On a Saturday morning in early May, several dozen Central American migrants gathered on a stretch of concrete outside the El Chaparral border crossing, the main point of entry to the United States from Tijuana, Mexico. Most have brought suitcases, and despite the muggy weather, many come bundled in layers of their warmest clothing, just in case they’re sent to the hielera—U.S. detention centers kept so cold they’re nicknamed the “ice box.” Around 8:30, an official from Mexico’s National Migration Institute gets a phone call telling him how many people can make an asylum claim that day. Some days, it might be ten or more. Today, it’s three.

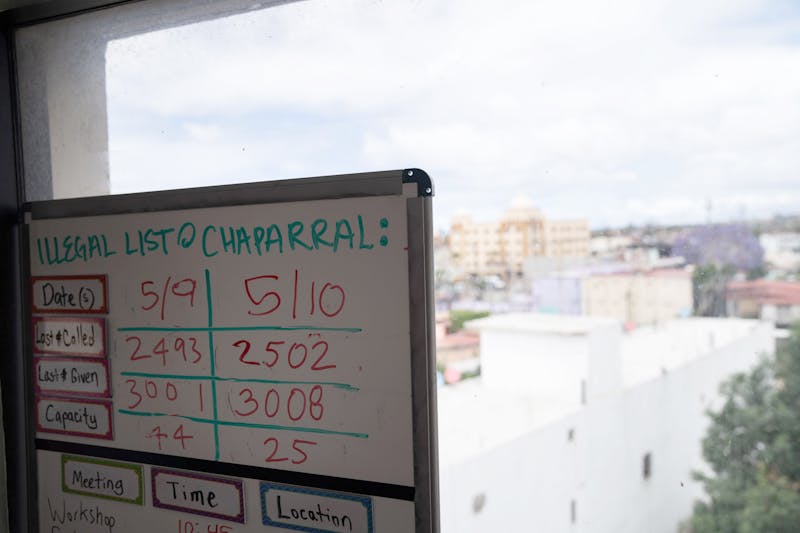

Since late last year, when the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) began restricting the daily number of asylum claims the U.S. takes, a queue forms each dawn at the border checkpoint. To manage the crowds, migrant volunteers started maintaining a handwritten, numbered list of asylum hopefuls. They take names at a plastic folding table under a tent, handing out numbers on thumbnail-sized slips of paper. That begins a months-long waiting period for migrants who, in most cases, have already been traveling for weeks.

When Mexican authorities give the volunteers word, they call out the day’s numbers over a megaphone. Today, some of those called aren’t present: Maybe they’ve gone home, maybe they’ve found another way to cross, maybe they’ve decided to stay in Mexico, maybe it’s something worse. Those who are there bid tearful goodbyes and drag their suitcases into a van that will take them over the border to U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) facilities where they can file their asylum claims.

This trip might be a final farewell, or the asylum seekers might find themselves back in a few days. Before the U.S. Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP)—also known as the “Remain in Mexico” policy—went into effect in January, what happened next was relatively predictable. Those requesting asylum would meet with an officer to make their claim; they’d undergo a brief interview and get an official “Notice to Appear” for their asylum hearing. They’d probably be sent to the hielera or to another detention center, or, if they were lucky, they might be released inside the U.S. until their hearing.

Now, for Central American asylum seekers, the path is more circuitous. After their interview, in which they’re assigned a date for their first asylum hearing, they might get sent to the hielera, or they might get sent back to Mexico, or to the hielera for a few days and then to Mexico. Each time they show up for court in the U.S., they could again be sent to detention or sent back to Mexico. (At any point in this ordeal, the migrants can decide to end the asylum process and sign a voluntary deportation back to their country of origin.)

As of early June, over 10,000 Central American asylum seekers have been sent back to Mexico after requesting asylum at the southern border. A federal appeals court temporarily blocked MPP in April, but in early May, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld the program, and the returns to Mexico started once again. After President Donald Trump threatened in late May to impose increased tariffs on Mexican imports if Mexico didn’t take drastic measures to reduce the number of migrants at the U.S. border, the two countries came to an agreement on June 7. The details are still open to debate, with Trump claiming he has a secret deal on a scrap of paper, but the spoken understanding is that Mexican officials will boost efforts to reduce the number of people heading north. According to a statement from the State Department, the U.S. will immediately expand implementation of MPP “across the entire southern border.”

MPP, a program ostensibly meant to protect migrants at the border, does just the opposite, making the already-labyrinthine asylum process even more opaque, and forcing those seeking asylum into a maddening and unpredictable cycle of entrances, hearings, detentions, and releases. The Trump administration justifies sending Central American migrants back to Mexico with the assertion that many seeking asylum fail to show up for their hearings if they’re released stateside, but statistics prove the opposite. As of 2017, nearly 90 percent of asylum seekers appeared at court for their hearings. Nevertheless, MPP requires many migrants wait in Mexico, making an already precarious situation even more dangerous.

