When I read mainstream political commentary, I often think of the awkward gyrating Elaine used to do on Seinfeld, flapping her limbs in all directions in an incompetent, and yet totally confident, imitation of what dancing is supposed to look like. Political pundits are engaged in a similar dance. Convinced of their abilities, they mimic certain words and phrases they associate with skillful political commentary, all without realizing how clumsy they must appear.

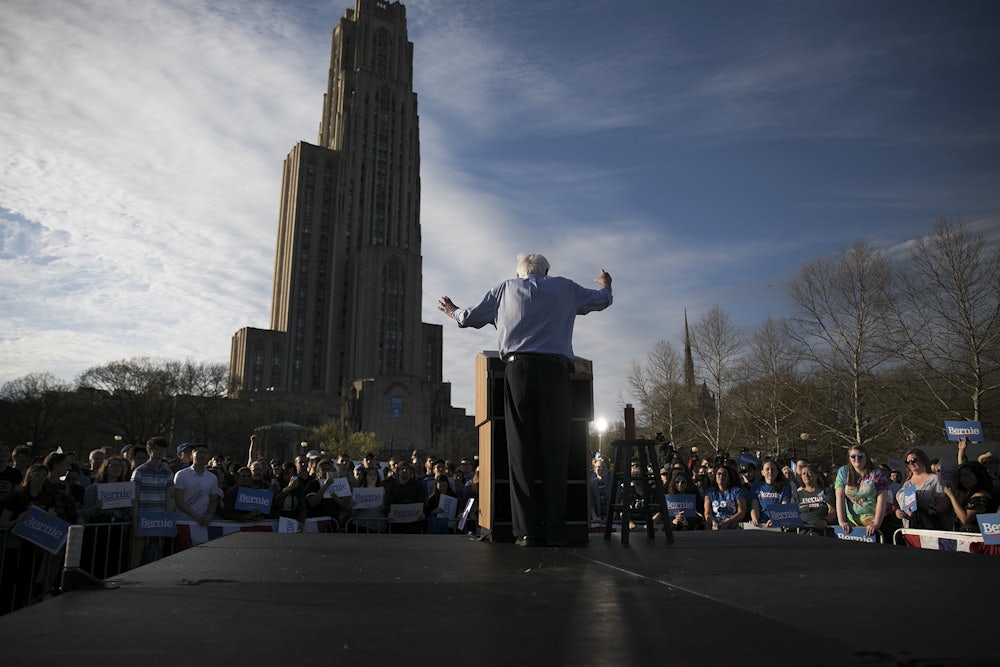

One word journalists frequently stumble over is “populist.” It was coined in the 1890s, when Kansas Democrat David Overmyer needed a convenient noun to identify members of the new People’s Party. Then, as now, populists claimed to act in the name of ordinary Americans against an exploitative elite. When Bernie Sanders denounces the “billionaire class,” for example, he speaks for “the people.” Likewise, when Donald Trump addresses the “forgotten man and woman,” he invokes a community of ordinary, excluded people—and, implicitly, those who do the excluding. The more the word is used, however, the more meaningless it feels.

Today, a populist might be socialist or conservative, tolerant or nativist, egalitarian or racist (Elizabeth Warren, Ross Perot, and Hugo Chávez have all earned the moniker). It can describe a coherent political program, or a mere affectation, such as dropping one’s g’s and conspicuously owning a pickup truck. Reporters, eager to appear neutral, have taken to deploying the word as a euphemism for the resurgent racist right; when USA Today calls the alt-right a vehicle for “racism, populism, and white nationalism,” for example, it’s not clear what these terms mean or how they differ. Some foreign-policy pundits explain the success of Trumpian populism with a xenophobic metaphor of contagion—as if “our democracy” has caught an authoritarian bug from some unvaccinated place like Russia or Venezuela. And just as the rural populists of the nineteenth century were mocked as irrational “cranks” and “calamity howlers,” modern populists of all stripes always seem to be “angry” or “unhinged.” For the Washington Post columnist Jennifer Rubin, Sanders is “prickly,” seducing voters with the “rhetoric of an angry populist not actually grounded in reality.”

Focusing on populism as a mood or as a virus implies that it is all rhetoric—as if the anger of “the people” is something suspicious, a phantasm summoned by crude and dishonest demagogues. Left out is an important question. If American elites really do act like vampiric idlers, shouldn’t the rest of us be a bit “prickly”? Besides, what democratic politics worthy of the name doesn’t mobilize “the people”? If an appeal to a broadly defined common people struggling against an out-of-touch elite is populist, then the Declaration of Independence is a populist document par excellence.

The trouble starts when people assume populism is, as Robert S. Jansen of the University of Michigan puts it, “a thing”—a particular ideology or style of governance—rather than a set of practices that partisans use to mobilize the people against an elite. Populism is something you do, not something you are, and even levelheaded centrists do it. The real question, then, isn’t whether a candidate or thinker is populist, but what the consequences of his or her populism are. Whose version of “the people” do you want to empower? And whose version of “the elite” do you seek to suppress?