Last spring, 28 Tory hardliners unleashed another round of havoc on British politics, refusing to vote for Prime Minister Theresa May’s compromise Brexit plan and paving the way for her replacement by Britain’s Trump variant, Boris Johnson. The group of hardcore Euroskeptics dubbed themselves “Spartans” for their singleminded willingness to hold the line, to sacrifice anything in obedience to their convictions. British news outlets ran with the moniker; the Daily Mail praised the group’s efforts to sink its own government as “The last stand of the Spartans.”

Last August, Stewart Rhodes, the founder of the right-wing anti-government and anti-immigration American militia group Oath Keepers, appeared on conspiracy media outlet Infowars to announce the launch of “Spartan training groups” that would prepare armed Americans to defend the country from the “violent left.” The Oath Keepers’ website also invokes Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Self Reliance,” which exhorts readers to “hear the whistle of a Spartan fife”—a nod to references in both Thucydides and Plutarch that the Spartans used the double-reeded, oboe-like aulos to keep in step while marching to battle.

Ancient Sparta’s influence is all around us, providing a litany of patron saints for spectacular last stands. There’s a word for this mania in Western cultures: laconophilia, taken from Laconia, the region the Spartans hailed from. Most of us have never heard of laconophilia, even as we live in a world so dramatically shaped by it, but it has a hand in everything from the French Revolution to the British educational system to the Ivy League to the Israeli Kibbutz movement. There are at least 39 municipalities named after Sparta in America alone, and I gave up counting the number of American and Canadian high school sports teams named “the Spartans” once I hit 100 (Michigan State and San Jose State, both NCAA Division I teams, are also named after them). The very word spartan transcends the historical city-state to which it once referred; it can now refer to anyone or anything marked by strict self-denial, frugality, or the avoidance of comfort—reflecting the legend of the Spartans, rather than who they actually were.

That the legend has little to do with the real Spartans would be an academic point, but this myth has now turned malignant, with laconophilia taking on darker and ever more dangerous tones. The stylized Corinthian helmet worn by King Leonidas in 300, the 2006 hit movie mythologizing the Spartan role at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 B.C.E., is now most often seen on T-shirts, flags, and bumper stickers above the Greek words “ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ,” or molon labe, which translates to “come and take them,” the Spartan king’s apocryphal, defiant response to Persian ruler Xerxes’s demand that the Greeks surrender their arms. For pro-gun advocates, molon labe has become a rallying cry of resistance to perceived government overreach.

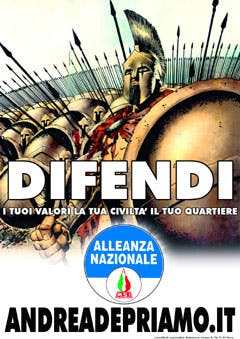

This paranoid vision of a government coming to take your guns, or an alien invader coming to take your culture, has led to more troubling invocations of the Spartan myth, and not just in Anglophone countries. The Greek neo-fascist party Golden Dawn gathers each year at Thermopylae, lighting torches and chanting anti-immigrant nationalist slogans. “The message of Leonidas—molon labe (come and get it)—is as timely today as ever for everything tormenting Greece,” Golden Dawn higher-up Eleftherios Synadinos, a former special forces general and a member of the European Parliament, told the assembled partisans there in 2015, just before the crowd broke out into chants of “People! Army! Nationalism!” In Italy, Alleanza Nazionale, a rebranding of the fascist party Movimento Sociale Italiano after its 1995 dissolution, has used Spartan imagery reminiscent of 300 in propaganda posters captioned “Defend your values, your civilization, your district.”

The metastasis of Sparta worship in the “fake news” age offers an object lesson in how to rewrite the history of a people and a culture, pressing them into the service of hard-line political movements marked by racism, nationalism, and tyranny. How did the Spartans, who ceased to be a real political force more than 2,100 years ago, come to hold such a widespread, and increasingly pernicious, influence on contemporary society?

Browse any online bookstore using the search term “Spartan,” and you’ll find the vast majority of the results are not works of history, but of self-help: The Spartan Way: Eat Better, Train Better, Think Better, Be Better (not to be confused with The Spartan Way: What Modern Men Can Learn from Ancient Warriors); Self Discipline: The Spartan and Special Operations Way to Mastering Yourself (not to be confused with Mental Toughness Mastery: Spartan Self Discipline and Intermittent Fasting); and Spartan Fit!: 30 Days. Transform Your Mind. Transform Your Body. Commit to Grit. (not to be confused with Spartan Up!: A Take-No-Prisoners Guide to Overcoming Obstacles and Achieving Peak Performance in Life).

