior claims of Native American ancestry. In an effort to still Donald Trump’s mockery of her as “Pocahontas” from his endless string of rally podiums, Warren in October 2018 released the results of a DNA test that showed her with a smidge of Native American ancestry dating back, at minimum, six generations. On her first trip to Iowa as a candidate in early January, Warren was pointedly asked by a voter in Sioux City (an apt locale), “Why did you undergo the DNA testing and give Donald Trump more fodder to be a bully?” By February, Warren was apologizing to the Cherokee Nation for implying that she was a member of the tribe based solely on the exceedingly thin DNA evidence.

Then there were Warren’s early strategic miscues. With her fierce opposition to Wall Street, she was never going to be fawned over at fund-raisers in Park Avenue living rooms and at Greenwich estates. Making a virtue of necessity in late February, she pledged to supporters in an email that she would be holding “no fancy receptions or big money fund-raisers only with people who can write the big checks.” This high-minded decision prompted in fairly short order the resignation of her finance director. Beltway insiders also derided the ban on big donors as a critical setback for Warren in the “money primary”—the crucial first scrum for candidates in an epically crowded Democratic field to realize maximum financial advantage. Politico called it “voluntary disarmament—a major risk that could send precious dollars to competing campaigns.”

It certainly looked that way, at first. By the end of March, Warren had raised about as much in the entire first quarter of 2019 ($6 million, not counting transfers from her 2018 Senate reelection) as Beto O’Rourke had collected during his first day in the race. And with a heavy initial investment in staff in states like Iowa and New Hampshire, Warren was burning money almost as fast it came in. These kinds of spending sprees normally occur much later in a primary cycle, as candidates begin springing for a heavy rotation of TV ads.

Her disappointing first-quarter fund-raising numbers solidified the orthodox judgment among campaign mavens that Warren’s moment had passed—that, if she ever had an opportunity, it was probably back in 2016. In April, the emerging conventional wisdom was that Warren faced a still formidable Bernie Sanders on her left flank, and she seemed a bit shopworn compared to flashy new figures like Kamala Harris and Pete Buttigieg.

If this were a typical political comeback story (the kinds that are immortalized in best-selling campaign books that later become HBO docudramas), Warren would rescue her campaign at this critical juncture with a dramatic gesture or bold decision. You could imagine the overheated prose: “Elizabeth Warren was angry. Her White House dreams were as bankrupt as her campaign treasury. In just a few hours, she....”

The ensuing campaign narratives could take any number of forms. Here’s a brief hypothetical sample: Maybe Warren would use the first debate to puncture the pretensions of a pesky rival, as Walter Mondale did in 1984 when he belittled Gary Hart’s “new ideas” with a line stolen from a hamburger-chain commercial: “Where’s the beef?” Or Warren might emulate a floundering Bill Clinton in 1992 by placing an unorthodox figure like James Carville in charge of every aspect of the campaign. She could even go the full John McCain route—jettisoning, as he did in 2007, the entire structure of his consultant-heavy operation to run a bare-bones, seat-of-the-pants campaign for the nomination.

But now for the dramatic revelation: Absolutely nothing changed with the Warren campaign. Like a sailboat caught in a summer squall, the good ship Liz’s Luck righted itself as soon as the winds died down. During the second quarter, Warren raised an impressive $19.1 million, narrowly topped only by Pete Buttigieg ($24.8 million) and Joe Biden ($21.5 million).

As Kristen Orthman, Warren’s communications director, put it, “We’re slow and steady—never too high, never too low. There’s going to be ups and downs. I think anyone who has ever worked in a presidential campaign will tell you that.” Yes, this sounds suspiciously like the baseball locker-room clichés mocked in Bull Durham. All that was missing was Orthman saying, “I’m just happy to be here. Hope I can help the ball club.”

But there’s also a good deal of truth in Orthman’s anodyne comments. David Axelrod, the chief strategist for Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012, who is neutral in the current presidential race, told me, “Since the Pocahontas thing, they’ve run a very smart campaign.”

Warren’s chief strategist, Joe Rospars, who was digital director for Obama in 2008 and 2012, also stressed the consistency of the campaign in a phone interview. “Everything in this campaign is of a piece of what she did that first day,” he said. “She walked out of her house and took questions from the media. And then she went to the office to make phone calls to people who had been fired up to volunteer in the early states. That’s a shorthand for what we’ve been doing this entire time—and what I expected us to be doing from here and beyond.”

