The 2019 hurricane season has barely begun, and a troubling storm is already brewing. Heavy rains paralyzed New Orleans on Wednesday, with as much as ten inches falling in just a few hours, and the National Weather Service declared a “flash flood emergency.” This is just the beginning of what could be a truly awful week of weather.

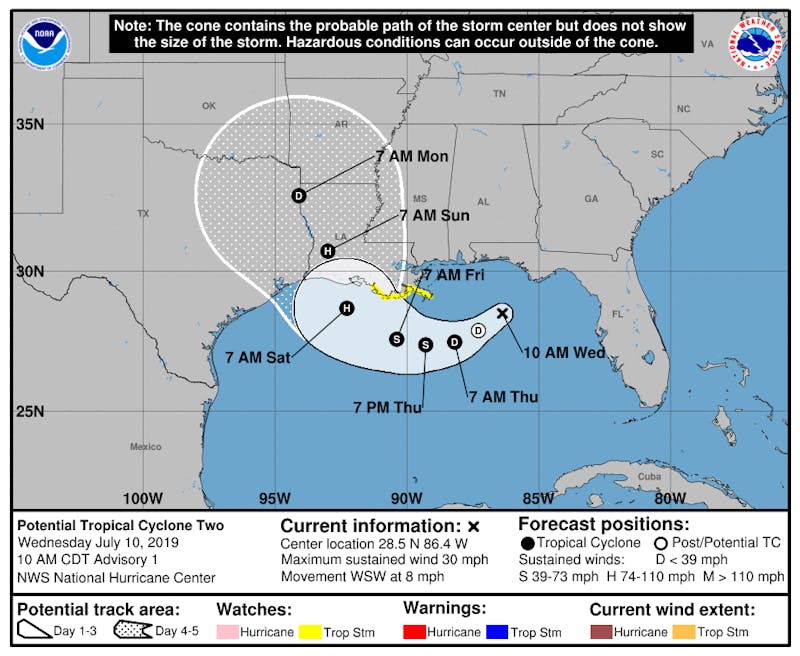

On Wednesday morning, the National Hurricane Center issued a storm surge watch and a tropical storm watch for coastal Louisiana, forecasting the ongoing thunderstorms to eventually develop into a hurricane which would be named Barry and make landfall sometime on Saturday. The National Weather Service (NWS) office in New Orleans has begun circulating hurricane preparedness tips, and the NWS’ Twitter account said—in a since-deleted tweet—that the approaching storm “gets us thinking about what we can be doing TODAY to get ready for the big one.”

The storm’s timing is unique: In 168 years of hurricane records, a July hurricane in Louisiana has only happened three times, and all of those occurrences have been within the past 40 years. There’s a growing body of research that shows that as the Gulf of Mexico waters warm because of climate change, early-season hurricanes like proto-Barry could become more common. (Right now, water temperatures in the Gulf are at near-record levels, more typical of peak hurricane season.)

More concerning than the storm’s early timing, however, is its bad timing. The Mississippi River has been continuously flooding southern Louisiana since January 6, the longest flood in recorded history for the river in this region. Spring floods aren’t supposed to last until mid-July, and after 185 days of high water, it’s unclear Louisiana could handle any more. A potential worst-case scenario could prove disastrous for Louisiana, and shows how unprepared we are for the scary new era of overlapping climate disasters.

In Louisiana, there are two types of levees: those that protect the coast from an ocean storm surge, and those that are designed to keep the Mississippi River in its current course. Katrina caused a failure of the storm surge levees. This week, the river levees—which were first built after the historic 1927 flood—are being put to the test for the first time in modern history.

As much as 15 to 20 inches of additional rain is possible this weekend as the storm moves inland, according to the latest weather models. And because Barry’s storm surge could essentially block the flow of the river from reaching the Gulf of Mexico, the National Weather Service now forecasts that the Mississippi may rise to 20 feet—the highest crest since 1927, before the modern levee and spillway protection system was completed. In New Orleans, the river levees are only 20 feet high in some places.

Bourbon Street is flooded #NewOrleans https://t.co/enXI6uwyn4 pic.twitter.com/1YHQAcEfqA

— Greg Diamond (@gdimeweather) July 10, 2019

In recent years, extreme river floods have begun happening with increasing frequency as the spring rains arrive earlier each year as the atmosphere warms. In 2011, a flood came dangerously close to breaking the levee system upstream from New Orleans. At that time, officials feared that in a worst-case scenario, parts of the levee system could “slide into the river” if the earthen barriers became too saturated with floodwaters.

A river levee breach would be an entirely different type of flooding disaster than what occurred during Hurricane Katrina, but possibly no less devastating. Depending on where exactly a breach occurred, it may not be possible to return the Mississippi River to its previous state. This would cripple America’s agricultural and petrochemical industries, deal a potentially fatal blow to New Orleans, and change the course of American history.

Of course, it’s possible none of this will happen. But the odds are growing that, if not this week, it will happen someday soon. Even if Barry steers away from Louisiana, this won’t be the last time the region has to deal with the dual threat of extreme late-season flooding and extreme early-season hurricanes. As the climate continues to warm, the atmosphere will continue to be able to hold more moisture, increasing the likelihood of intense rainfall in already-wet areas.

The region is not prepared for this increasing threat. More than a decade after Katrina, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has only just finished the reconstruction of the storm surge levees after Katrina in the past year. That reconstruction came at a cost of $14 billion—and already, the Corps has noticed problems with the system, which is settling at a faster rate than expected when it was designed in 2007 and may no longer be able to provide adequate protection from the rising seas.

Overlapping extreme-weather events aren’t just a New Orleans problem. In November, a team of researchers found that unless carbon emissions are greatly reduced, by the end of the century many parts of the world would face overlapping disasters most of the time. Drought will worsen the water scarcity caused by the over-pumping of aquifers. Rising sea levels will make the storm surge from hurricanes even more destructive. The combination of extreme heat and wildfire smoke will create widespread public health crises. These disaster overlaps, they said, would magnify the intensity of the climate crisis and “pose a broad threat to humanity.”

Already in 2019, we’ve seen overlapping disasters in Mozambique, which in the span of a month endured two of the worst cyclones ever to hit the Southern Hemisphere, and in India, where Chennai, a city of seven million people, ran out of water after the delayed start of a second consecutive monsoon season. If New Orleans’ levees hold this week, it will be because we were lucky. But the more carbon dioxide we pump into the atmosphere, the sooner our luck will run out.