Last week, the Supreme Court wrapped up a full term without Anthony Kennedy for the first time in thirty years. Liberals can sum up the experience in five words: It could have been worse. Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation last October marked an ideological turning point for the court, one that will reshape American lives for decades to come. But that shift has yet to be fully realized.

Roe v. Wade is still the law of the land for now. The justices blocked Louisiana’s clinic-closure law from going into effect in February and haven’t yet taken up an abortion-rights case on the merits, despite Justice Clarence Thomas’s strident protests. And while the conservative justices handed Republicans a major victory last week by ruling that federal judges can’t fix gerrymandered legislative districts, Chief Justice John Roberts also delivered a setback to the party’s efforts to pervert the 2020 census. There may be cause for relief for liberals today, but there is little reason for optimism tomorrow.

The star of this term was Roberts, who presided as both its chief justice and its ideological fulcrum. The court’s final day offered a testament to his influence. Roberts wrote the majority opinion in Rucho v. Common Cause, where the court ruled 5–4 along traditional ideological lines that partisan gerrymandering is beyond the federal judiciary’s power to remedy. That ruling will likely embolden Republican state lawmakers to entrench their legislative majorities even more aggressively after next year’s census, especially in the states already sliding toward illiberal democracy.

The day wasn’t as bad as it could have been. In Department of Commerce v. New York, the court handed a serious blow to the Trump administration’s campaign to put a citizenship question on the 2020 census. Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for a 5–4 majority with the court’s liberals, drew the obvious conclusion from the facts at hand: The administration’s sole articulated rationale for adding the question “seems to have been contrived.” It’s the first time the court has substantively ruled against President Donald Trump, who threatened to delay the census to give time for the Commerce Department to craft a new rationale for the question.

It might be tempting to think of Roberts as a swing justice in the footsteps of Kennedy and Sandra Day O’Connor before him. That would be a mistake. Conservative pundits often rail against Roberts for his vote to save the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate in 2012, and they saw last week’s vote on the citizenship question as more evidence of his apostasy. This would misread Roberts’s approach to American political power, though. His votes on campaign-finance laws and voting rights have structurally tilted American politics toward conservative political forces while preserving as much of the court’s public legitimacy as possible.

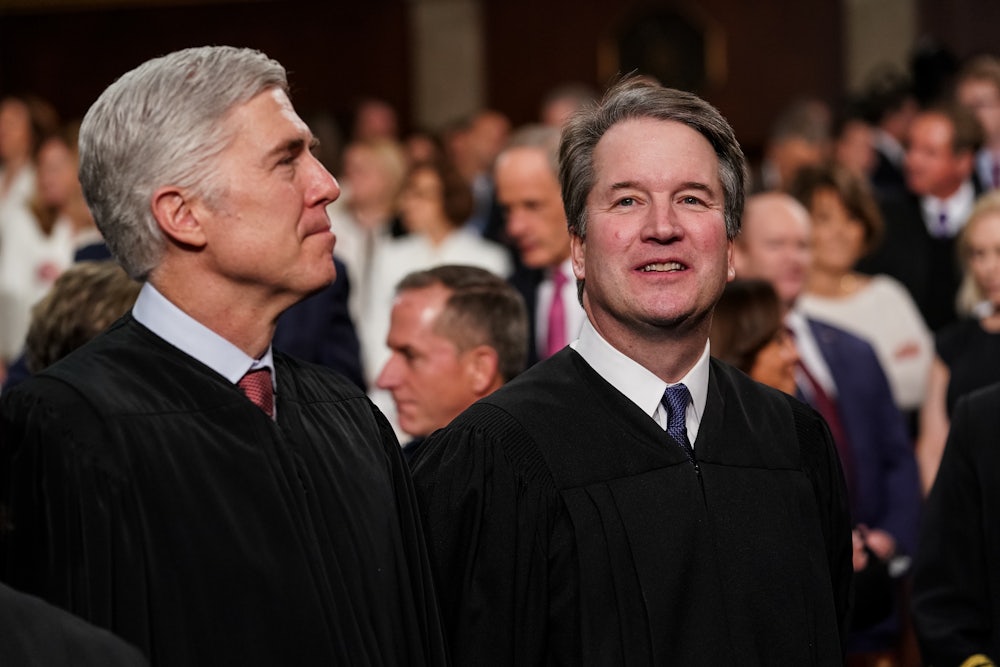

Kennedy largely joined those efforts, and Kavanaugh appears no different. Court watchers eagerly tracked the newest justice to divine how he would shape its trajectory in the years to come. As the term wound down, many of them remarked on the frequent divides between him and Neil Gorsuch, Trump’s other nominee to the high court. According to statistics gathered by SCOTUSblog, the two men only voted together in argued cases 70 percent of the time, the same rate he voted with Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan.

