Jared Diamond doesn’t use a computer. He relies “completely” on his secretary and on his wife for “anything” requiring one, as he puts it. Diamond also confesses that he lacks the ability to turn on his “home television set” and can “do only the simplest things” with his newly acquired iPhone. “Whenever friends have shown me how to use a computer, they turn it on and something goes wrong,” Diamond once explained to an aghast reporter. “I just get frustrated.”

Such incapacities haven’t held Diamond back. Just the opposite. He has spent much of his career explaining and championing the “modern ‘Stone Age’ peoples,” as he calls them—cultures reliant on tools and practices dating back thousands of years. The most “vivid part of my life,” Diamond has written, was spent in “technologically primitive human societies,” especially the “intact” societies of New Guinea, where Diamond worked for decades studying birds. It was on one such ornithological trip in the 1970s that Diamond encountered a “remarkable” Papua New Guinean named Yali. Diamond met him by chance on a beach, the two walked together for an hour, and Yali—with a “penetrating glance of his flashing eyes”—asked a big question: Why did whites have so much and New Guineans so little?

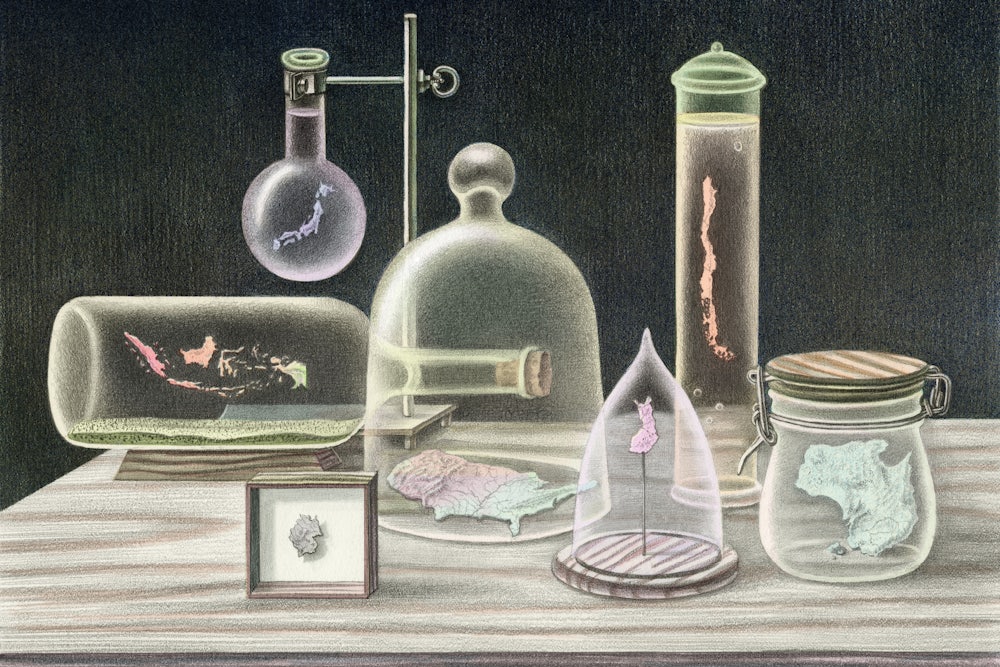

Diamond’s breakout book, Guns, Germs, and Steel, was his answer. It offered a sweeping survey of the past 13,000 years. Thinking as a scientist, Diamond searched for the variables that had shaped societies. Though he couldn’t run laboratory experiments on large human groups, he could find “natural experiments,” similar societies that differed in just a few crucial respects. Their divergent fates could illuminate the effects of those differences. Islands and other locales with a “considerable degree of isolation,” Diamond wrote, work best for this purpose.

On the scale of millennia, Diamond concluded, individual decisions don’t make much difference to the trajectories of societies. Environmental factors are far more important. Guns, Germs, and Steel emphasized the shape of continents. Eurasia’s horizontal axis allowed plants and germs to spread easily along latitudinal belts, endowing its inhabitants with large populations, powerful technologies, and fiercely contagious diseases (useful weapons in colonizing foreign lands). The Americas and sub-Saharan Africa, by contrast, run on vertical axes and produced smaller and less epidemiologically menacing civilizations. It was a reassuring conclusion, conspicuously rejecting racism and chauvinism in its account of nonindustrial cultures.

