The moon belongs as much to art as to science. In the eighth century, the Venerable Bede described an eclipse correctly in flourishing prose, and vibrant illustrations of the satellite’s phases abound in medieval manuscripts. Once we could really see the thing up close using telescopes, studies of the moon came to a fork in the road—between fantasy (like George Méliès’s 1902 movie Le Voyage Dans la Lune) and scientific inquiry (like Charles Le Morvan’s exquisite portfolio of photogravure prints, the 1909 Carte photographique et systématique de la lune). But the two approaches remained, and remain, linked. An astronomical textbook is totally different from a novel by H.G. Wells, but both are about the same moon.

It is fitting, therefore, that this most hybrid of celestial bodies has had such an intimate relationship with photography, which is itself a medium jointly claimed by art and science. A new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—Apollo’s Muse: The Moon in the Age of Photography—pinpoints this nexus in cultural history. The show is named after Apollo 11, the spacecraft that put two men on the moon half a century ago this year. Abe Silverstein, a NASA manager, named the project one evening at his home in Cleveland in 1960: “Apollo riding his chariot across the Sun was appropriate to the grand scale of the proposed program,” he wrote.

It remains astonishing to contemplate the fact of the moon landing. (As The Onion headlined the event in the book Our Dumb Century, “Holy Shit Man Walks on Fucking Moon.”) How can we get purchase on an event that sliced across the whole of reality, before it slips out of the reach of living memory? A slew of books has been released this year to commemorate Apollo 11’s fiftieth anniversary, but this esoteric show at the Met, in its refusal to separate art from science, offers a powerfully expressive answer to that question.

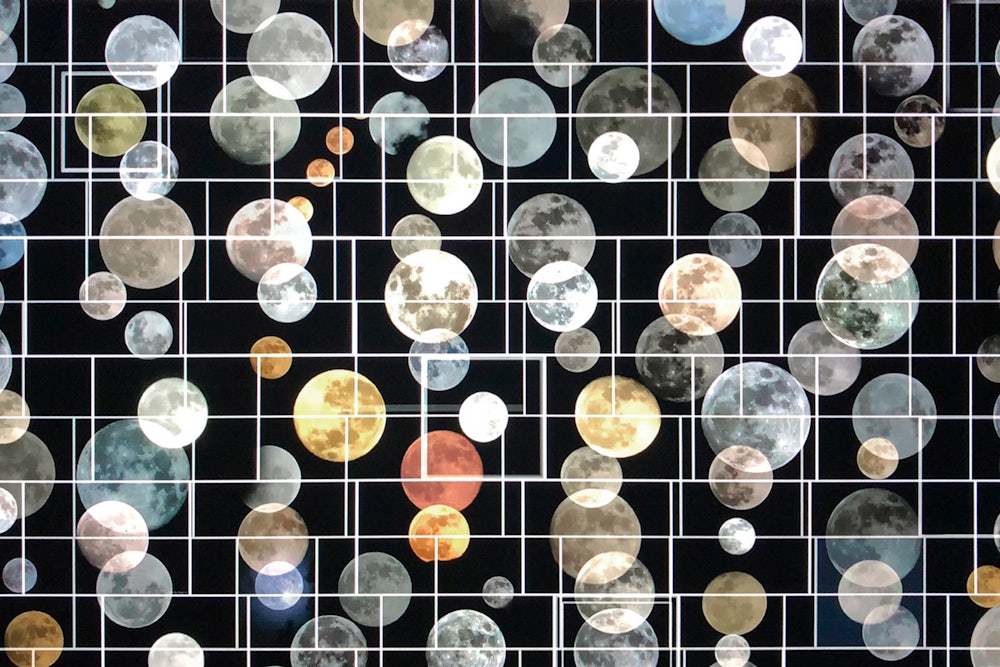

Apollo’s Muse benefits from its lovely heroine. It is unusual to see an exhibition full of images—from the early days of photography to postmodern reinterpretations of that photography—of the exact same object, rather than images grouped by genre, period, or artist.