Those figures don’t mean Kavanaugh will become the next David Souter, a George H.W. Bush nominee who became a reliable member of the court’s liberal wing. Those same statistics show Kavanaugh voted 94 percent of the time with Roberts, for example. If anything, the numbers say less about Kavanaugh than they do about his fellow Trump appointee. Like Kennedy, for whom he once clerked, Gorsuch is more than willing to part ways with his conservative colleagues from time to time. Unlike Kennedy, Gorsuch tends to only part ways in certain types of cases.

Gorsuch’s libertarian streak, for example, often brings him in alignment with his liberal colleagues on criminal-justice matters. He routinely teamed up with Justice Sonia Sotomayor in Fourth and Sixth Amendment cases. In U.S. v. Haymond this term, he voted with Ginsburg, Sotomayor, and Kagan to strike down a federal law that allowed a judge to sentence the defendant to additional years in prison for violating the terms of his supervised release. That additional sentence, Gorsuch wrote, was unconstitutional because it wasn’t handed down by a jury. In a stinging dissent joined by the other conservatives, Justice Samuel Alito wrote that Gorsuch’s opinion “is not based on the original meaning of the Sixth Amendment, is irreconcilable with precedent, and sports rhetoric with potentially revolutionary implications.” Ouch.

The other area where Gorsuch is carving his own path is Indian law. Before joining the high court, he served on the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals in the Mountain West, where he built a reputation for fairness toward native peoples in litigation. Gorsuch provided the fifth vote for the liberals in Herrera v. Wyoming, where the court ruled that hunting rights guaranteed to the Crow Tribe by an 1866 treaty with the federal government survived Wyoming statehood. And in Washington Department of Licensing v. Cougar Den, he cast the decisive vote to uphold the Yakama Nation’s right to not pay a fuel tax under an 1855 treaty.

Along the way, Gorsuch showed a commendable respect for the tribes’ historical experiences. “Really, this case just tells an old and familiar story,” he wrote in his concurring opinion in Cougar Den. “The State of Washington includes millions of acres that the Yakamas ceded to the United States under significant pressure. In return, the government supplied a handful of modest promises. The State is now dissatisfied with the consequences of one of those promises. It is a new day, and now it wants more. But today and to its credit, the Court holds the parties to the terms of their deal. It is the least we can do.” Unfortunately, Gorsuch recused himself from Carpenter v. Murphy, the major death-penalty case that could restore tribal reservations over the eastern half of Oklahoma. The other eight justices, apparently hoping to avoid a 4–4 split in the dispute, scheduled it for reargument this fall.

While Gorsuch’s views in those areas are important, focusing on the cases where he doesn’t align with the conservative justices risks obscuring where he does. In two separate rulings, he signed on to his colleagues’ flexible approach to stare decisis to overturn major precedents on state sovereign immunity and on the Takings Clause. The two newest justices also joined Roberts’s majority opinion on partisan gerrymandering and dissented from his decision to block the citizenship question. Whatever idiosyncratic legal views Gorsuch and Kavanaugh might otherwise hold, Trump’s Supreme Court nominees both appear firmly committed to one of the Roberts Court’s great projects: maximizing conservative structural advantages in the American political system.

So, how did liberals form any majorities at all? Part of it is tactical. A defining theme of the Roberts Court is the four liberal justices’ willingness to stick together to achieve a five-justice majority in key cases. The conservative member would write the majority opinion, while the liberals would rarely file a concurring opinion that would create friction with it. Kennedy usually provided the fifth vote, but it wasn’t unheard of for Roberts or Antonin Scalia to join them either. This term was no different. Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan voted with each other between 82 percent and 88 percent of the time. Gorsuch, by comparison, voted with Roberts only 68 percent of the time and with Kavanaugh only 70 percent of the time.

But statistics only tell part of the story. Take the court’s ruling in Kisor v. Wilkie, for example. The justices took up the case to revisit what’s known as Auer deference, a doctrine whereby courts defer to federal agencies’ reasonable reading of ambiguous regulations. Conservatives hoped the court would use the opportunity to overturn the doctrine and give judges greater leeway to curb the federal government’s regulatory authority. In a 5–4 decision by Justice Elena Kagan, however, the court declined to overturn Auer. This time, Roberts provided the fifth vote.

That sounds like a victory, right? Except that a court with five liberal justices likely wouldn’t have taken up the case in the first place. And instead of upholding the doctrine outright, Kagan’s majority opinion added a five-part test that will give judges more room to scrutinize those regulations. And in a concurring opinion, Roberts wrote that the ruling had no bearing on the fate of the Chevron deference, a similar administrative-law doctrine that’s under siege by conservative legal scholars and judges. In a post-Kennedy Supreme Court, there are few permanent defeats for conservatives—and fewer permanent victories for liberals. Make no mistake, this is still a very conservative court.