The polls were unequivocal. In 2016, two days before Michigan’s Democratic primary, the respected Marist poll predicted that Hillary Clinton would win in a landslide, with 57 percent of the vote to Bernie Sanders’s 40 percent. On the morning of the March 8 primary, James Hohmann of The Washington Post wrote, “Michigan should have been fertile territory for Bernie Sanders’s populist and protectionist message, but he’s expected to lose the Democratic primary there today by double digits.” That night is mostly remembered for the marathon coverage of a bizarre press conference in which Donald Trump, who had just won three primaries of his own, shamelessly hawked Trump Steaks and Trump Wine. But if TV viewers had squinted at the crawl, they would have noticed that Sanders was pulling off a stunning, poll-defying upset—defeating Clinton by 1.5 percent. At the time, Nate Silver called it “among the greatest polling errors in primary history.”

Polling meltdowns like the one in Michigan—where pollsters missed the mark by roughly 20 percentage points—should have chastened the journalists who printed flawed forecasts throughout the 2016 campaign, all the way up until the night of November 8. But political handicappers have about as much humility as Trump does. To take roughly one week in May, they produced such headlines as, “Biden dominates Dem rivals in new early primary polls” (Politico), “Warren’s rebound? Massachusetts senator gains footing in polls” (Fox News), and “Brutal new 2020 numbers for Beto O’Rourke and Bill de Blasio” (The Washington Post). What these stories didn’t mention is that today, seven months before Iowa, polls are about as accurate as a blunderbuss, and most pollsters know it. As Diane Feldman, a leading Democratic pollster turned consultant, put it, “I want the public to believe the news media, but they are blowing their credibility by overhyping the polls.”

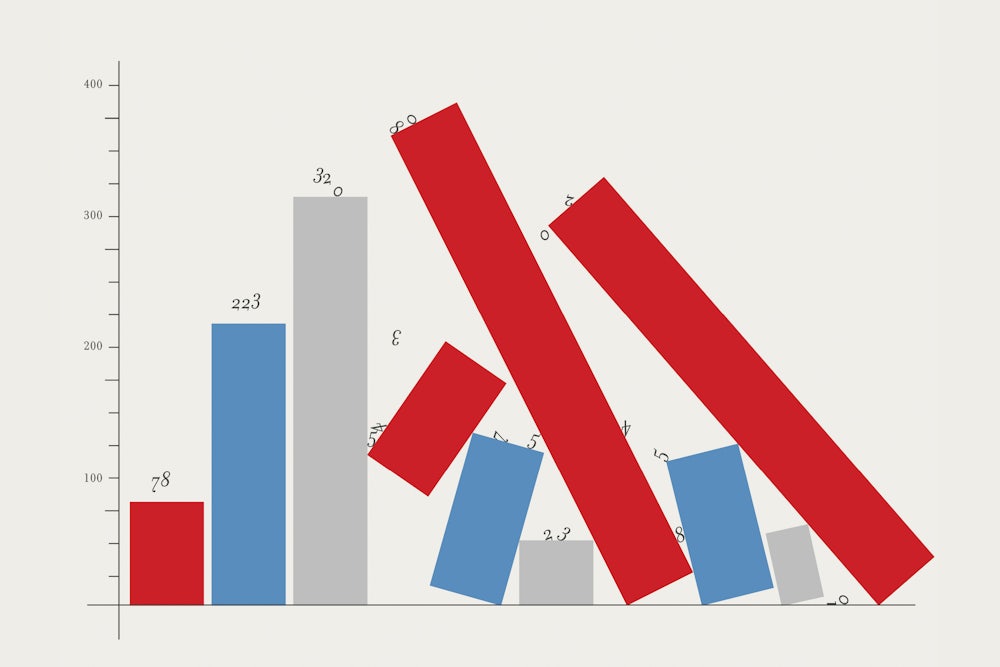

Why is polling in presidential nomination fights so unreliable? For one, no one knows who will vote. In Iowa, for instance, caucus turnout almost doubled from 2004 to 2008 (thank you, Barack Obama) and then dropped by more than a quarter in 2016. Second, a dwindling number of Americans answer phone calls from strangers, making it difficult for pollsters to get responses from an accurate sample. These problems are only compounded when the field is as sprawling and unruly as this one is. In late May, Monmouth University claimed that just 9 percent of Democrats were undecided. Really? Far more realistic were the findings from an April poll by the University of New Hampshire: 77 percent of Democrats in the first primary state are “still trying to decide.” To make matters worse, even the people who have made a choice can and often do change their minds. In 2004, Howard Dean held a hefty lead in New Hampshire until his candidacy unraveled in the Iowa caucuses.

To explain the wild fluctuations in their numbers, pollsters and their eager enablers in the press have created an artificial narrative of candidates bouncing up and down as if the campaign were conducted on pogo sticks. As Karlyn Bowman, a polling analyst for American Enterprise Institute, said, “Pollsters think that it’s good for business to have a new poll almost every morning.” Some are experimenting with online and texting polls. But until they come up with a reliable substitute, almost all of them are forced to fudge the numbers, artificially inflating the responses they get from, say, young voters.

The press pack, for its part, cannot shake its addiction to polls any more than candidates can resist the lure of TV cameras. Even if reporters could return to practicing retro journalism—divining the leaders, not with polls, but by talking to voters, county party officials, and other insiders—all those people are now glued to the polls, too, and their responses are as canned as an MSNBC talking head’s. We’re left with no other choice than to endure horse race journalism while the horses are still doing their morning workouts.