The Spartan legend trades on our deep-seated sense of inadequacy. It mines our insecurities that we aren’t strong enough, hard enough, disciplined enough: If we want our sports teams to bring home the trophy, if we want to win a fight, if we want the grit and sheer toughness to triumph at life, we would do well to emulate the Spartans.

The problem is, the Spartan myth is so full of holes you could use it to drain pasta.

The Spartans, popular wisdom tells us, were history’s greatest warriors; in fact, they lost battles frequently and decisively. We are told they dominated Greece; they barely managed to scrape a victory in the Peloponnesian Wars with wagonloads of Persian gold, and then squandered their hegemony in a single year. We hear they murdered weak or deformed children, though one of their most famous kings had a club foot. They preferred death to surrender, as the legend of the Battle of Thermopylae is supposed to show—even though 120 of them surrendered to the Athenians at Sphacteria in 425 B.C.E. They purportedly eschewed decadent wealth and luxury, even though rampant inequality contributed to oliganthropia, the manpower shortage that eventually collapsed Spartan military might. They are assumed to have scorned personal glory and lived only for service to the city-state, despite the fact that famous Spartans commissioned poetry, statues, and even festivals in their own honor and deliberately built cults of personality. They all went through the brutal agōgē regimen of warrior training, starting from age seven—but the kings who led their armies almost never endured this trial. They are remembered for keeping Greece free from foreign influence, but in fact they allied with, and took money from, the very Persians they fought at Thermopylae.

A lot of the blame for our myth-addiction can be laid at the feet of the Spartans themselves, whose mystique is embedded in their relative silence among ancient Greek nations. The Spartans of Laconia left us virtually no writing on how they saw themselves or their world (thus the word laconic). Thucydides describes their defining attribute as secretiveness, and they were famous for their distrust of outsiders. They even purportedly had a policy of not engaging the same enemy in battle repeatedly, out of fear that their foes might learn how they fought.

We are entirely reliant on second- and third-hand accounts of who the Spartans were. The fetishization of the exotic impacts every outsider’s perspective, and contemporaneous writers, from Herodotus to Xenophon to Aristotle, all had a breathless, almost fanboyish fascination with Sparta. A French historian, François Ollier, described this phenomenon as Le Mirage spartiate: “the Spartan Mirage,” the wavering haze of uncertainty that cloaks any attempt to understand a people who above all wanted to be mysterious.

At the heart of the Spartan legend is the Battle of Thermopylae, told and retold in countless books, essays, and films, including the 1962 Rudolph Maté movie The 300 Spartans. One boy who watched the movie, Frank Miller, became a successful comic artist, and he was inspired by the Thermopylae legend to update it in 1998 in the dazzling graphic novel 300. Miller’s comic became a smash hit; it won three Eisner Awards and caught the attention of movie director Zack Snyder, who adapted it in highly stylized form in 2006. The controversial movie offended Iranians with its orientalist portrayal of their Persian ancestors, while Western critics lambasted its fascist iconography. (Not everyone was outraged: National Review ranked 300 as the fifth-best conservative movie of the last 25 years, calling it a “film about martial honor, unflinching courage, and the oft-ignored truth that freedom isn’t free.”)

In the film, Xerxes I, king of kings, leads a Persian imperial army of a thousand nations to conquer Greece. Resistance seems futile, yet 300 Spartan warriors boldly sally forth under a beefy King Leonidas to make a stand at Thermopylae, where a mountain peak and the Malian Gulf forces the advancing Persian horde to funnel into a tight space where their numbers will count for little. The Persians are unable to dislodge the Spartans, who slaughter them like cattle despite the enormous disparity in numbers. So magnificent are these 300 warriors that they surely would have held the pass indefinitely ... if not for the actions of a scurrilous traitor, Ephialtes, a misshapen hunchback who was too deformed to serve in the Spartan line. Enraged at his rejection, he leads the Persians to a hidden path behind his countrymen. Seeing that all is lost, the Spartans refuse to surrender and bravely die fighting to the last man. Their heroic example inspires the rest of Greece to resist, and is directly responsible for the eventual defeat of Persia at the Battle of Plataea the following year.

