Senator Elizabeth Warren’s plan to address America’s opioid epidemic has one unusual component, something that sets her dramatically apart from nearly everyone else running for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination: a villain.

Specifically, that villain is Purdue Pharma, the creator of OxyContin. Even more specifically, it is the Sackler family, who own Purdue. A May blog post introducing Warren’s opioid plan promises “real criminal penalties” for pharmaceutical executives guilty of “dumping mountains of highly addictive pills” into struggling American communities. As part of the policy rollout, Warren campaigned in West Virginia, the heart of both the opioid crisis and “Trump Country,” to make the point directly to voters: “Look at families like the Sackler family; anyone heard of them?” she asked the crowd assembled in Kermit, a tiny town that had literally millions of hydrocodone pills delivered to its single pharmacy. “How do they make their big profits?… They sold [OxyContin] and they pushed doctors to write the prescriptions,” she said, delivering a brief summary of Purdue’s astonishing and shameless sales tactics.

It is not remarkable to hear a Democratic candidate go into populist mode while on the campaign trail, to rail against corporate fat cats and blame their greed for the problems facing blue-collar workers. It, however, is a bit unexpected—much more so than it should be—to hear one of them say the fat cat’s name.

Indeed, Democrats discussing society’s ills are almost pathologically averse to putting a name to the face. I remember hearing once about a young Democratic congressional staffer who was carefully admonished by a veteran aide never to call out drug companies by name when talking drug prices. The Democratic Party will acknowledge problems, but not villains.

It’s impossible not to notice how firmly this rule holds, once you’re clued into it. Senator Cory Booker, unveiling his campaign’s gun control plan, decried the NRA and even said “gun manufacturers” have behaved in “an ungodly way to undermine the safety and security of this nation.” He did not mention Smith & Wesson or Sturm, Ruger or any of the executives of the companies that have gotten rich manufacturing death.

Perhaps the funniest manifestation of this informal rule was when Andrew Cuomo, the Democratic governor of New York and a notoriously pugilistic politician, spent the better part of the first year of Donald Trump’s presidency essentially refusing to say the president’s name, out of the belief that it would be politically useful to avoid “picking fights” with him.

Most other Democrats at least have the sense not to extend that rule to their actual general-election opponents. But even when Democrats deign to declare that they are opposed to Republican rule, it frequently seems forced, as if they’re pandering to their supporters while secretly hoping their nonsupporters won’t get offended. At the heart of this predilection for the flight over the fight is a tacit ideology that is wildly out of step with the political reality of Trump’s America, where villains abound with almost comic ubiquity. And it is an ideology that, for the first time in living memory, is being challenged by an invigorated populist left, not only out of principle, but also out of a sense that the old way is naïve and ultimately self-defeating. The future of the Democratic Party, and by extension the country, may well depend on whether the party is finally willing to ditch its fretful posture of peacemaking and give war a chance.

The conventional wisdom on the Democratic side is largely predicated on a storybook version of the Democratic Party’s fall from grace and long, grinding return to power, undertaken by moderates rescuing the party from feckless liberals. According to this narrative, a long line of old-fashioned tax-and-spend liberals lost election after election until Bill Clinton and Robert Rubin made their peace with Reaganism, concluded that “the era of big government” was over, and unveiled a new politics that would strategically adopt conservative framing and even policy proposals in order to defang conservative backlash politics.

Barack Obama was an explicit critic of Clintonian triangulation, but he won election (so the story goes) on a message of unity, an affirmation that there was “not a liberal America and a conservative America” but one United States of America. Both men won two terms, cementing, in the minds of the consultant class, the essential correctness of their messaging styles. This, even though Clinton was impeached, Obama was hamstrung by an obdurate Republican minority, and Democrats ultimately saw the electoral devastation of their entire party down ballot at the hands of a political movement that believes very strongly in one liberal America and one conservative America.

The celebration of charismatic, conflict-averse uniters in Democratic-led White Houses omits a key, and punishing, shift in Democratic politics from anything resembling a viable effort to build a long-term majoritarian liberal coalition. Over the past two decades, Democrats steadily lost disaffected former supporters, while failing to consistently mobilize young or economically precarious people alienated from the entire political process, as the Republican Party increasingly became a nihilistic, anti-democratic machine designed to bamboozle a white elderly base and thwart the desires of the larger public for the sake of an entrenched oligarchy.

All the while, Democratic leaders continue to campaign and govern from a crouched, defensive position even after they win power. They have bought into the central ideological proposition, peddled by apparatchiks and consultants aligned with the conservative movement, that America is an incorrigibly “center-right” nation, and they have precious little strategy or inclination to move that consensus leftward—to fight, in other words, to change the national consensus; the sort of activity that was once understood as “politics.”

