Fact and fiction are interminably wound up in Natalia Ginzburg’s novels. In a preface to an early novel, Voices in the Evening, she clarified that the characters in the story “are not alive, nor have ever lived, in any part of the world.” Family Lexicon, the most autobiographical of Ginzburg’s books, was to be read as a novel though the story was real. “I haven’t made up a thing,” she wrote, “and each time I found myself slipping into my long-held habits as a novelist and made something up, I was quickly compelled to destroy the invention.” The habit began in her childhood, we learn in Family Lexicon. Young Natalia often had to reconcile the things her parents told her with the things she could see happening in front of her, so that “truth and lies became all mixed up for me.”

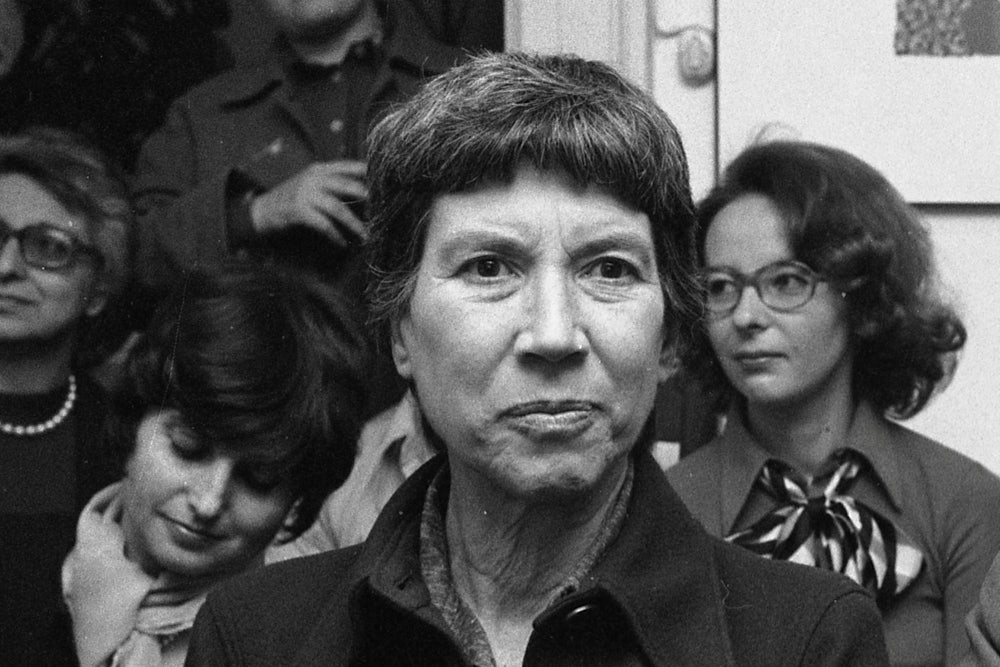

Truth and lies were, of course, bound to be mixed up under fascism. Ginzburg’s father was a Triestine Jew, and though as a biologist he wasn’t exactly invested in politics, he would frequently put up socialist friends forced to go underground in Mussolini’s Italy. In 1934, he was arrested with his eldest son for their alleged involvement in an anti-fascist conspiracy; another son managed to escape and cross the border into Switzerland. As the youngest of five, Natalia was insulated from the turbulence at home, but a few years later, just before World War II broke out, she married Leone Ginzburg, a family friend who had been arrested as part of the same conspiracy as her father. War ushered in a different order of reality. Her parents migrated to Belgium after her father lost his job as a professor in Turin. They gradually made their way back after the German invasion and ended up in Florence in disguise. Leone, Natalia, and their two children were exiled to the Abruzzi, where she wrote her first novel, The Road to the City, published under a pseudonym. Shortly after the Italian armistice in 1943, the couple moved to Rome and Leone was arrested for plotting against the occupying German troops. He died two months later in prison.

Wars, deaths, suffering women, and families and their discontents: These are Ginzburg’s abiding themes. But she approaches them with a stoic reticence. Her books seem all the more profound for what they leave out; and this is true even for a “real” story like Family Lexicon. The narrator of the novel, Natalia, is concise to a fault about everything that directly concerns herself—even her husband’s death:

Arriving in Rome, I breathed a sigh of relief believing that a happy period was about to begin for us. I didn’t have any reason to believe this, but I did. We had a place to stay near the Piazza Bologna. Leone was the editor of a clandestine paper and was never home. They arrested him twenty days after our arrival and I never saw him again.

That her husband was tortured to death by the Nazis is something we must infer from that terse “I never saw him again.” These omissions might appear deliberate to her Italian readers who know more of the context, but in the English-speaking world, Ginzburg’s writing has been time and again called “eccentric.” Her choices have been rarely understood to be artistic. A new translation of Family Lexicon was published in 2017, followed by the reissue of The Little Virtues, her collection of essays. Both books perpetuated an image of Ginzburg as endearingly provincial—a writer of funny, charming, but ultimately slight, portraits. Her style takes some time to get used to: much is meant by saying little. Over the years, English readers have interpreted her restraint, her carefulness about making things up, for a quirky interest in surfaces.

To read Ginzburg this way is to overlook not just the impact she had on the postwar literary landscape in Italy, but also her enormous range as both a writer and a public intellectual. She didn’t just obliquely chronicle her family’s suffering during Mussolini’s reign; all her life she remained politically and socially involved. Her activism even culminated in her tenure as an independent member of the Italian Parliament. Her books reflect the radical clarity of a generation that had seen tyranny very early in their lives. “We shall not get over this war,” she once wrote. “It is useless to try.”