Both the comic and the film portray this myth with clear racist and anti-immigrant glee. 300 makes no effort to beg off its message—an inspirational paean to brave, muscular, beleaguered white men valiantly barring entry into western Europe from an invading, brown-skinned horde. The filmic Persians are uniformly dark and effeminate. Xerxes is depicted as an androgyne sybarite, his brooding eyes rimmed with kohl, his lips, nose, and ears all pierced with rings linked by delicate golden chains. The seduction of the traitor Ephialtes takes place in Xerxes’s tent, where an orgy is underway that crosses the line from carnal lust into satanic ritual, complete with a cameo by a goat-headed man.

The Spartans, by contrast, are uniformly white Europeans; Leonidas is played by Gerard Butler, who makes no effort to hide his Scottish accent. They appear almost completely nude, fighting in what can be charitably described as booty shorts, their bodies so chiseled it comes as no surprise that the film launched a fitness craze bearing the Spartan name. The year after 300 came out in theaters, equities trader Joe De Sena founded the wildly popular “Spartan Race,” a series of fitness-based, team-building obstacle runs that has been franchised in 30 countries.

300’s plot is at odds with reality. Ephialtes was neither a Spartan nor a hunchback, and may not have existed at all. The 300 Spartans stood at the head of a force of approximately 7,000 other Greeks, not to mention their own helot slaves, who fought as light infantry. And the sum total of this brave last stand wasn’t Greek glory but a paltry three-day delay for Xerxes’s army before he went on to put Athens to the torch. Historian Tom Holland has theorized that the Thermopylae myth was deliberately cultivated by the Athenian general and master spin-doctor Themistocles, in an effort to shore up Greek morale and stave off surrender as the flames of Athens’ occupied Acropolis lit the night sky.

Themistocles perhaps did his job a little too well. We begin to see evidence of Sparta worship gaining currency almost as soon as Leonidas’s severed head was fixed to a stake on Xerxes’s orders.

A bit has been written in these pages recently about the current “tacticool” craze: the lionization of U.S. Navy SEALs and other special operators in imitative street wear that, like laconophilia, speaks to a deep-seated sense of inadequacy. The wildly popular military apparel companies Grunt Style and 5.11 Tactical have huge followings among civilians who have never and will never serve in the military, sporting tactical gear or T-shirts invoking military catchphrases (frequently praising the Spartans), replete with magazine pouches that will never hold ammunition, and FFI (Friend-Foe-Identifier) patches designed to prevent military friendly-fire incidents.

The ancient Athenians had their own “tacticool” phase, it seems. Xenophon reported the famous Athenian philosopher Socrates wearing only a single, filthy, thin cloak, aping Spartan fashion. A bronze from Pompeii depicts Socrates and the philosopher Diotima, showing Socrates in what some scholars identify as the thin cloak of the Spartans—the triboun—and leaning on what could be a bakteurion—the T-shaped staff carried by Spartan leaders and officials. The Athenian orator Demosthenes criticized “men who by day put on sour expressions and pretend to play the Spartan, wearing short cloaks and single-soled shoes, but when they get together and alone leave no kind of wickedness or indecency untried.” Even the famous Aristotle, more critical of Sparta, admitted that its constitution produced virtuous citizens obedient to law. In Aristophanes’s The Birds, the comic playwright notes men “were mad for Sparta; they wore their hair long and honored fasting, they went filthy as Socrates and carried staves.”

The historian Polybius was an Achaean, bound to the Roman alliance that dominated Sparta, which had long been in decline before he wrote in the later Hellenistic Age. Yet even he wrote that if safety and security were what you wanted, “there is not now nor has there ever been government better than Sparta’s.” After its complete fall from power, Sparta remained a tourist attraction for the ancients. The Roman senator Cicero described visiting Sparta to witness the diamastigôsis, the ancient ritual where Spartan boys were flogged bloody, and sometimes to death, before the altar of Artemis Orthia. In the days of Thermopylae, the ritual had been part of Sparta’s famed agōgē, but many scholars believe that in Cicero’s time it was made even more brutal to satisfy the crowds of tourists. In the third century, the Spartans added an amphitheater to better accommodate the crowds who came to watch. Throughout this Roman-dominated period, the purportedly wealth-hating and xenophobic Spartans engaged in the usual methods that tourist economies employ to attract foreigners and separate them from their money: hosting fairs and creating tax-exemptions to attract merchants, encouraging commerce however they could.