Consider just how deep-seated this reflexive inertia has become within the Democrats’ own leadership caste. At a 2015 Democratic presidential debate, Anderson Cooper asked the candidates an accidentally revealing question: “Which enemy are you most proud of?” None of them named an individual (well, former Senator Jim Webb sort of did, mentioning an “enemy soldier” he, uh, strongly implied he killed in Vietnam). Their answers were faceless evils like “the coal lobby” and “the NRA.” Hillary Clinton’s contribution, after “the Iranians,” was “probably the Republicans.”

It was a funny response for a number of reasons. First, because while Clinton had astutely mocked Obama’s theory of post-partisanship in 2008, the Clintonian approach of simply being 25 percent more Republican-like—voting for the Iraq War and supporting anti–flag-burning amendments out of some bizarre idea that doing so would cancel out the salience of those issues for the movement identified with nationalism and jingoism—had already definitively failed at either establishing long-lasting Democratic majorities or cooling the hysterical opposition of the right.

Second, because even though Hillary Clinton has absolutely every reason to consider Republicans her enemies, no one familiar with her record or biography really thinks she seriously considers them in such stark terms. She and her husband are longtime personal friends of the Bush family.

Even this jocular response—I’m proud that our political opponents intensely despise me—was too divisive for other members of Clinton’s own party. “I don’t consider Republicans enemies; they’re friends,” one Democratic elected official said in response. And he added, the next day, “I really respect the members up there, and I still have a lot of Republican friends. I don’t think my chief enemy is the Republican Party. This is a matter of making things work.”

That official was Vice President Joe Biden.

Now Biden is himself running for president, presenting himself as the bridge-building antidote to Warren’s unseemly naming-and-shaming. Here is Joe Biden’s theory of how politics works in the year 2019, as articulated at a campaign stop in New Hampshire just a few days after Warren’s West Virginia town hall:

The thing that will fundamentally change things is with Donald Trump out of the White House. Not a joke. You will see an epiphany occur among many of my Republican friends. And it’s already beginning … you are seeing the talk, even the dialogue is changing. So look, let me put it another way. If we can’t change, we’re in trouble. This nation cannot function without generating consensus. You can’t do it. What happens is, if you can’t generate consensus under our system of separated powers, all the power moves to the executive.

There’s an addled, half-remembered version of a coherent centrist analysis buried in there. The idea that the system cannot function without consensus is by no means an indefensible claim. But the modern Democratic Party has adopted it as a governing ethos, and it has led them to some weird places.

In Biden’s case, it has resulted in a perpetually amnesic structural critique of the conservative opposition. “This is not your father’s Republican Party,” he likes to say on the trail. He also enjoyed saying it on the trail in 2012. And in 2008. The reporter Paul Blumenthal tracked him saying it all the way back to 2006. Joe Biden is 76, not 13, so we can charitably imagine that the “father” he is referring to remembers a much older and different GOP. But if this hasn’t been that father’s party for an entire generation, how is the removal of Donald Trump supposed to break the fever?

One answer is, Biden is just telling people what they want to hear. Democratic voters, by and large, despise Trump, but also value a willingness to “compromise” in their own leaders. And portraying Trump as aberrant gives sometime Republican voters who don’t wish to feel personally implicated in the profound rot of the conservative movement cover to vote for Biden.

And all of that seems at least partly correct. But another answer is, Biden has nothing else to offer. He simply doesn’t have a model beyond consensus-seeking, which is why his camp is floating the absurd claim that Uncle Joe is the only candidate who can strike deals with the Democrats’ canniest enemy, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, when the record shows McConnell ruthlessly undermining the Obama White House’s ability to execute consensus-style governance at every turn.

The supporting evidence for Biden’s lack of imagination is, basically, the entire rest of the party’s elder leadership.

It’s easy to forget that Democratic leaders greeted Trump’s election by enthusiastically seeking to find common ground with him. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, who seemed to believe that he had some special ability to deal with Trump as his fellow New Yorker, spent the early days of Trump’s presidency insisting everyone would come together on some sort of infrastructure deal, even as literally millions of people marched on the streets in protest of everything Trump stood for.

Or at least, it would be easy to forget those overtures if Democrats didn’t again, this spring, post-Mueller report and everything, rekindle their old deal-making magic. As Politico put it:

By all appearances, they are mortal enemies. President Donald Trump has been at war with Democratic leaders in Congress for months, as the two sides trade subpoenas, lawsuits, and accusations of bad faith.

But on Tuesday, Trump, Nancy Pelosi, and Chuck Schumer did something few people expected: They got along—or at least pretended to.