In mid-May, the Tijuana list had around 5,000 migrants waiting for their turn to enter the U.S. and make their asylum claim. While these immigrants may have waited a month or two to seek asylum before MPP began, now, their time on the southern side of the border extends indefinitely. And every migrant in Tijuana is at risk in some way, especially if they aren’t Mexican, according to Luis Guerra, a consultant from the Catholic Legal Immigration Network. Guerra is working with the Border Rights Project and Al Otro Lado, one of the only organizations providing consistent legal counsel to asylum seekers in Tijuana. “They’re constantly being targeted by local law enforcement,” he said, “and because they’re stuck here, they are being sought out by their persecutors [from their home countries], and many have been found.”

“I’ve talked to people that are no longer alive.” Guerra said. “We know that many people have disappeared from Tijuana.”

Not all Central American asylum seekers are returned to Mexico after making their claim, but the rulings on who stays in the U.S. and who is sent back across the border appear arbitrary. When people plan to cross into the U.S., they usually expect to leave the Mexican border town for good. If they’ve had a job during their months there, they quit; if they’d secured a bed in a shelter or had rented a room, they pass it on; if they’d accumulated possessions, they sell them.

When asylum seekers return, said Guerra, their first concern is where to sleep. Many of the 30-odd shelters in Tijuana are currently over capacity. If someone leaves in the morning, the bed may be filled by the time he or she returns, even if it is just a few hours or days later. Beyond that, many need medical care for worsening physical conditions. (In some areas, chicken pox has spread through the cramped shelters.) Though migrants returned to Mexico may be better off than those who remain in U.S. detention centers, the challenges are similar—gaining access to legal counsel, the inability to work, the sense of stagnation—but in Mexico, migrants often face violence, discrimination, and harassment, as well.

The process, Guerra said, is designed to create confusion. Some people, on being returned to Mexico, think they’ve actually been deported. Others think they can’t appear at their asylum hearing without an attorney, something that is virtually impossible to find in Mexico. One couple who’d been returned to Mexico twice—after their initial asylum claim and their first hearing—found a photocopied list of legal services stapled to their Notice to Appear. All were based in San Diego.

MPP complicates the asylum-seeking process at every level. Jeffrey came to Tijuana from Honduras in November, and he entered the U.S. in early April to seek asylum. That day, he was assigned a court date—May 7—and was then sent to the hielera, where he spent five days before being sent back to Tijuana. When Jeffrey showed up at court on May 7, though, the judge didn’t have him scheduled for a hearing. (Guerra said this is now happening more frequently, due to lack of coordination between DHS and the courts.) Jeffrey was ordered back to Mexico, but DHS agents had taken his backpack, holding his passport, humanitarian visa, and documents he would need to prove the danger he faced in Honduras. Jeffrey told the officials he wouldn’t return to Tijuana without the backpack, at which point he was returned to the ice box for four more days. CBP then sent him back over the border with an empty backpack. His new court date is scheduled for August, ten months after his arrival in Tijuana, but he no longer has the documents he needs to request asylum. He doesn’t even have a way to prove his identity.

Jeffrey doesn’t feel safe in Tijuana. He was detained by police last month, accused of saying something crude to a woman, and they took 1,500 lempiras (around $60) from him. He says that other Central Americans he knows in Tijuana have routinely experienced this kind of repression from the police: Arbitrary arrests, extortion, accusations of nonexistent crimes.

The litany of detentions and releases works to wear asylum seekers down until they give up. Carmen came to Tijuana from San Miguel, El Salvador, fleeing threats after denouncing local gang members. When she entered the U.S. to seek asylum in March, she was six weeks pregnant. She was sent to the hielera, where, she said, she felt scared all the time. The food was expired, the conditions horrible. During her detention, Carmen said, she had a miscarriage. After 13 days in U.S. custody, she was released into Mexico once again.

Her first court date was a month later, and she was again detained for four days, then returned to Tijuana. Her next date is June 18. Meanwhile, she’s in charge of organizing the storeroom at the shelter where she’s staying. At this point, Carmen said, she doesn’t want to keep going though the process. She can’t safely return to El Salvador, though, and she doesn’t know how she could stay in Tijuana.

In the daily Border Rights Project talk that Luis Guerra gives to migrants in Tijuana, he tells people that getting asylum is like winning the lottery. Whether they’ll eventually get status in the U.S. depends not on the strength of their case, nor the severity of the threats they flee, but on the whims of the system. Some asylum judges have application approval rates in the single digits; others, over ninety percent. Asylum seekers can learn the steps of the process, or try to prepare themselves for their interview with DHS officials, or learn the legal ins and outs of the policies that will decide their fate. No one can tell them, though, how to win their case. No one knows whether they’ll be released into the U.S., or returned to Mexico, or kept for weeks in the hielera. No one can tell them just how long this cycle will continue. Everything is arbitrary. The system is broken; the system was built to break.