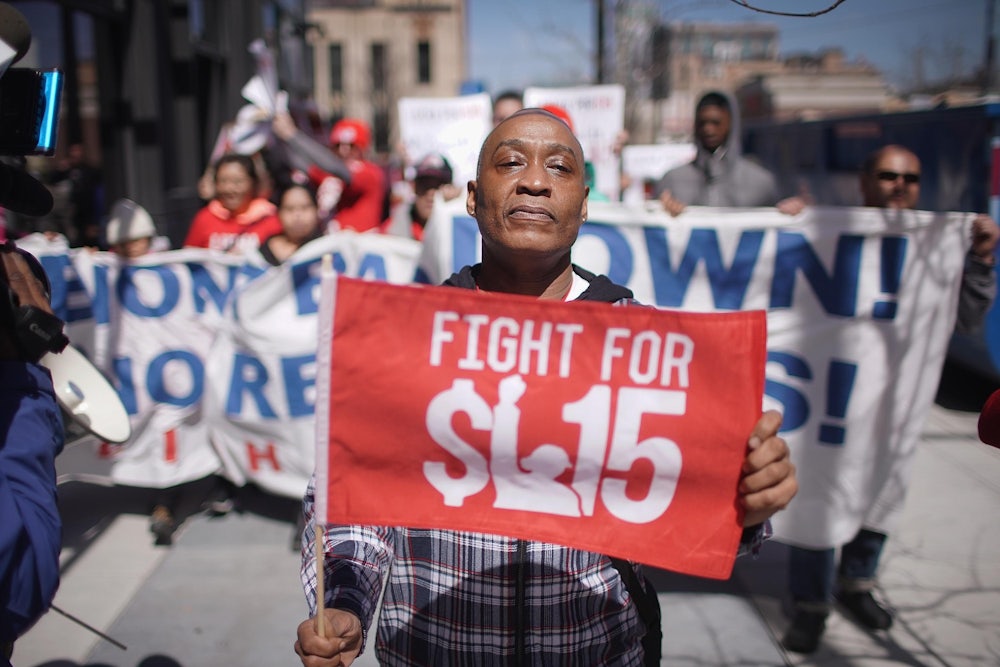

The Democratic Party has moved left on myriad issues in recent years, but perhaps nowhere more dramatically than on the minimum wage. It wasn’t long ago that President Barack Obama and Democrats in Congress were agitating for $10.10, while the demands of the Fight for $15 movement were seen as extreme. In 2016, when Bernie Sanders ran on a $15 wage floor, Hillary Clinton would only agree to $12.

But on Thursday, the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives is likely to pass legislation that would raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour. The vote is mostly symbolic, given Republican control of the Senate and White House. But the expected passage of the Raise the Wage Act is already stirring a familiar debate: Will raising the minimum wage “kill jobs,” or will it be a boon to the people who earn the least?

It’s not an either/or question. There’s not likely to be much job loss, if any at all. But even if a higher minimum wage killed a few million jobs, would it still be worth it? In a country that has churned out jobs but left millions in financial insecurity, the answer is yes.

A huge body of research shows that minimum wage increases aren’t massive job killers. One study that looked at 138 increases between 1979 and 2016 found that they basically had no net impact on low-wage jobs. Another that examined increases in 1,381 counties over 16 years found no effect on employment. Yet another that looked at a quarter century of state-level hikes found the same, even when unemployment was already high. A more recent paper studying 138 state-level minimum wage changes between 1979 and 2016 found that the number of low-wage jobs was basically unchanged for five years after an increase, even after large ones. A survey of 61 studies found that when the impact on jobs was averaged out, the impact was close to zero jobs lost, and the most statistically precise were the most likely to find no impact.

But there is still the remaining question as to what would happen if we were to essentially double the minimum wage, moving from the current $7.25 an hour to $15 an hour. We don’t know for sure, of course, because Congress has now left the minimum wage stagnant for the longest period in history. But a recent paper looking at similarly large local increases tried to answer that question and found that even such big percentage jumps didn’t hurt employment or even the number of hours people worked.

If there is an employment reduction, it’s also unlikely to mean that a whole bunch of people are fired en masse. More likely it will reduce hours for some workers but not toss them out of jobs completely. It’s possible that at least some of them will still come out ahead because an increase in their hourly pay will more than make up for the decrease in their hours. The question isn’t so much whether the minimum wage will destroy a huge swath of businesses and therefore jobs, but possibly reduce work for some low-wage workers.

Nonetheless, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated recently that a national $15 minimum wage would cost jobs. It noted that there is a lot of uncertainty about its analysis; there is a two-thirds chance that the change in employment would fall somewhere between nothing and a loss of 3.7 million jobs—two hugely different scenarios. Still, its median estimate is that 1.3 million people would lose their jobs.

Even if we take that claim at face value, it’s worth examining whether the trade-offs would be worth it. While the CBO estimated that 1.3 million people might become unemployed, the same exact net number of people would be lifted out of poverty, making $600 more a year on average. That’s a significant increase for a family of four living off of less than $26,000 a year. On the whole, if the country’s minimum wage were raised $15 an hour, 17 million people would get a direct raise; another 10.3 million people would likely earn more as employers raised wages slightly above the minimum to keep them in the same relative standing. That means that over 95 percent of the workers impacted by a $15 minimum wage would get a pay increase, on average seeing annual earnings go up by more than $1,500.

The phrase “working poor” has become too familiar in this country. There are millions of people who work but still don’t earn enough to make ends meet. A full-time minimum wage job isn’t enough to afford a one-bedroom apartment almost anywhere in the country. Even in our robust economy, a quarter of American adults say they are either just getting by or struggling to do so; 14 percent of those who work as many hours as they want still say they struggle financially. About 40 percent would have difficulty covering an unexpected $400 expense. This is true despite the fact that job creation has been on its longest streak in history and corporate profits have climbed to record highs. What’s the point of a thriving economy if so many people are left in financial deprivation and economic insecurity?

The minimum wage is partly to blame for the persistence of financial instability. The government is supposed to ensure that businesses pay their workforces a bare minimum, but Congress has shirked that duty for twelve years. Without a higher wage floor, companies can legally get away with underpaying employees to the point that full-time workers struggle to afford food and rent.

If a business can’t afford a wage increase that would allow its workers to make ends meet, then maybe that business shouldn’t exist. There’s evidence that an increase in the minimum wage would most impact these kinds of businesses—ones that are just barely hanging on anyway. A recent paper found that the restaurants that are driven out of business after cities raise their minimum wages are the ones with the lowest customer ratings. The hardship of those businesses’ employees as they face joblessness shouldn’t be glossed over. But as higher wages across the economy put more money in consumers’ pockets, prompting them to spend more and generate more economic activity, those unemployed workers may be able to look forward to more lucrative employment at a company that manages to come up with a business model that both makes money and adequately rewards its workforce.

In order to get centrist Democrats on board with the Raise the Wage Act, its supporters agreed to add an amendment to study the economic impact of the first two planned hikes—one to $8.55 and the next to $9.85. It makes all the sense in the world to try to measure the impact of an increase in the federal minimum wage. But that picture isn’t complete without looking not just at the change in jobs, but at changes in the lives of those at the bottom of the income scale: whether millions have been lifted out of dire poverty, and whether more workers were able to provide for themselves and their families. After all, that’s the whole point of a minimum wage: to ensure that every American can live on a full day’s labor.