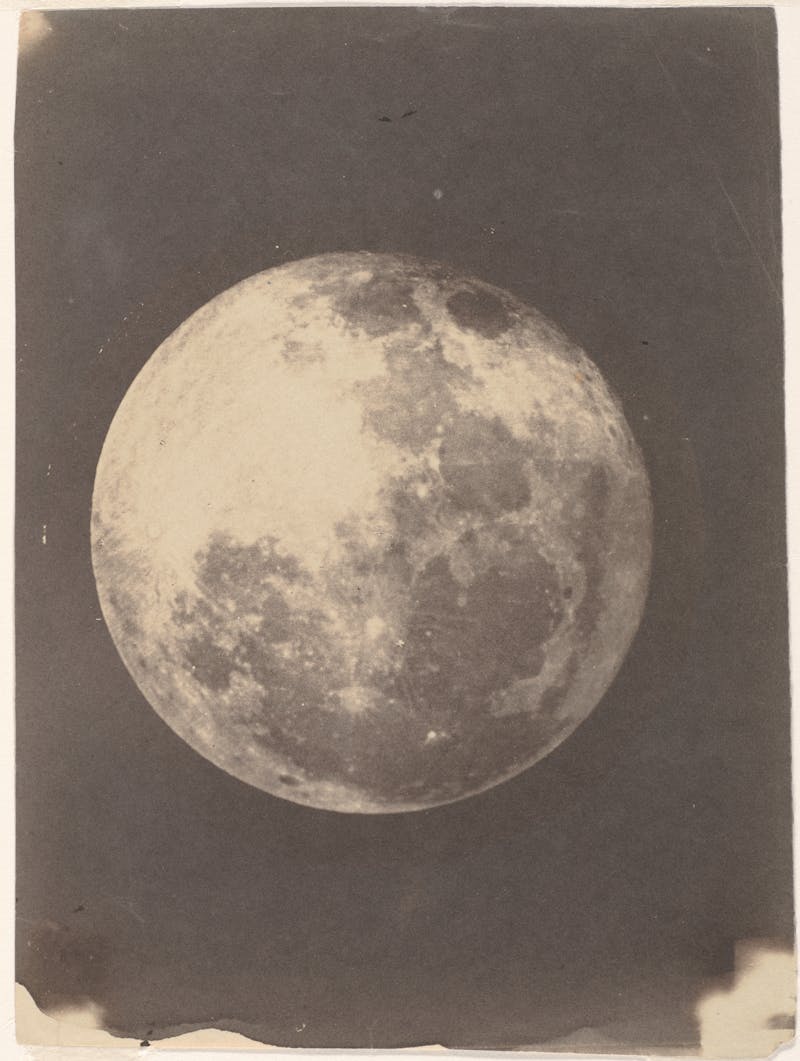

The show moves chronologically. We begin in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when European artists engraved maps of the moon (the first was in 1645) as contributions to “selenography,” the study of its surface. The first daguerreotypes of the moon, by John William Draper in the 1840s, are so close-up that you can see the craters. Indeed, the very concept of photography was bound up with the moon from the beginning: When François Arago announced the invention of photography to the French Chamber of Deputies in 1839, he lobbied for grant money for Daguerre so that he could pursue important projects like photographing the entire visible surface of the moon. The images rippled through society, blowing minds, especially after the “moon hoax” of the 1830s suggested there might be small deer up there.

At the same time that scientific photography was advancing, the nineteenth century’s Romantic yearnings made the moon into an object of supernatural longing. That spirit is best heard in music from the period, like Dvořák’s “Song to the Moon,” the aria from Rusalka sung by a mermaid in search of a love. But Romanticism made its way into moon-ish photography too, as in the photographs of the Italian Carlo Naya, who shot cheesecake images of Venice’s Grand Canal by “moonlight,” which was actually daylight manipulated in the darkroom.

A substantial chunk of Apollo’s Muse is devoted to the picture postcard rage of the early twentieth century. Tourists flocked to new fairground attractions like the “Trip to the Moon” ride at New York’s Luna Park (named for the ride), and made mementoes. Children, groups of friends, couples, and elderly people perch on the moon’s hook, beaming into the camera, acting out a carnivalesque prefiguration of the events of 1969.