The book was stuffed with hundreds of pages of geography, epidemiology, and archaeology, and it presented virtually no characters besides Yali. Nevertheless, it caught fire, selling more than 1.5 million copies in dozens of languages, winning a Pulitzer Prize, and taking up a permanent perch in airport bookstores across the planet. It helped that Guns, Germs, and Steel was fun. Diamond offered charming explanations of why humans learned to farm almonds but never acorns (“slow growth and fast squirrels”), or why they ride horses but not zebras (nasty dispositions and a penchant for biting). Eight years later, Diamond produced a sequel, Collapse, studying mainly “small, poor, peripheral, past societies” that had fallen apart—the Norse in Greenland, and the ill-omened inhabitants of Rapa Nui, or Easter Island. These, too, he chronicled with palpable sympathy. “They were people like us,” he wrote. And perhaps, without care, we might share their fate.

Jared Diamond is back, now with the final installment of what his publisher describes as his “monumental trilogy.” Where Collapse explored places that failed, the new volume, Upheaval, asks about those that survived. It takes Diamond far from the sorts of societies where he’s felt most alive: the closed-off tribes, the “Stone Age” peoples. Upheaval examines such large countries as the United States, Finland, Japan, and Chile, and mainly in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Through them, Diamond hopes to show how nations have made it through destabilizing crises. But what we see instead is how poorly suited his approach—honed on nonindustrial and isolated societies—is for large, connected ones in an age of globalization.

If Yali inspired Guns, Germs, and Steel, the inspiration for Upheaval was Diamond’s wife, Marie Cohen, a clinical psychologist. Her work at a community mental health center in the first year of their marriage acquainted Diamond with factors that therapists have identified to predict whether a patient will prevail in a crisis. Diamond selects a dozen: acknowledging the crisis, accepting responsibility, defining the problem, getting help, having patience, and so on. The same twelve variables, he argues, can be applied with slight modification to nations. Examining seven cases, Diamond sets out to show how his factors account for countries’ ability to weather tumult.

Twelve variables, seven cases—this is the language of scientific history, the approach Diamond has long championed. A centerpiece of Collapse was his study of the effects of nine variables (such as temperature, moisture, and airborne volcanic ash) on island societies’ survival. Though Diamond’s high-velocity romps through history often vex specialists, this one earned him “high marks” from Patrick Kirch, a distinguished archaeologist of Oceania. Diamond had designed his study carefully. Nine variables were a lot, he acknowledged, so it “would have been utterly impossible to evaluate them without a large database and without the use of statistics.” He and his fellow researcher, Barry Rolett, began with the hunch that Rapa Nui’s storied collapse was environmentally caused. But without their careful statistical analyses of 80 other islands and similar locales, Diamond wrote, that guess “could not have been accepted.”

Past Jared Diamond, meet Present Jared Diamond. Whatever rigor Diamond demanded of himself in writing Collapse has been set aside in Upheaval. Now we have more variables (twelve), and significantly fewer cases (only seven). Worse, the variables, ported from the psychological study of individuals to the sociological study of nations, are unquantified and maddeningly hard to pin down. How to know whether a nation has “honest self-appraisal”? And how to balance the variable of “national core values” against “national flexibility”—wouldn’t one cancel the other out? Diamond initially sought to find ways to measure his variables and test their effects, as he’d done for his island study. But he concluded that this would entail “a large project.” And so, displaying a decided lack of variables 2 (accepting personal responsibility), 4 (getting help from others), and 9 (patience), he gave up.

What remains is a “narrative survey,” speculative and loose. Finland endures the Soviet Union. Australia sheds its white identity. Germany recovers from Nazism. The crises differ in type and severity. What unites them is that the nations in question survived.

