In the Soviet Union, every literary work was a political statement, whether the writer liked it or not. Soviet censorship allowed some room for negotiation, but outside the USSR, official and dissident literature were perceived as polar opposites. This stark distinction imbued Soviet-era literature with a gratifyingly Manichaean quality, and Western readers became enamored of the stories of books that had escaped to liberty while their authors remained at the mercy of the Soviet authorities. The more strenuous the Soviet efforts to suppress a work, the greater its frisson of the forbidden. Meanwhile, literature that had been published in the Soviet Union was most often ignored. This left Western readers with an imperfect understanding of the many authors who resorted to illicit publication only at desperate moments.

Vasily Grossman is best known in the West for his World War II novel Life and Fate, which he wrote in the 1950s. Grossman’s attempts to publish his novel in the Soviet Union ended with the manuscript’s famous “arrest” in 1961, one of the only cases when the KGB seized a manuscript but not its author. Fortunately, two of Grossman’s friends had hidden copies. Grossman died of cancer in 1964, in despair over the suppression of his masterpiece. The dissident satirist Vladimir Voinovich arranged to have microfilm of Life and Fate smuggled abroad in 1975, but it took years to find a publisher. By then, the Orthodox Russian nationalist Solzhenitsyn was the new big thing in Soviet dissidence; Grossman’s Jewish themes had a narrower appeal. The novel was published at last in 1980, in Switzerland, due to the tireless efforts of a handful of mostly Jewish Russophone writers and intellectuals, and it eventually became a classic.

Running to nearly 900 pages, this monumental work traces the wartime experiences of an extended family, the Shaposhnikovs, their spouses, lovers, friends, and colleagues, and figures from various spheres of Soviet life. Several key characters end up in Nazi concentration camps or in the Gulag; the novel’s juxtaposition of the German and Soviet systems brought Grossman admiration in the West, where he was cast as a visionary anti-totalitarian. This is a reductive understanding of an author who not only cherished individual subjectivity, but also valorized the transcendent power of collective action. Grossman’s anger at Soviet abuses was motivated in part by grief over the betrayal of revolutionary ideals. Nevertheless, his work has been touted as a warning against radical visions of all kinds, used to support the argument that communism and fascism are merely two sides of the same coin.