Three early

moon-movies play in sequence on a monitor: Méliès’s Le Voyage Dans la Lune,

Fritz Lang’s Frau im Mond (1929), and Irving Pichel’s Destination Moon

(1950). The first is intentionally hilarious: A gang of tail-coated and

top-hatted astronauts jump out of a tin can on the moon, framed by a theatrical

proscenium. They venture underground into a chamber that contains huge fungi

and a green alien who disappears in a puff of smoke when hit with an umbrella,

only to regenerate instantly. Lang’s movie is scientific in feel, including

diagrams of the moon’s trajectories. His rendition of a moon landing is less

compelling than the scenes of people watching the moon landing: He films

a group around a table in chiaroscuro, including a woman smoking a cigar,

anticipating the enormous numbers of people who would later watch the actual moon landing in 1969. Pichel’s movie is strongly reminiscent of

early Star Trek; it shows an astronaut taking “possession of this

planet” as an extraterrestrial territory of the United States. Cinema, it turns

out, had cast the moon landing as a high water-mark for American ambition long

before it became realistic to achieve it.

The room of NASA exhibits is shockingly beautiful, because all of the photography on the early expeditions was done on film. Apollo astronauts brought special 70-millimeter cameras with Zeiss lenses and super-thin Kodak film, which was later processed in Rochester, New York, the site of Kodak’s headquarters. The tiny prints had to be put together into scale-like mosaics in order to create a full panorama.

The big hitters are harder to comprehend. The moon landing video itself is unimpressive when you see it played on a loop across on a vintage monitor in a museum: grainy, short, confusingly mixed with CBS animations. The iconic photographs, 1968’s Earthrise and 1972’s Blue Marble (reportedly the most widely reproduced photograph ever taken), are too familiar to prompt any kind of feeling at all.

The exhibition closes with a flourish of contemporary art—a very wise decision on the part of the curators. We need art to process the moon for us, just as much as we need the moon to act as a repository for our fears and desires. A work by Darren Almond hangs in large format, sun-kissed leaves recalling long summer afternoons spent in love; in contrast to Naya’s Venice, it turns out to have been shot by the actual light of the full moon, with a 15-minute exposure. An image from Cristina de Middel’s The Afronauts refers to a real Zambian man named Edwuard Makuka, who ran a training program that aimed to send two cats, a missionary, and one woman into space. It calls black space tradition into the exhibition, which is otherwise very white.

Most joyous is Swedish

artist Aleksandra Mir’s film First

Woman on the Moon

(1999). In bright

color, we see cameras set up over a Dutch beach that has been landscaped to

resemble craters and boulders. A woman climbs to the top of a dune and plants

the American flag, before a party breaks out and children start to play in the

sand. The adults gather in little

gangs, clinking their drinks in celebration of this miniature feminist parody

of the time men claimed the moon as their own.

No woman has ever set foot on the moon. This thought had never occurred to me before seeing Mir’s film. But then I remembered last year’s First Man, which showed the ten years of Neil Armstrong’s life prior to the moon landing. As Armstrong, Ryan Gosling delivers a performance almost choked by the restraints of American masculinity of the 1950s and ’60s. In his short-sleeved white shirt and narrow black tie, Armstrong watches his daughter Karen die of a brain tumor and then never speaks about it to his wife again. His face stays rigid in public. He can only process emotions through space. At one stage he literally stands in his backyard and looks through a telescope at the moon instead of replying to his wife.

The life of Armstrong stands in such fascinating tension with the way people have imagined the moon in the past. The moon was feminine, overwhelmingly powerful, and a vast imaginary expanse where anything might be possible—he trod on it. These are the most moving parts of the story of the moon landing, and they flow through Apollo’s Muse, too—the moments when we can look back at human beings exerting every ounce of effort they had, against technological constraints. The failures—walk quickly past the photographic portrait of the Soviet space dogs—are more touching than the successes.

Throughout it all, the moon remains exactly the same. This Fourth of July weekend, I looked at the crescent moon over a mountain ridge through a telescope, the fireworks going off underneath. Witnessing its incredible fixedness, realizing the moon has been there all along, watching you, unchanging, is a little bit like seeing God. It puts a lump in your throat—the same moon that Jimmy Stewart lassoed in It’s a Wonderful Life! The same moon Philip Larkin saw in his poem Sad Steps, when spying it through the curtains on his way “back to bed after a piss”:

One shivers slightly, looking up there.

The hardness and the brightness and the plain

Far-reaching singleness of that wide stareIs a reminder of the strength and pain

Of being young; that it can’t come again,

But is for others undiminished somewhere.

At the Met, this permanent witness gets to be witnessed herself, in an exhibition brief in length and rich in charismatic detail. A museum is a tiny thing compared to the moon, but some of her glory is reflected here.