It may be hard to believe now, but Lindsey Graham was once considered a relative moderate. During the Obama years, the South Carolina senator backed legislation that would create a legal path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, worked with Democrats on proposals to tackle climate change, and voted to confirm Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan to the Supreme Court. The Obama White House offered some praise for Graham’s friendly approach in 2010 while conservatives lambasted him as “Obama Lite” and “Lindsey Grahamnesty.”

That version of Graham wasn’t apparent when he appeared on Fox News last week. President Donald Trump was facing intense backlash for calling on four young nonwhite Democratic congresswomen to “go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came.” While some Republicans tried to distance themselves from those remarks, Graham did the opposite. “We all know that AOC and this crowd are a bunch of communists,” he complained. “They hate Israel. They hate our own country. They’re calling the guards along our border—Border Patrol agents—concentration camp guards. They accuse people who support Israel of doing it for the Benjamins. They’re anti-Semitic. They’re anti-America.”

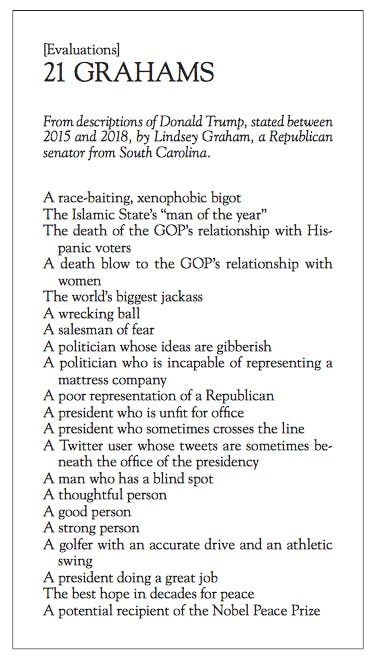

What happened to Lindsey Graham? Many journalists have spent the last two years trying to answer the question. New York magazine’s Lisa Miller cast him as a people-pleaser who’s long tried to build ties with both his party’s right flank and centrist Democrats. CNN placed him alongside other moderate GOP senators who’ve bowed to the president’s grip on the party base. The New York Times’ Mark Leibovich hinted that it was pure self-interest. Perhaps the most succinct analysis came from Harper’s, which simply listed 21 ways Graham had described Trump over the past three years. It begins with “a race-baiting, xenophobic bigot” and ends with “a potential recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.”

The fascination with Graham’s transformation is justified. More than any other figure in conservative politics, he represents the Republican Party’s capitulation to Trumpism. He isn’t patient zero for this infection in the American body politic, of course. But the symptoms of fealty are so much more pronounced in Graham that they demand interrogation. By studying how the illness spread to him and reached its current stages, those trying to grapple with Trumpism hope to learn how it will run its course. Ultimately, though, the diagnosis may be less illuminating: Graham was never the principled Republican the press made him out to be.

Among those who have most shamelessly sold out to Trumpism, Graham’s closest competitors are former Texas Governor Rick Perry, who once denounced the president as a “cancer on conservatism” and now serves as his secretary of energy. Texas Senator Ted Cruz upended the 2016 GOP convention by pointedly refusing to endorse then-candidate Trump in a prime-time speech, then reversed course two months later after Trump added a few more names to his Supreme Court shortlist. In 2016, Mick Mulvaney, then a congressman and founding member of the Freedom Caucus, said, “Yes, I am supporting Donald Trump, but I’m doing so despite the fact that I think he’s a terrible human being.” He’s now the acting White House chief of staff.

But Graham stands apart. He’s more obsequious than most other top Republicans, often willing to appear on Fox News to defend Trump when others won’t. Even Mitch McConnell, one of Trump’s most reliable allies in the Senate, largely treats his relationship with the president as transactional. With Graham, however, the relationship appears to run deeper. The senator and the president regularly speak by phone and bond over their mutual love of golfing. After one such excursion in December 2017, Graham promoted Trump’s golf course on his personal Twitter account.