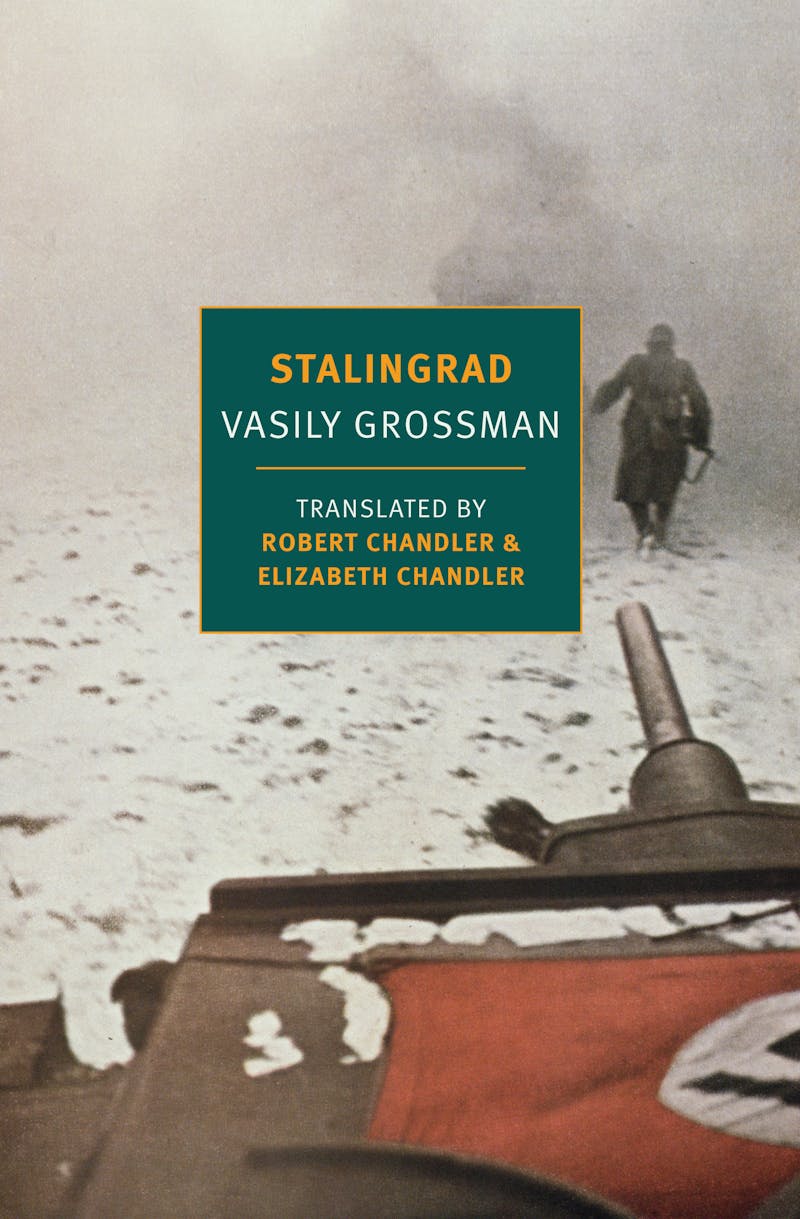

Yet Life and Fate was only the second half of an epic work that started with Stalingrad, written in the 1940s and all but forgotten until recently. Only now is the novel available in English for the first time, in a version edited by Robert Chandler and Yury Bit-Yunan and beautifully translated by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler. Its misfortunes are not difficult to explain: Unlike Life and Fate, Stalingrad was published in the Soviet Union under Stalin and gained a reputation as Stalinist hackwork. Even Grossman’s primary English-language translator, Robert Chandler, confesses that he resisted reading Stalingrad for many years, only taking the plunge at the urging of historian Jochen Hellbeck.

There is also the problem of subject matter. Life and Fate’s success reflects the insatiable Western appetite for literature about Soviet crimes; there is far less enthusiasm for stories of Soviet victory. The terrifying, astonishing source material for Stalingrad is the Battle of Stalingrad, in which between 1.25 million and 1.8 million people were killed. This sacrifice is still a point of pride in Russia today, where it is commemorated, rightly, as a turning point in World War II. Stalingrad documents horrors, but it also celebrates the choice to give up one’s life for Communist ideals and freedom from fascism, to consciously reject the natural impulse for self-preservation.

Stalingrad shows a writer who was a less adamant critic of the Soviet project than a reader of Life and Fate might think. It also presents some of the finest examples of Grossman’s prose, an argument to read him not only as a fervent critic of totalitarianism, but as a deeply compassionate writer with an extraordinary gift for portraying psychological complexity and sensory detail.

Born in 1905 to Jewish parents in the Ukrainian town of Berdichev, Grossman was educated as a chemical engineer and worked in industrial settings in the Donbass before becoming a full-time writer in the 1930s. When war broke out, he volunteered to fight, but he was rejected for health reasons. Instead he was assigned to work as a frontline correspondent for Red Star, the military paper, collecting a vast quantity of information from personal interviews (he was renowned for his ability to coax an interview out of absolutely anyone), military reports, and his own acute observations of the world around him. His articles were widely admired, and soldiers read them at the front.

After the German defeat at Stalingrad, Grossman accompanied the Red Army to Ukraine and Poland, where he learned about the fate of the Eastern European Jews, including his own beloved mother. His 1943 story “The Old Teacher,” which appeared in a leading Soviet journal, and his article “Ukraine Without Jews,” published in Yiddish by the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, were among the first printed accounts of the Holocaust. His 1944 “The Hell of Treblinka” was the first article ever written about a Nazi camp, and was used as evidence in the Nuremberg trials. From 1943 to 1946, Grossman worked with fellow Jewish Soviet writer Ilya Ehrenburg on The Black Book of Soviet Jewry, which was commissioned by the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee to document the killing of Eastern Europe’s Jews; this work was never published in the Soviet Union, which chose to pretend that all of its peoples had suffered equally during the war.