All presidential campaigns are based on artifice. Candidates are never as heroic as portrayed by their staffs or as unswerving as suggested by their slogans. Bill Clinton didn’t always put people first—sometimes they took a back seat to his own psychological needs. And there were undoubtedly mornings when Barack Obama awoke a little short of hope and more wedded to the status quo than to change.

But by the flexible standards of politics, Warren is about as authentic as you are likely to get. Since she was elected to the Senate in 2012, she hasn’t delivered any dramatic swerves away from past positions, as did Bernie Sanders on guns, Kamala Harris on criminal justice, or Joe Biden on ... well, it’s a lengthy list.

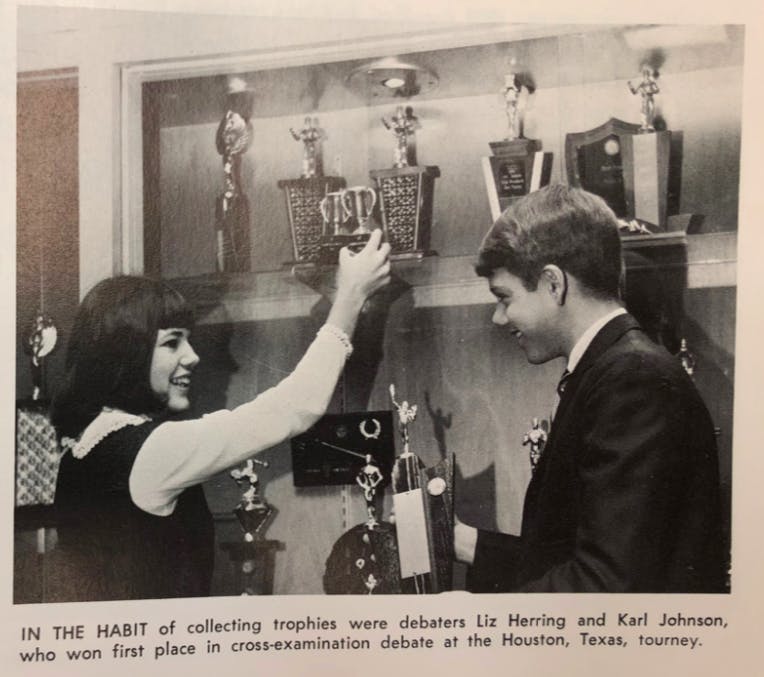

Instead, the transformation that shaped War-ren’s life came in the mid-1990s. A fledgling and largely apolitical Harvard law professor, Warren was brought in as an adviser to a federal bankruptcy commission set up by Bill Clinton. The person who played the largest role in Warren’s turn toward public life was former Democratic Representative Mike Synar, the commission chairman. Synar had unsuccessfully debated the formidable Warren in high school in Oklahoma, and he drew on that firsthand knowledge of her sharp polemic style to plunge her into the Washington fray—albeit in a regulatory panel devoted to what was then a middling policy debate. Nevertheless, Warren set about doing her work in the same stolid, implacable fashion that her aides now say defines her campaigning style. Along the way, her work with the commission—together with a subsequent battle with Biden, a senator loyal to the credit-card companies headquartered in Delaware, over the Bush White House’s regressive 2005 bankruptcy bill—set Warren on her steady leftward journey.

Warren has been a national celebrity since 2009, when she appeared with Jon Stewart on The Daily Show to explain the financial crisis. (In her 2014 autobiography, A Fighting Chance, Warren describes being backstage and suffering from “gut-wrenching, stomach-turning, bile-filled stage fright.”) But as Warren advisers are fond of pointing out, she is still a novice at electoral politics, especially compared to all her plausible rivals for the nomination. Yes, the other senators, the governors, the mayors, and former mayors in the 2020 Democratic field all sought elective office before she entered partisan politics in 2012. Even the then–28-year-old Pete Buttigieg ran for Indiana state treasurer in 2010.

Warren was able to leapfrog the traditional résumé demands of statewide candidates via inadvertent boosts from both a timorous Barack Obama and the most inept Democratic Senate candidate in recent memory. In 2011, President Obama decided that Warren’s zealous advocacy on issues such as bankruptcy and consumer debt was simply too toxic to survive a GOP filibuster in the Senate, so he declined to designate her the first director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which she had championed and set up.* Warren’s consolation prize proved to be an enormous political opportunity: a 2012 nomination, without a primary, to become a U.S. senator from Massachusetts.