This wouldn’t be so remarkable if the president were, say, Jeb Bush. (In fact, Obama received his fair share of criticism for not building closer relationships with Democratic lawmakers on Capitol Hill.) But the buddy routine is a dizzying reversal from Graham’s past views. In the summer of 2015, he referred to Trump as the “world’s biggest jackass,” prompting Trump to retaliate by publicly revealing Graham’s personal cell phone number. “You know how to make America great again?” he quipped in a CNN interview that fall. “Tell Donald Trump to go to hell.” In a Twitter post from 2016 that goes viral anew whenever Graham publicly defends the president, he wrote, “If we nominate Trump, we will get destroyed.......and we will deserve it.” The list goes on.

So why the embrace? Political necessity partially explains it, as Graham nears reelection in 2020. Trump’s grip on the Republican primary electorate means candidates often need his support—or at least his silent assent—to win. There’s also some historical incentive for Graham to stay on his good side. As I noted earlier, the senator, who rose from the House to the upper chamber in 2003, was one of the few Republicans who regularly tangled with the insurgent Tea Party. But the timing of his reelection was fortunate: The anti-incumbency wave that swept through the GOP ranks in 2010 and 2012 had largely crested by 2014. The MAGA mood within the party, by comparison, is alive and well.

Access to power is the other part of the equation. Graham has made clear how much he craves the influence that his supine praise brings. “I have never been called this much by a president in my life,” he told the Times’ Leibovich in February. “It’s weird, and it’s flattering, and it creates some opportunity. It also creates some pressure.” Leibovich wrote that Graham spoke with “a mixture of amazement and amusement, with perhaps a dash of awe.”

It’s hardly novel for people to appeal to Trump’s vanity to get things out of him. That’s part of Graham’s strategy as well, especially on foreign policy matters. Though Trump is no peacenik, his skepticism toward prolonged U.S.-led interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq set him apart from the rest of the Republican field in 2016, especially compared to an uber-hawk like Graham. The flattery seems to have worked: Trump described Graham in February as someone “I respect, I listen to” on the Middle East. But Graham’s efforts to ingratiate himself go beyond mere policy issues, as he suggested to Leibovich.

“Well, O.K., from my point of view, if you know anything about me, it’d be odd not to do this,” he said.

I asked what “this” was. “ ‘This,’ ” Graham said, “is to try to be relevant.” Politics, he explained, was the art of what works and what brings desired outcomes. “I’ve got an opportunity up here working with the president to get some really good outcomes for the country,” he told me.

No matter how justified Graham thinks those causes may be, his defenses of Trump still lead to dark places. Graham, who once warned that firing Special Counsel Robert Mueller would be the “beginning of the end” of Trump’s presidency, morphed into a fierce critic of the Russia investigation and the “deep state” supposedly behind it. When a reporter asked last week whether he thought the president’s attacks on Congresswoman Ilhan Omar were racist, Graham gave a novel explanation for why they weren’t. “A Somali refugee embracing Trump would not have been asked to go back,” he replied. “If you’re a racist, you want everybody from Somalia to go back cause they’re black or they’re Muslim.”

If Graham thought this was a defense of the president, he’s wrong. White supremacists have often set aside their hatred of nonwhite political figures for strategic reasons, as when Ku Klux Klan leaders met with Marcus Garvey or George Lincoln Rockwell addressed the Nation of Islam. Likewise, Trump is friendly toward individual people of color when they are his political allies and his public supporters (see: Kanye West). Graham’s interpretation of the president’s views here—that nonwhite Americans’ citizenship is contingent on their allegiance to the sitting president—is accurate. That he doesn’t seem to consider this morally abhorrent is the problem.

The most favorable interpretation of Graham’s actions is that he’s not spellbound by Trump in particular, but rather just willing to bow to whoever’s in charge in Washington. It’s the thread that connects his close ties to the George W. Bush administration, his across-the-aisle outreach to the Obama White House, and his awkward zeal to ingratiate himself with Trump. Plenty of politicians gravitate toward power and leap at any fleeting chance to exercise it; Graham just does it particularly well.

The tragedy of Graham’s reversal is that his initial assessment of Trump was correct. The president acts just as despicably as the South Carolina senator warned he would. Trump’s hostility toward the rule of law and his embrace of white nationalism are a defining challenge for this country. How Americans respond to this presidency is their ultimate moral test. Lindsey Graham may yet try to reinvent himself as a reasonable moderate partner for the next president. But for those who became sycophants to a racist golfer for personal gain, there can be no going back.