Laconophilia marched on throughout Western arts and letters, and always on the same theme—praising the Spartans’ legendary selflessness, restraint, and devotion to duty. The third-century Egyptian Christian apologist Origen Adamantius compared Leonidas’ self-sacrifice at Thermopylae to Christ’s passion. Synesius of Cyrene, a fifth-century Christian bishop, proudly (and falsely) traced his lineage to the Spartan royal houses. In the Renaissance, even Machiavelli got in on the act, praising Sparta in his Discourses on Livy: “That republic, indeed, may be called happy, whose lot has been to have a founder so prudent as to provide for it laws under which it can continue to live securely, without need to amend them; as we find Sparta preserving hers for eight hundred years, without deterioration and without any dangerous disturbance.” (Sparta achieved nothing of the sort, but in Machiavelli’s massaging of anecdotes, the ends justify the means.) John Alymer, the bishop of London just after Machiavelli’s time, called Sparta “the noblest and best city governed that ever was.”

Perhaps the greatest summary of Renaissance attitudes toward Sparta is captured in Michel de Montaigne’s Of Cannibals, which performs the astonishing mental gymnastics necessary to hold the decimation at Thermopylae higher than the successful battles that actually pushed the Persians out of Greece: “There are defeats more triumphant than victories. Never could those four sister victories, the fairest the sun ever beheld, of Salamis, Plataea, Mycale, and Sicily, venture to oppose all their united glories, to the single glory of the defeat of King Leonidas and his men, at the pass of Thermopylae.”

American founding father Samuel Adams lamented that his native Boston would never be the “Christian Sparta” he had hoped for. Fellow founding father John Dickinson considered the Spartans to be “as brave and free a people as ever existed.” Adams’s contemporary, the legendary Jean-Jacques Rousseau, practically drooled over Sparta’s myth, praising “that city as famous for its happy ignorance as for the wisdom of its laws, whose virtues seemed so much greater than those of men that it was a Republic of demi-gods rather than of men.” This just skims the surface, miles wide and fathoms deep, of the legions of historical thinkers and writers in love with the Spartan mirage, distant and wavering.

For much of this time, laconophilia was a relatively benign ahistorical myth, but Spartan admiration unmistakably turned malignant in the late-nineteenth century with the advent of scientific racism. German scholar Karl Müller included in his influential Geschichten hellenischen Stämme und Städte a history of the Dorian race responsible for founding classical Sparta. Müller’s work lionized the invaders’ Northern origins, which dovetailed into the early evolution of Nordicism, the pseudo-anthropological notion of a Nordic master race that would become a cornerstone of Nazi ideology. Müller was hardly alone, and European thinking about inherent inequality and Nordic superiority was already maturing in the fevered minds of thinkers like the French aristocrat Joseph Arthur de Gobineau, whose writings influenced the famous composer and German nationalist icon Richard Wagner. It is not surprising that Adolf Hitler saw in Sparta “the first völkisch state” and gushed about the ancient city-state’s legendary eugenics: “The exposure of the sick, weak, deformed children, in short, their destruction, was more decent and in truth a thousand times more human than the wretched insanity of our day which preserves the most pathological subject.”

Companies like Grunt Style might symbolize today’s molon labe culture, but the phrase has long captured the imagination of would-be warriors holding what they believed were hopeless positions. We cannot be certain that revolutionary Colonel John McIntosh was channeling Leonidas when the British demanded he surrender Fort Morris to them in 1778, but we do know his famous reply: “Come and take it!” The same cry was uttered by Texian settlers 57 years later in response to the Mexican army’s demand that they return a borrowed cannon. The words were emblazoned beneath an image of the cannon on a battle flag flown at the Battle of Gonzales where Mexican dragoons skirmished unsuccessfully with the Texian rebels to decide the matter. As University of Iowa classics professor Sarah E. Bond points out in her own recent critique of Sparta mythmaking, in all these instances, “the phrase stays true to the ancient context within which it was allegedly first spoken.”