Survival, it must be said, is a low bar to clear. Consider one of Diamond’s cases, Indonesia. Its crisis was that in 1965, two army units killed six generals in a coup attempt. The ensuing tumult gave the general Suharto an opening to push aside Indonesia’s left-leaning president, Sukarno. And the army inaugurated a massacre of some half-million suspected communists. Suharto soon took over, ruling Indonesia as a corrupt dictatorship for some 30 years.

It wasn’t all bad, argues Diamond, who worked in Indonesia for 17 of those years. The ousted Sukarno had been no saint, and, “neglecting Indonesia’s own problems,” he had “involved himself in the world anti-colonial movement.” Suharto, by contrast, was an “outstanding realist” who rightly “abandoned Sukarno’s world pretensions” and concentrated on internal affairs. His regime “created and maintained economic growth,” promoted family planning, and “presided over a green revolution.” And the subsequent years have given the country, Diamond notes, a “deepening sense of national identity.”

What accounts for Indonesia’s success, such as it was? It’s hard to say. The problem isn’t merely that Diamond has jettisoned statistical analysis. It’s that the crisp explanations that populated Guns, Germs, and Steel—the acorns, zebras, and continental axes—are missing. We learn that the government articulated core values, but that Indonesians, divided among thousands of islands and hundreds of languages, suffered a weak national identity. Indonesia identified its problems but at first lacked honest, realistic self-appraisal. Diamond isn’t noticeably wrong in those judgments, vague as they are; it’s just that he adds little to our understanding by them. It is hard to imagine a reader shouting “Aha! Core national values! Now I get why Indonesia’s economy grew.”

Lacking those eureka bursts, Upheaval settles into story time. There are joys here, particularly in Diamond’s historical accounts. He narrates Finnish guerrilla tactics against the Red Army in World War II with infectious glee (skis and white camouflage, it turns out, fare well against tanks). He applies a similar gusto to the tale of nineteenth-century Japan, crediting Japan’s “unifying national ideology” and realistic self-assessment with its mastering of Western technologies during the Meiji Restoration.

Yet the closer he gets to his own time and place, the less brightly this crazy Diamond shines. One problem is the basis of his authority. Diamond chose his case studies not for the insights they offer, but because they’re the countries he’s lived in (save for Japan, though Diamond reassures the reader that he has Japanese cousins and nieces by marriage). Rather than ground his pronouncements in the scholarship he’s read, he repeatedly invokes “my own first-hand experiences and those of my long-term friends.” His “friends” tell him that a coup against Chile’s elected leftist President Salvador Allende was “inevitable,” that Japanese teenagers text too much to date, and that U.S. venture capitalism succeeds because it takes bold risks. Those friends include senators, investors, and a member of the Dutch defense force in New Guinea—nearly all represent the elite of Diamond’s chosen societies.

Perhaps it’s not a surprise that the meandering accounts that follow offer mainly middle-class nostrums and bland conventional wisdom. Chile was right to proceed cautiously in punishing members of the Pinochet dictatorship. Japan should apologize more fully for World War II. Australia’s wines are delicious—Diamond recommends De Bortoli’s One, Penfolds Grange, and Morris of Rutherglen’s Muscat.

Upheaval’s final case is the United States, where Diamond worries most about the loss of compromise and civility. It’s a problem he knows well; a peer-reviewed scholarly journal recently ran an editorial titled “F**k Jared Diamond.” Yet reading Diamond on “declining courtesy” in elevators, the super-abundance of TV channels, and younger people’s obsession with their cell phones, one feels oneself less in the presence of a penetrating social theorist than a dyspeptic relative at the Thanksgiving table. As Bernard DeVoto once said of Margaret Mead: “The more anthropologists write about the United States, the less we believe what they say about Samoa.”

At the start of Guns, Germs, and Steel, Diamond identifies Yali as a “local politician” who had “never been outside New Guinea.” A reader, noting the pictures Diamond includes of New Guineans in traditional garb and reading his talk of “intact societies” there, might take Yali for someone bound by custom, a man with constrained horizons.

