The seriousness of Pete Buttigieg’s pursuit of the Democratic nomination for president is, in no uncertain terms, a stunning reflection of progress. It is remarkable that a gay man—one who lived through a time when his choice of sexual partner, his desire to marry, and his interest in adopting children were all contrary to the law—is a legitimate contender in the race to be commander-in-chief. Given that his success surprised me, an early-twenties gay millennial, I can only imagine the glee being felt by the queer Americans who lived through decades of discrimination far harsher that its contemporary analog.

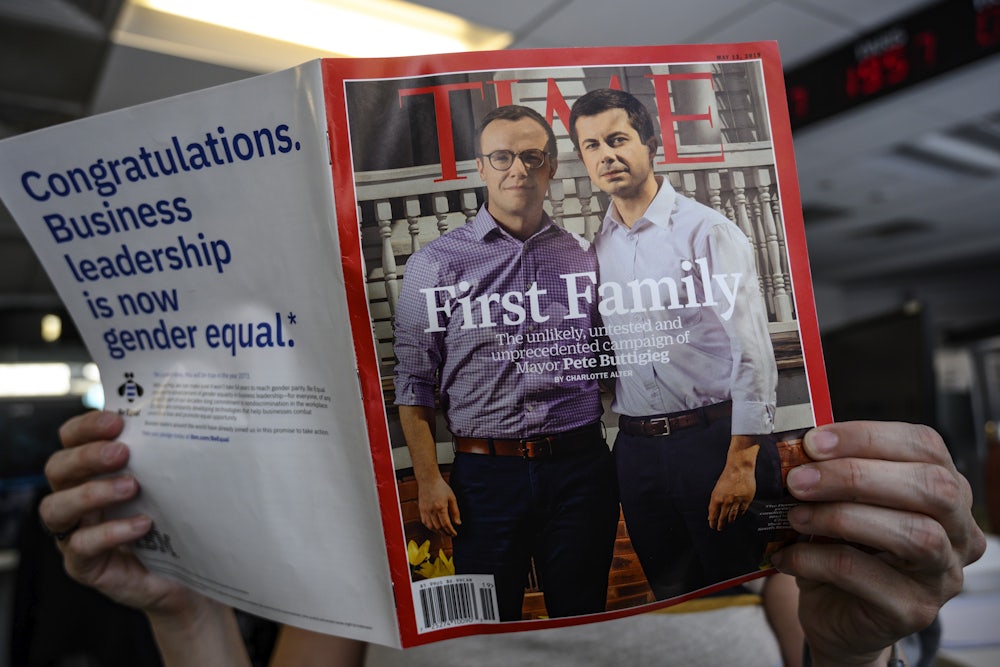

Buttigieg’s candidacy, beyond warming the hearts of this older generation, serves also to embolden their younger counterparts. Research by Jeremiah Garretson, professor of political science at California State University, East Bay, has shown that as exposure to queer people increases, so does the probability of supporting job protections for them. Garretson’s observations could apply to Pete Buttigieg and his husband Chasten, whose smiling faces appear regularly in mainstream media, sometimes even together to proudly offer a once-illicit kiss. The couple’s regular appearances on these platforms, including their recent TIME magazine cover, can serve to tangibly improve the lives of queer Americans.

And yet, Greta LaFleur, a Yale professor of American Studies who also directs the university’s graduate program in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, recently penned a Los Angeles Review of Books essay titled “Heterosexuality Without Women” deriding the couple. Citing their traditional appearance, LaFleur accused the mayor and his husband of leveraging heterosexuality in an effort to offer the American public “the promise that our first gay first family might actually be a straight one.” Amid unnecessary jabs—including an allegation of “sartorial doppel-banging” (sleeping with your own doppelgänger)—she essentially argues that the couple is too mainstream to truly be queer. Instead, they are tangentially heterosexual. Her article, which won support from other academics and writers, demonstrates how intersectional thinkers, amidst their well-intentioned efforts to raise up the voices of marginalized queer people, often needlessly sideline and diminish the queerness of their privileged counterparts.

Curiously though, LaFleur never defines “heterosexuality,” relying instead on descriptions of the Buttigiegs’s presentation. She conflates their traditionalism—their masculinity, outfits, and sexual modesty—with heterosexuality itself, reflecting a surprising indifference to the fact that queer people were long denied these traditions.

It’s not that these attributes are innately non-queer, as LaFleur seems to imply, but that discrimination long made them appear as such. Queer people once weren’t allowed to blend in. We couldn’t appear normal nearly anywhere in the country, as we were denied access to the rites of a traditional life, such as marriage, children, and socially acceptable couplehood. And while the fight for LGBTQ equality is certainly not yet won, queerness, once forcibly relegated to the realm of counterculture, has achieved in many ways a promotion to that of the mainstream. The de-ghettoization of queerness is demonstrated both by gay America’s decades-long shedding of its countercultural nature in favor of a more assimilationist approach, and Pride Month’s transformation into an extravagantly corporate affair. Given that even capitalism now affirms the mainstream’s affinity for queerness, it should come as no surprise that certain couples, like the Buttigiegs, feel increasingly entitled to cultural normality.

It’s worth recognizing and celebrating queer people’s increased freedom to assimilate in ways previously unimaginable. Same-sex couples, thanks to the LGBTQ movement’s staggeringly quick bending of the American moral arc, now have an easier path toward starting their own families and comfortably receding into the banality of family life. The U.S. has become more progressive, and more willing to endow its queers with enough tradition for them to secure some American normality. The Buttigiegs’s successful embrace of such tradition does not relegate them to some sphere of heterosexuality; it instead evinces this progress.

The queer liberation movement has long placed a primacy on autonomy, the notion being that queer people have the right to be themselves without fear of discrimination. But LaFleur, by heterosexualizing the Buttigiegs based on their appearance, regressively polices their behavior and infringes on this right. She seems to imply that queerness is irrevocably intertwined with one’s rejection of the mainstream, and that the Buttigiegs are less queer because they’ve refused this rejection. But they, like all other queer people, have the autonomy to present themselves however they see fit—without forfeiting their queerness.

Queer people can now increasingly be in the mainstream, and the Buttigiegs’s demonstration of that reality does not make them less queer. The couple, no matter how privileged, mainstream, or traditional they are, are two gay men presumably having gay sex. There is nothing heterosexual about this situation.

The queer liberation movement has victoriously diversified the ways in which one can be queer. Femininity-embracing drag queen Aquaria, traditionally masculine former NFL player Michael Sam, and presidential candidate Buttigieg can all be affirmatively gay. But there remains no “right way” to be queer: Aquaria is no gayer than Sam, just as the quiet gay boy who plays calmly with dolls is no gayer than his rambunctious gay counterpart who finds more comfort in the throes of chaotic outdoor play. And the Buttigiegs, in embracing a traditionalism queer people were long denied, are no less gay than their counterparts who opt to reject these traditions.

Queerness will never hinge on one’s presentation, political opinions, or the level to which one embraces or rejects the mainstream. Indeed, one of the greatest achievements of the last 50 years is that queer people have won the right to present ourselves and behave however we best determine. The Buttigiegs have the right to be traditionally married and conventionally masculine without facing the forfeiture of their queerness. Critiques to the opposite effect are regressive, and wholly contradict the tenets of liberalism—freedom and autonomy—that the queer liberation movement once closely embraced.