Meanwhile, Grossman was hard at work on Stalingrad. This huge, sweeping novel begins the stories of many of the characters from Life and Fate, including the Shaposhnikov family. Through the eyes of Grossman’s wide-ranging cast, we experience June 22, 1941, the day Germany invaded the USSR and transformed Soviet life forever. Some of his protagonists are officers or privates in the army; others contribute their scientific or managerial skills to wartime industry, or work at hospitals or orphanages; many are forced to flee east, further from the front lines. We see people killed, captured, or wounded by the Germans, struggling to keep their besieged city running, fearing for their loved ones, receiving devastating news, and trying to maintain a semblance of normal life, against all odds.

In 1952, the literary journal Novy Mir began publishing the novel, which editors had retitled For a Just Cause. It was greeted with critical and popular enthusiasm and was even nominated by the Writers’ Union for a Stalin Prize. But in the month the first installment appeared, members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were put on trial, to be executed the following month. This was the beginning of Stalin’s “anti-cosmopolitan” campaign, which soon escalated into the “Doctors’ Plot,” a paranoid fantasy about a conspiracy by Jewish doctors to poison Stalin and other leaders. Grossman, a Jewish author, was denounced in the press and by his editors. His career, and likely his life, were saved by Stalin’s death in March 1953. In 1956, after the beginning of de-Stalinization, the novel was censored and published once again, this time removing positive references to Stalin.

Censorship shaped Stalingrad in more subtle ways too. While working on the novel, Grossman was engaged in a continuous struggle with editors who wanted to redact the politically dangerous Jewish theme, and he had to find more and more indirect ways to approach his subject. You can see this writing between the lines in the most poignant plotline in Stalingrad, the story of Ludmila Shaposhnikova’s husband, a Jewish nuclear physicist named Viktor Shtrum—clearly modeled on his author—and his mother, who remained in her Ukrainian hometown after the outbreak of war. As he waits for news of her, Viktor has a prophetic dream about a room whose inhabitants have left all of a sudden, in the middle of the night. Though he doesn’t spell it out, we know—as Grossman’s contemporaries would have known—that Viktor’s mother is almost certainly dead. His dream is not only about his mother; it is a premonition of the pillaged homes of millions of Eastern European Jews, the loss of a whole civilization.

Soon Viktor receives a final letter from his mother. We see what he does after reading it, but we do not have access to its contents. Robert Chandler believes that “rather than toning her letter down to make it acceptable, [Grossman] took a conscious decision simply to leave a blank space, to replace her letter by an explicit, audible silence.” This blank space is devastating in its own way, evoking not only Nazi crimes but also the postwar persecution of Soviet Jews and their erasure from public memory.

Only in Life and Fate do we find out what the letter said. By then, Grossman was no longer willing to make any concessions to censorship, and this later novel is among the most devastating accounts of the Holocaust ever written. There Viktor’s mother’s letter appears in full, detailing her feelings as the Germans arrive, as her neighbors expel her from her room and seize her possessions, as she is sent to the Jewish ghetto, as she hears that Jewish prisoners are being forced to dig a deep ditch outside town, as she prepares for death. She tells her son that the Germans have reminded her of what she had forgotten—that she is a Jew—and her letter makes Viktor, too, come to fully understand his own vulnerability, even in the relative safety of Soviet territory.

War and Peace towered above all other novels for Russians during World War II, and it inspired Stalingrad and Life and Fate, with their extended family of protagonists and their philosophical and historical digressions. Grossman admired Tolstoy’s lucid, approachable literary style, and, like Tolstoy, he can paint a vivid picture of almost any sort of person. The opening chapters of Stalingrad move from an awkward encounter between Hitler and Mussolini to the heartrending moment when a Russian villager receives his call-up papers and worries that he can’t leave his family enough firewood to see them through the winter.