Normally, ambitious Bay State politicians like Warren’s colleague Ed Markey (first elected to the House in 1976) have to wait decades for a Senate seat to open up. But in 2010, Democrat Martha Coakley managed to fritter away the Senate seat held by the late Ted Kennedy for nearly a half-century by losing a special election to Republican Scott Brown. (Coakley’s stunning defeat, among other things, badly complicated Obama’s efforts to pass the Affordable Care Act in the Senate, by depriving the chamber of a filibuster-proof majority.) Coakley’s botched Senate run meant that in 2012, for the first time since 1978, a GOP-held Senate seat would be on the ballot in Massachusetts.

Warren’s race against Brown was the most expensive in the country that year—one that also demonstrated Warren’s prowess as a fund-raiser by raking in $42.5 million. According to those who worked on that 2012 race, Warren boasted four distinct skills that separated her from most first-time candidates: an ability to make decisions; good political instincts; a willingness to learn; and an insatiable appetite for campaigning. As Warren said at the time, “I will go as long as you want me to. I’ve just got to have my water. I’ve got to have my tea. And my food. I’ll eat anything. It doesn’t have to be special. It can be from McDonald’s.”

Although her margin of support was significantly behind Obama’s in Massachusetts, Warren did what generations of Massachusetts Democratic candidates before Martha Coakley had done: She handily won the Senate seat, with 54 percent of the vote.

If elected in 2020, Warren would enter the Oval Office at the age of 71 and would be the oldest newly inaugurated president in history. Despite the political culture’s frequent cruelty to older women (see Clinton, Hillary), Warren’s age is almost never mentioned by anyone—friend or foe—in the campaign. My hunch, in fact, is that if you asked Democratic voters whether Warren was closer in age to Biden (currently 76) or Kamala Harris (54), 87 percent would say “Harris,” and the other 13 percent would have “no opinion.”

Watching Warren bound out of a house for a backyard event in Waterloo, Iowa, in June, I could easily understand why she seems fresh and others (particularly Biden and 77-year-old Bernie Sanders) seem tired. In early campaign events, Warren projects a sort of coiled energy—propelling her constantly in motion, pacing and talking as she clutches a hand mic. Dusk was settling over this town meeting in a racially mixed, working-class neighborhood, but what riveted the crowd of about 250 Democrats was the way that Warren told her life story.

Autobiography, of course, is the coin of the realm for presidential candidates, with the conspicuous exception of Sanders, who portrays himself as emerging fully grown in Vermont, raging against a “rigged system.” But Warren approaches the campaign life narrative in a tellingly sideways fashion, one that doesn’t hit all the traditional heroic, bootstraps-plying themes of many Democratic campaigners. (Yes, the broad arc of the saga is still heroic, but with many unanticipated reversals along the way.)

She not only talks about her hardscrabble childhood in Oklahoma (“I still remember when we lost the family station wagon.... It was when I learned words like ‘mortgage’ and ‘foreclosure.’”) but also speaks with apparent honesty about her own life’s misadventures. “I have a story that has a lot of twists and turns in it,” she said in Waterloo. “It’s not a straight-line story. Here’s how my story begins: I got a scholarship to college. Yay! And then at 19 I fell in love. Yay!”

By the time Warren got to the second “Yay,” her audience was laughing and cheering with her. The knowing laughter grew louder when she gestured toward her husband, Harvard law professor Bruce Mann, and said in reference to her long-ago teen love, “Not with this guy.” Warren continued with the riff, “And then I got married, but not to this guy.” She spoke of dropping out of college at 19 and discovering that she could only resume her education at a commuter school, the University of Houston, which charged a mere $50 a semester in the 1960s. “I knew it was my one last chance,” she said. “I hung on for dear life. I finished my four-year diploma and I became a special-needs teacher. I have lived my dream.” At the word “dream,” Warren’s audience broke into applause.

On an intellectual level, Warren’s story buttresses a key theme of her broader policy agenda, reminding her listeners that a half-century ago, unlike today, America provided opportunities to strivers—whether it was the possibility of supporting a family on a minimum-wage job or attending a four-year college without going into lifelong debt. But reading her stump speech as a purely didactic performance to carry her issues across to a mass public glosses over a key aspect of her political persona. Unlike almost all her rivals, Warren tells a tale that mirrors the struggles of many Democrats, especially women. In Peterborough, New Hampshire, in July, Warren added a wrinkle to the story that could easily serve as the plot of a feminist novel: “My first marriage doesn’t work out. I think my first husband and I were both a little shocked to find out who I turned out to be.” This kind of emotional honesty may help explain (despite the media’s tendency to place a greater premium on ideology than personal appeal in sorting out the Democratic field) why, at Warren events in Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina, I encountered many more 2016 supporters of Hillary Clinton than of Sanders.