New translations of two novels present a more complete image. The Dry Heart, Ginzburg’s second novel, begins with a blunt confession: The narrator has just killed her husband, Alberto. He had been packing to go away on a trip when she entered his study and “shot him between the eyes.” She leaves the body in the room and heads out for a walk. Once inside a park in the neighborhood, she sits down on a bench and takes off her gloves: “Then I slipped off my wedding ring and put it in my pocket.”

The tone here is thriller-like, but simultaneously tinged with a riper chord of despair. The narrator, unnamed throughout, has no desire to escape and nowhere to escape to in any case. Instead she seems to realize that her coolness towards her crime mirrors, in a strange way, Alberto’s deeper lack of passion for her while alive: murder becomes the ultimate proof of marriage. He had never been in love with her, and she used to flinch in disgust when she imagined them having sex. Yet she had fallen for him, while waiting for him in the evenings to visit: “I married him because I wanted to know where he was.”

Living together meant that he always knew where she was—at home. She quits her job to move in with him, while he remains at large, unattached, frequently disappearing for days on trips with an old flame. The narrator had known about the other woman before marriage. Insofar as she felt wronged, it is not so much because she hadn’t expected Alberto to cheat; it is because he lacks the courage to anchor himself to anything definite, preferring to drift through life instead like “a cork bobbing on the surface of the sea”:

Once Alberto told me he had never done anything in earnest. He knew how to draw, but he was not a painter; he played a piano without playing it well; he was a lawyer but he did not have to work for a living and it didn’t make much difference whether he turned up at his office or not.

When the couple has a child, Alberto moves out, unable to commit into being either a husband or a lover. But then the baby dies, and he moves back to help the narrator recuperate. Inevitably she falls in love with him again. She realizes that, even after the loss of a child, she remains more afraid of Alberto going away, and how lucky other women who have nothing to fear are. “How easy life is, I thought, for women who are not afraid of a man.” Seen in this light, her crime is no more than the result of her eventual exhaustion. At last she feels tired, not necessarily of Alberto or their marriage—but of feeling afraid.

In Ginzburg’s telling, the crime procedural becomes a cri de coeur against marriage. Compared to the sheer desperation of the narrator’s frame of mind, the details of the murder feel incidental, unimportant. The effect is of reading something almost obscenely personal, and perhaps for that reason, scintillatingly political. Alberto’s refusal to obligate himself in any way can at times seem like an extreme reaction to fascism’s doubling down on hierarchies and obligations, but it is also hard to ascribe any subconscious motive to someone so routinely afraid of owning up to his true self, someone whose aversion to making any major choices can seem just as oppressive as the worst of them.

The male characters in Happiness, As Such, originally published in 1973, are again representative of a fundamentally life-denying irresponsibility. There is Michele, a dabbling painter who has run away from Italy to England, possibly to escape arrest for his political links; there is Michele’s father, a professional painter, dying of a stomach ulcer, keen to bequeath a tower he bought in the countryside to his wayward son; there is Michele’s friend, Osvaldo, who spends his days running a bookshop and running errands for Michele in Rome. The novel plays out in a sequence of letters sent to Michele by his mother, Adriana; his sister, Angelica; his ex-girlfriend, Mara, who is pregnant with a child that might be Michele’s. It is the winter of 1971 in Italy, when fascist spies are still infiltrating artist groups to report those with communist sympathies. The men are either far away, or self-involved and useless: The women have to fend for themselves.

The characters of Happiness, As Such seem united in their credo of bleak pragmatism. They skip over pricklier emotions to avoid an impasse. And yet the story feels fully realized in moments when characters have to reckon with their feelings in unexpected ways. Angelica is reasonable about her father’s death until she remembers a song he used to hum while painting when she was a child; Adriana is in love with someone else, but considers moving in with her ex-husband in his last days; Mara’s baby strangely becomes an excuse for everyone else to make allowances for Michele. The novel is a more jaded counterpart to Family Lexicon, in which humor helped characters cope with the horrors of the war. In Happiness, As Such, the political stakes are significantly less, but the underlying pain and anguish feel just as dire. The story may not be real, but the problems are.

In an essay last year, Rachel Cusk praised Ginzburg for understanding that stories aren’t real. “Ginzburg separates the concept of storytelling from the concept of the self,” Cusk wrote, “and in doing so makes a great stride towards a more truthful representation of reality.” But Ginzburg is as interested as any other novelist in telling stories—just that she tells them from a point of view different than her own. What impels her forward is the voice: free, pellucid, almost always first-person, interested not in the long view but in the here and now. Her novels stand out for their brazen disregard for omniscience, manifested in her avoidance of the close third-person. Even in a populated novel like Happiness, As Such, she’d rather employ an array of first-person accounts—through the letters—to arrive at a consensus on reality, than maintain an authorial distance. This also means the writer must become each of her characters in turn—mother, murderer, husband, friend—and allow them their chance to speak.

“My vocation has always rejected me,” Ginzburg wrote in The Little Virtues. “It does not want to know about me.” Having lived through the repercussions of a single point of view under Mussolini, the art of storytelling was, for her, self-effacing and democratic. The result is rewarding for the reader but, as the prefaces she wrote to her novels suggest, not so much for Ginzburg. Her emphasis on distinguishing fact from fiction must have at least been partly a note to self, for someone who wrote so perilously from inside the skins of her characters. Perhaps, even in the best of times, Ginzburg was at risk. Truth and lies were always on the verge of being mixed up.