The notion of “privacy” has done a lot to protect predators. The #MeToo movement has tried to trespass on that boundary, to remove the veil that had hidden the behavior of successful men. But ordinary people are not subject to the same scrutiny as the famous, so it remains very difficult to know what is really going on in the seclusion of American homes. Have things actually gotten any better for women in intimate partnerships with men, or no?

Decades of seeming empowerment, after all, gave way to the Trump era; the #MeToo movement, for all its groundbreaking accomplishments, has coincided with lawmakers, not to mention millions of voters, turning a blind eye to credible accusations of rape against the president. That must have a ripple effect on American lives. As Dayna Tortorici of n+1 observed in an essay last year, millennial women grew up being told that “you can do anything”—but the pervasive misogyny in this country has made us feel naïve, as if we were taught lessons as little girls that are already hopelessly out of date.

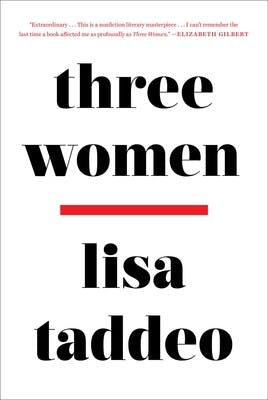

The ambivalent politics of heterosexual intimacy arch over Lisa Taddeo’s Three Women, an investigation of the sexual desires of three women. In her prologue, Taddeo explains that she has been lately haunted by memories of her own mother’s extreme passivity when it came to sex: “Sometimes it seemed that she didn’t have any desires of her own,” Taddeo writes. “That her sexuality was merely a trail in the woods, the unmarked kind that is made by boots trampling tall grass. And the boots belonged to my father.” These troubling thoughts sent Taddeo on a years-long mission to report on how women today conceive of and narrate their own needs. She started interviewing women, hundreds of them, before focusing on three: Lina, Maggie, and Sloane, all straight, all white.

For a young feminist, Three Women is a deeply discouraging book that suggests that much less has changed about men and women’s romantic relationships than we (or at least I) had assumed. That’s because each of Taddeo’s women suffers, horribly, through a combination of internalized misogyny that stunts their maturity and mistreatment at the hands of cruel or stupid men. They speak to themselves in the voices of their own abusers.

Reading Three Women is at times a slog, like doing homework for a necessary but terrifying exam. But if we look away from the reality of these private lives, Three Women argues, then the sexism that inheres in so many romantic relationships will remain static. If you really care about women, Taddeo challenges her reader, stay and listen to their stories.

We meet 23-year-old Maggie on the first day of her court testimony against a former high school English teacher who groomed her for a sexual relationship. To the teacher’s lawyer, Maggie is a slut with an overactive imagination, desperate to cling to anybody who showed interest. But we know different: “Look at me,” she thinks to herself, looking at the teacher: “I put this war paint on, but underneath I’m scarred and scared and horny and tired and love you.” The teacher’s charm has gone but her obsession remains. “He looks sickly, as if he’s been eating muffins and drinking AA coffee and Coca-Cola and sitting in a drafty basement scowling at the wall.”

Maggie struggles to maintain her identity while other forces—the courts, nasty gossips—send distorted versions of herself into the wider world. Lina is in a similar position: On the surface, she is humiliating herself every time she sneaks out of her conjugal home (her husband won’t touch her) to fuck an old boyfriend in the backseat of his car. But that soap-operatic setup doesn’t explain the intensity of her desire, which throws all other concerns out of the window. Slowly, Taddeo unfolds the story of Lina’s youth, explaining how a history of sexual violation might one day cause an obedient young woman to wake up convinced that she will die if somebody doesn’t touch her soon.

Lina and Maggie’s stories are maddeningly familiar, not just because the men in their lives are so cruel, but also because both women’s sexualities are founded on traumatic experiences from their youth. This is one of the toughest betrayals to confront, for a politically conscious woman who dates men: the realization that your desire for men, which you can do little to alter, is inextricably woven with every other interaction you have had with men, including the bad. Predatory attention in childhood; sexual assault; the ego-crushing disdain of a sexist teacher—it’s all part of the matrix.