Analyzing a Warren stump speech without making reference to substance is akin to writing a biography of Marie Curie without mentioning radioactivity. The former law professor’s analysis of the inequities at the heart of the American economy serves as the rationale for her candidacy as much as “Barack and me” explains Biden’s third quest for the White House.

In Iowa and New Hampshire—and most points in between—Warren has distilled the argument at the core of her campaign to a few sentences. “It’s whose side government’s on,” she said in Waterloo, perhaps consciously evoking an old-time labor song. “We have a government that works great, that works fabulously, for giant drug companies,” Warren continued, “but not for people who are trying to get a prescription filled.” She then offered a similarly structured riff: “We have a government that works great for giant oil companies that want to drill everywhere—just not for the rest of us who see climate change bearing down upon us.”

All of this set up her logical conclusion and an enthusiastic round of applause: “When you’ve got a government that works great for those with money, and it’s not working so good for anyone else, that is corruption pure and simple. And we need to call it out for what it is.”

Since the presidency of Woodrow Wilson, the White House’s only Ph.D., the upper echelons of American politics have been woefully short of serious academics. Four-term New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a Harvard intellectual who never lost his faculty club manner, shimmers as a rare exception. (Newt Gingrich does boast a Ph.D., but it is difficult to regard him as a serious thinker—or truly as a serious anything.) That’s why it is so unusual to watch a candidate like Warren revel in her own wonkiness. The campaign even sells $30 unisex T-shirts bearing the legend “Warren Has a Plan for That.”

In Peterborough, Warren announced, “I have the biggest anti-corruption plan since Watergate.” She then ticked off what she called “a sampler” that ranged from “end lobbying as we know it” to “block the revolving door between Wall Street and Washington.” After she rattled off a few examples, Warren said with palpable enthusiasm in her voice, “I could do these all day long.” That bubbly moment triggered affectionate laughter.

There are two unalterable orthodoxies of politics. Every losing campaign is filled with aides peddling stories under the rubric, “If only the candidate had listened to me.” And with every winning campaign, said David Axelrod, “there is a lot of discussion that they’re inventing the wheel.”

Although they may now seem like the collective outcome of a carefully executed day-by-day plan, many of the striking aspects of the Warren campaign (the blizzard of footnoted position papers; the ban on high-roller fund-raisers; and the decision to, at least temporarily, avoid hiring an outside pollster and media consultant) were fairly ad hoc and incremental. They were also, Warren watchers agree, a reflection of the candidate’s own determined and focused character. As a Warren insider put it, “There was never a Saul on the road to Damascus moment” in the campaign’s first strategy sessions.

The most telling decision made at the outset was the heavy initial investment in staffers, particularly in Iowa and New Hampshire. This was not by any means a paint-by-numbers move; rival campaigns, such as those of Kamala Harris and Pete Buttigieg, waited until June to go on a hiring binge in Iowa. As a result, the media consensus is that Warren boasts the best ground game in the opening-gun states, which can make a significant difference in a close race. As top strategist Joe Rospars explained, “From a budgetary perspective, it’s fair to say that decisions about building your organization are because you can add media at the end. But you can’t go back and add organization.”

By late July, the Warren campaign had released 29 position papers on topics ranging from banning private prisons to doubling the size of the Foreign Service. The pace of this paper chase and the level of policy detail and supporting material are unprecedented since I began covering presidential politics in 1980.

Traditionally, at this stage of the campaign, candidates—even those who draw praise for their issue-oriented rigor—might have delivered a few meaty policy speeches, published a staff-written global overview in Foreign Affairs, and issued a handful of fact sheets outlining the contours of their approach to the federal budget and taxes. Bill Clinton only published his campaign policy book, Putting People First, in September 1992, just two months before the election. Even then, the book was much stronger in assertion than backup documentation, and its 232-page length was padded with the text of Clinton’s convention acceptance speech.

When the Warren campaign in January released its Ur-document—a proposed $2.75 trillion wealth tax over ten years—few in the campaign expected that this would serve as a template for the entire run. As campaign issue adviser Bharat Ramamurti, a veteran of Warren’s Senate staff, explained, “To get stuff past her, we need a lot of data and details on it. If we said, ‘We have a wealth tax that will raise between $2.5 and $3 trillion,’ she would say, ‘I want to know the methodology you’re using for that. I want to know exactly what data sets you’re using to determine how much wealth there is in the top 0.1 percent. I want to understand year to year what happens to the amount of revenue we generate.’”