One marked difference between Grossman and Tolstoy is in their depiction of women. Grossman offers convincing portraits of women of all kinds—and there were many kinds of women in the Soviet Union, especially in wartime. Tolstoy could never have imagined Alexandra Shaposhnikova, an elderly intellectual, passionate about her job monitoring the air quality of industrial workplaces, or Sofya Levinton, a never-married, middle-aged surgeon and Red Army major who spent years on scientific expeditions to Central Asia. For Grossman, a woman’s capacity to be a principal character does not end with her reproductive years.

Grossman’s skill at characterization extends beyond the world of the human. A worn hand mirror in which a girl admires herself, a toddler’s faded trousers, “wooden spoons with edges nibbled away by impatient childish teeth” seem to come alive as they register the end of the home life that they once furnished. As Stalingrad is bombed, Grossman writes, “Buildings began to die, just as people die. Tall, thin houses toppled to one side, killed on the spot; stockier, sturdier houses trembled and swayed, their chests and bellies gashed open and exposing what had always been hidden from view.” Meanwhile, people imagine themselves as objects helpless against the momentum of history. As he prepares to go to war, one man experiences “the horror that a splinter of wood might feel if it suddenly realized that it was not moving of its own accord past the river’s green banks but was being carried by the insuperable power of the water.”

Stalingrad is an extreme case of a “loose baggy monster,” but the lesser sections—for example, chapters on a wartime coal mine, added at the behest of editors—fade from memory quickly, while Grossman’s exquisite sensory details linger. You feel the sharpened perceptions of people who know they may be saying goodbye to their homes, their land, their families for the last time; that this may be their last meal, their last kiss, their last conversation. You feel the joy the characters take, in a time of frequent hunger, in a bag of white flour or a briefcase full of butter, sturgeon, and caviar. And you take in the smell of different substances as they burn, the way explosions sound when they’re muffled and blurred by bunker walls.

Just before Viktor reads his mother’s final letter, which has passed through many hands, and which he briefly mistook for a chocolate bar, he goes out into a garden after it has rained:

The moist air was warm and clean; every strawberry leaf, every leaf on every tree, was adorned with a drop of water—and each of these drops was a little egg, ready to release a tiny fish, a glint of sunlight, and Viktor felt that somewhere in the depth of his own breast shone an equally perfect raindrop, an equally brilliant little fish, and he walked about the garden, marveling at the great good that had come his way: life on this earth as a human being.

The next morning, he pulls away the blackout curtain and looks again at the garden. His anguish is only evident in his thought that the dew looks like shattered glass. He expects to be transformed forever by the terrible content of the letter, but when he looks at himself in the mirror, he sees no change. Feeling hungry, he eats a piece of bread. Life goes on.

The beauties and pleasures of the natural world help inspire an almost indomitable will to live; the destruction of the earth is one of the most terrifying dangers posed by war. Grossman describes, in remarkable detail, how birds, rats, dogs, and horses flee from Stalingrad as it burns. Late in the novel, a young Ukrainian refugee who has lost her mind sits “gazing with mad eyes at the dense yellow dust whirling over the steppe,” shouting, “The earth is on fire!...The sky is on fire!” Over the course of human history, many people have wandered, hungry and homeless, across continents. But is it possible to survive a world set on fire?

Like so much of the Soviet-era literature acclaimed in the West, Grossman’s work is celebrated as a warning of the dangers of revolutionary aspirations. In the decades since they’ve become available to English speakers, his novels have been read as cautionary tales of a world comfortingly distant from American or British readers. But today, the camps, the floods of refugees, the annihilation of cities and nature that Grossman documented seem much closer to our own reality. Stalingrad is, among other things, a testament to the human capacity to rally the bravery, altruism, and resilience needed to bring the world back from the brink of destruction.