If Lina and Maggie’s stories demonstrate the monstrous power of male attention to pull a woman’s mind apart, Sloane’s teaches something different. She seemingly has everything: a restaurant she owns, lots of money, a lovely husband and kids, a great body and pretty hair. She is a success in the gendered economy that gives material rewards to desirable women. Then her husband asks if she will have sex with other men and women in front of him. She obliges, but is unsure why. Does she wish to see herself reflected in more people’s eyes, since her beauty is the core of her sense of self? Or has she molded her sexuality to fit her husband’s voyeurism?

Three Women has been billed as a woman’s response to radical investigative nonfiction like Gay Talese’s Thy Neighbor’s Wife, but it echoes two other literary genres. The first is fiction about women’s abjection, like Chris Kraus’s novel I Love Dick, a tract of letters about the protagonist’s humiliatingly unrequited crush. It issues the same challenge as Three Women: Can you, feminist reader, really know my secret desires without judging them?

I struggled with feelings of disdain at Lina’s behavior, at Sloane’s egotism. But that says as much about me—about my own experiences, my own relationship to male attention—as it does them. If it makes me angry to learn that America is still full of women who walk around judging themselves according to the standards of an internalized male voice, then that’s my problem for being ignorant. Taddeo never explains the significance of the data she has so painstakingly collected; she just writes it down. What the reader does with it—what the reader sees in herself—is the reader’s business.

The second genre is the Victorian romance novel. Maggie is obsessed with Twilight, spending nights fantasizing about an ageless vampire lover. Sloane loves Fifty Shades of Grey, its schmaltzy BDSM scenes inspiring her to act them out. But those novels are just intermediaries: Twilight contains many references to Emily Brontë’s tale of abusive love, Wuthering Heights, while Fifty Shades uses Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles as a motif. In Fifty Shades, the heroine Anastasia sees herself as Tess, the victim, while her dominant lover says that he wants to “debase [her] completely like Alec d’Urberville.” Sloane longs for the same kind of debasement, a submissive sexual identity that will make her as innocent as a young country girl (and conveniently satisfy her husband’s own desires). Maggie’s fantasies about vampires sucking her blood are as morbid as Brontë’s story of a dead girl named Cathy.

Twilight and Fifty Shades are stigmatized “chick lit” novels, but both draw on deep storytelling tropes about what women want and how badly the world likes to punish them for it. It is natural that Taddeo’s women relate to this seam of romance literature, because it is designed to make the agonies and ecstasies of women’s desire seem heroic.

If Three Women is supposed to challenge the reader to respect its subjects’ desires, even when they seem retrograde or degrading, then the reader must acknowledge these three women’s inalienable right to act like tragic heroines. But if female sexuality is in fact a fluid and endlessly revised substance that feeds off literature as much as lived experience—as Sloane and Maggie seem to suggest in their reading habits—then women’s sexuality is a learned phenomenon that can change, can be critiqued. It would mean moving toward a politics not of radical acceptance but instead radical disclosure, a communal moment of reckoning with the voices in our own heads, made audible to others at last.

Three Women doesn’t come down firmly on one side or the other. At its best, the book reflects the reader back to herself, and asks a simple question: Are you just as biased as a garden-variety sexist when women act in ways you disapprove of? America may be finally learning to speak the language of feminism, but this book demonstrates that the broad strokes of #MeToo and #BelieveWomen are not detailed enough to convey the difficulty of heterosexual desire—and the pain of knowing that your desires have been shaped by trauma. Audre Lorde once said that she was not free while any woman was unfree, even when her shackles were very different from Lorde’s own. To receive the lessons of Three Women and accept them, in oneself and in others, provides an opportunity for personal and collective forgiveness. Only more freedom will follow.