But that would be wrong. Yali had left his home—the Ngaing bush area of Sor—at a young age to work in a European-run hotel. He had been a sergeant in the colonial police, left his country, joined an intelligence unit of the Australian army, spent time on a U.S. submarine, led an insurrection, and served nearly six years in prison for “incitement to rape.” I know this because, eight years before Diamond met Yali, the anthropologist Peter Lawrence profiled him extensively in his classic study of cargo cults, Road Belong Cargo. In Lawrence’s telling, Yali was thoroughly enmeshed in an international economy and international politics. His time outside New Guinea—contrary to Diamond’s claim that he’d never left the island—had been crucial to his evolving political thought.

The difference between Diamond’s Yali and Lawrence’s Yali illustrates a key feature of Diamond’s oeuvre, one that has great bearing on Upheaval. Diamond has always been drawn to “isolated” cultures or those just on the cusp of contact with outsiders. They best suit the natural experiments methodology as he practices it, and they have been the reliable source of his most memorable material. But the other side of the coin is that Diamond has a noticeable habit of downplaying the external connections of the places he’s describing. Instead of Yali the anti-colonial leader or Yali the Allied intelligence officer, we get Yali the provincial New Guinean lowlander. It is, the geographer Alf Hornborg writes, an “atomistic approach,” one that looks at the world and sees only separate societies “managing their own destinies.”

That approach, perhaps appropriate for Rapa Nui circa 1500, falters when applied to modern countries. Again, take Indonesia. Surely, Diamond is correct that its national identity, core values, problem-solving skills, and self-appraisal mattered. But it seems bizarre to focus on these while saying so little about external factors. Most notably, Indonesia at the time of its crisis was a Cold War battleground. Both the United States and Soviet Union poured military aid into the country, while China egged the communists on. These powerful outside forces helped mold local political fights into a war over communism, and they intensified the resulting violence. “It is impossible to think of Indonesia in 1965–1966 outside of the Cold War,” the historian Bradley Simpson insists.

The broader context mattered for what came next, too. Diamond notes with satisfaction that Indonesia has calmed and prospered in the past half-century. But these are not unusual outcomes. The International Monetary Fund expects only 5 percent of national economies to shrink this year. Per-capita deaths from war—civil or otherwise—have diminished sharply since 1945. Indeed, the awkward fact about Upheaval is that the outcome it seeks to explain, persistence through change in modern times, is the overwhelming norm.

The sort of “we have no more food and are, in fact, all dead” collapse that Diamond described fifteenth-century Vikings suffering in Greenland is today extremely rare (and it’s not even clear Diamond was right about the Vikings). There is thus little surprise that Chile, Japan, Finland, Australia, and Germany survived their storms. What is perhaps surprising is that health, peace, and prosperity have on average risen dramatically in the past 50 years. But as these are global trends, they cannot be satisfactorily explained by many individual nations defining problems clearly or exhibiting “situation-specific national flexibility”—Diamond’s variables. To say that few societies have fallen apart recently is no guarantee of a tranquil future. It’s just that, if catastrophe lies ahead, we will almost certainly experience it not as “nations” but as a planet, at the scale where Diamond’s variables seem less relevant.

Diamond acknowledges the difficulty of applying his Twelve Habits of Highly Effective Nations to the world as a whole. Using the traits of individuals to diagnose societies is intellectually treacherous enough; using them on an entire species is worse. Does humanity exhibit enough unity to even have “core values”? In response, Diamond weakly offers a parable about bird-watching in the Middle East. Despite hostility between Lebanon and Israel, birders in each country have agreed to send warnings about large avian flocks heading into each other’s country, where they pose dangers for planes. This, Diamond cedes, “falls short of an agreement for all 216 nations constituting the whole world.” But it’s a start.

The first page of Diamond’s trilogy—his conversation with Yali—was memorable. The last page is not. “Crises have often challenged nations in the past,” Diamond writes. “They are continuing to do so today.” Fortunately, he concludes, summoning the final gust of wind like an undergraduate completing a term paper, “familiarity with changes that did or didn’t work in the past can serve us as a guide.”

That’s not wrong, but nor is it helpful. Diamond seems unsteady in a world illuminated by iPhone screens. Complex countries, global economies, and international politics strain his “nations are like people” view of things. You’re left with the sense that he was on firmer ground where he started, chatting amiably as he strolled along the New Guinean shore.