That same cannon and phrase are today emblazoned above crossed meat cleavers on the flag of the American Guard—a hard-right white-supremacist group that evolved from the Indiana chapter of Soldiers of Odin USA, an extreme anti-immigrant and anti-refugee group that originated in Finland in 2015. Senator Ted Cruz has repeatedly invoked the same phrase.

Molon labe is the motto of multiple military units, most notably the United States Special Operations Command Central. But the phrase has special currency with the National Rifle Association and the gun-advocacy community in the United States, where it is a warning growl of the willingness to use violence to uphold the right to bear arms against government infringement. A quick search on social media will reveal the words in both English and Greek—almost always blazoned beneath the stylized Corinthian helmet—inlaid into gun handles, tattooed on skin, and pressed on T-shirts, key chains, pens, bumper stickers, and patch after patch after patch, usually velcroed onto tactical packs carried by military and civilian alike. Molon labe is so synonymous with right-wing gun-fetishism that political opponents have coined a mocking term, “moron label,” to counter those under its thrall.

But this twisted veneration of the Spartan myth looms larger than just Leonidas’s single quote. Thermopylae imagery was rife among supporters of Trump’s presidential bid. A still-public 2016 YouTube video posted by a user under the handle “Aryan Wisdom” depicted then-candidate Trump as Leonidas, holding back a Persian army that included Soros and Obama. At the time of this writing, the video has been viewed over five million times. The far-right white nationalist Identitarian movement’s symbol, blazoned in gold against a black background, is the circle of an aspis, the round shield that was a Spartan warrior’s principal piece of equipment. It is divided by the upside-down V of the Greek lambda, the sigil falsely believed to have been painted on Spartan shields at Thermopylae. “Generation Identity,” a fast-growing European Identitarian party, explains the significance of adopting the Spartan shield for its movement by way of relating the 300 myth: “Both ancient and modern writers have used the Battle of Thermopylae as an example of the power of a patriotic army defending its native soil.” This appears on the site’s “frequently asked questions” page, just above a section titled “What does the term ‘Great Replacement’ mean and who is responsible for it?”

The myth of Sparta that was born at Thermopylae has endured for millennia, hardier than a tardigrade, preying on the pervasive insecurity that we are too decadent and too comfortable, not tough or disciplined enough, and that a return to mythic and long-lost standards of militant self-denial and monocultural purity will somehow restore us to greatness. In 2019, it has become a frightening symbol in a cultural war that’s increasingly marked by murder, terror, and sanctioned discrimination.

There’s a famous maxim—frequently misattributed to Orwell, sometimes to Churchill—that people sleep peaceably in their beds at night only because rough men stand ready to do violence on their behalf. Frank Miller, the comic artist who created 300, has offered a variation of this line in defense of the Spartan myth. “They were utter fascists,” he conceded, but suggested that a little fascism at the margins had its use: “The Athenians were the ones who gave birth to democracy, but the Spartans made it all possible.” However uncomfortable the idea of an ancient proto-fascist state may make us, this reasoning goes, we need the rough men of a Sparta to protect the fragile democracy of an Athens.

This tacit acceptance of might-makes-right rings doubly hollow in light of last week’s recall of a Navy SEAL platoon from Iraq due to rampant misconduct, including allegations of rape. It’s just the latest in a litany of recent alleged crimes and ethical lapses in the U.S. community of elite, tip-of-the-spear warfighters, whose unassailable mythos in America’s Long War seems to have trumped careful oversight and accountability. Super warriors are as fallible as anyone else, it turns out, and strength is not the same as sound judgment or moral rectitude.

Still, the Spartan myth is a powerful catalyst, both for racist vanguards and the political machines that cater to them. Laconophilia alone cannot fully explain the Trumpist vision of a sealed, homogenized, and militarized America, but it explains a lot. Steve Bannon—the alt-right pioneer so instrumental to the rise of Trump as an avatar for nativist hopes—loves classical war literature and is an avid fan of Thucydides’s history. I couldn’t find him personally lavishing any love on Leonidas or “the 300” in on-the-record interviews or writings, but the influence was there in the computer password he shared with co-workers at his California office, before moving into the White House to advise a president taking the first tentative steps to undermine cherished American values of plurality, liberalism, and justice. The password, his colleagues said, was “Sparta.”