On the key left-primary issue of the brewing student debt crisis, you can see Warren’s own penchant for policy nuance in high relief. That’s especially the case when you size up Warren’s proposals alongside Bernie Sanders’s broad-brush pledge to wipe out the existing student loan system, establish free college for all, and work out most of the details later.

On his web site, the Vermont independent pledges, a bit redundantly, to “cancel the entire $1.6 trillion in outstanding student debt for the 45 million borrowers who are weighed down by the crushing burden of student debt.” That means that everyone would benefit—from a struggling nurse who graduated from a two-year public institution to a fledgling investment banker from an affluent family who borrowed heavily to attend Princeton. In contrast, Warren’s plan caps student debt cancellation at $50,000 and gradually phases out the benefits for those earning between $100,000 and $250,000—thereby lessening the subsidy for upper-income college graduates.

To be sure, the policy divide between Sanders and Warren on this issue should not be exaggerated. All campaign policy documents—even those as rigorous as Warren’s—are tentative drafts that will be reworked from scratch if the candidate is elected president. But looking closely at issue papers like Warren’s student loan proposal offers a window into how her mind works. As Ramamurti put it, “She is an academic at heart. And data undergirds everything she does. When she puts out a new policy idea, doing it with rigor is important to her.”

And even the white-paper–enchanted Warren had not yet at the end of July filled in all the blank pages in her issue portfolio. During the first Democratic primary debate, she endorsed the elimination of private health insurance under Medicare for All, but she has yet to offer her own plan for achieving universal coverage. In the crucial sphere of foreign policy—where presidents operate with the greatest latitude—Warren is still an often-unknown quantity. In an early 2019 Foreign Affairs article, Warren waxed dovish: “It’s time to seriously review the country’s military commitments overseas, and that includes bringing U.S. troops home from Afghanistan and Iraq.” But she has yet to offer a full plan outlining how she would respond to humanitarian crises like the 1994 genocide in Rwanda and Syrian President Bashir Assad waging vicious warfare against his own people. In similar fashion, Warren—who joined the Senate Armed Services Committee after the 2016 election and enjoyed overseas trips with John McCain—had not, at press time, produced her own detailed policy paper for cutting the Pentagon budget.

The town hall in Peterborough, across the street from an antiques shop, is an early–twentieth-century red brick structure that feels like it rang with patriotic fervor during the Revolutionary War. With a stage and a balcony, it is one of those New Hampshire sights that TV cameras and political advance teams love—it’s a vivid symbol of the live-free-or-die traditions that animate the political rhetoric of the Granite State during the first primary.

On a Monday afternoon in July, Elizabeth Warren filled the building, which has a crowd capacity of 500, to the rafters. Another 150 would-be supporters waited on the sidewalk to be rewarded with an impromptu two-minute greeting from the candidate and an audio feed of the town meeting. The crowd was overwhelmingly white and seemingly affluent, as Warren, wearing an orange sweater, paced the stage in front of an oversize American flag.

The senator from the neighboring state had been speaking and answering questions for more than an hour. But Warren had one final message—one last staple of her stump speech—before she left the stage. She spoke about the economic battles that had defined her career and how she had been told again and again, “Washington’s too hard. Try it somewhere else.”

Using repetition like a rapier, this Harvard law professor who had risen to the Senate after a long tour through the unglamorous world of bankruptcy law and career-and-marital back-switching, talked of how the suffragettes had been told, “It’s too hard, give up now.” How the early labor organizers and the foot soldiers in the civil rights movement had been told, “Not going to happen. Give up and move on.”

Warren—sounding like the La Pasionaria of the primaries—declared, “But nobody gave up. They organized. They built a grassroots movement. They persisted.” At the word “persisted”—a reference to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s rebuke to Warren for denouncing the segregationist past of Jeff Sessions, Donald Trump’s first attorney general—the room broke into such loud cheers that you could barely hear the candidate’s final words: “This is our chance to change the course of American history.”

But unlike a Bernie Sanders crowd, say, there was little sense that these L.L. Bean-clad revolutionaries really want to go to the barricades. They just like Elizabeth Warren—her passion, her intellect, and her lack of artifice. And in a crowded Democratic primary field, without a clear front-runner firmly in place, that may well be enough.

* A previous version of this story incorrectly referred to “the GOP majority” in the Senate in 2011. In fact, the GOP was in the minority.