All sides had apparently agreed on a handshake deal to spend $2 trillion on roads and bridges. As Politico alludes to, this is odd behavior for two parties seemingly “at war.” For dedicated liberals who’d listened to Democratic politicians refer to Trump, regularly, as manifestly unfit for office, corrupt, and a danger to our constitutional norms, watching them negotiate with him was enervating or enraging. And for what? A deal that Trump would get the majority of the credit for, leading into his reelection year. (The fragile accord for an infrastructure initiative fell apart right on schedule, when Trump demanded that Democrats halt all investigation into his administration’s staggeringly bountiful record of wrongdoing—when, in other words, the GOP executive predictably claimed his birthright of venting untrammeled anger at will, as feckless Democratic leaders looked on and shrugged.)

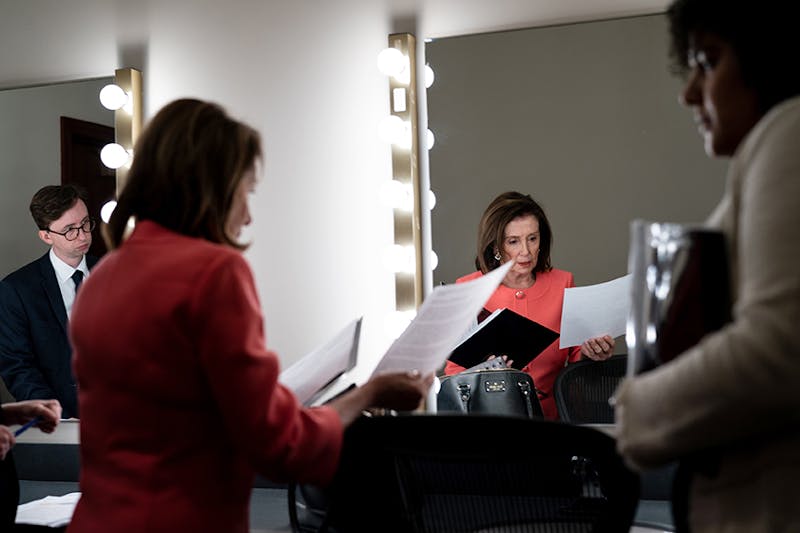

But such mediagenic theatrics concealed a far more momentous question: Had Trump and the Democratic leadership really been at war? Democrats first outsourced their attempts to fight Donald Trump to the office of Robert Mueller. Then, given a House majority with which to investigate the administration, they found themselves totally stymied by Trump’s stonewalling. How should they deal with an administration that refuses to answer subpoenas, whose White House counsel argues Congress has no constitutional right at all to investigate a president or his administration? Speaker Nancy Pelosi has been answering that question pretty consistently: Wait for the Trump administration to go away on its own.

She has almost complained that Trump has committed so many acts of malfeasance that he’s goading Democrats into impeaching him, and warned that they shouldn’t take the bait. “The president is self-impeaching,” the AP reported her saying in a private caucus meeting. “He’s putting out the case against himself. Obstruction, obstruction, obstruction. Ignoring subpoenas and the rest.”

Pelosi and her allies’ opposition to escalation in this largely one-sided war quickly reached comic heights. By the end of May, she was arguing that she was declining to open an impeachment inquiry into the president out of love of country. When a caucus argument broke out over the White House leaning on former counsel Don McGahn to ignore a subpoena to testify, Pelosi stood firm: “This isn’t about politics at all. It’s about patriotism. It’s about the strength we need to have to see things through,” she said, according to Politico.

There’s the bizarre anti-politics of center-liberalism stated plainly: that the American people don’t want to see conflict, and so therefore you mustn’t be seen as being responsible for it. Pelosi and her allies believe they are nobly withholding from their base (which they define as being distinct from “the American people”) the sugar high of aggressive oversight, for their own good. There is no sense that a new political reality can be forged, even with a foil as corrupt and unpopular as Trump.

As Representative Hakeem Jeffries, a Pelosi ally, said: “We did not run on impeachment, we did not run on collusion ... so logic suggests that we should carry forward with the agenda that we communicated to the American people.” The American people did not send Democrats to the House of Representatives to do politics, despite what it may have looked like when millions, very much inspired by their antipathy to Trump, voted to send a large Democratic majority to the House in 2018.

And so the response of congressional leadership has been: infrastructure week. They would not be tricked into treating the administration as an opponent to be fought and defeated. They would find compromise.

This amounts to a bifurcated bit of political messaging in which Trump is the unique problem preventing congressional Republicans from negotiating in good faith—the thing, we’re all serenely assured, that President Joe Biden will do with Mitch McConnell, in a burst of centrist fairy-dust magic. Meanwhile, congressional Democrats are jostling themselves eagerly within range of TV cameras to be seen negotiating in good faith with Donald Trump on deals whose inevitable later collapse they will then blame on the extremism and intransigence of Mitch McConnell and congressional Republicans. It’s almost as if all this good faith negotiating is not exactly being carried out in good faith.

But if the messaging here seems flatly contradictory, it makes a rough sort of sense in terms of consensus-seeking politics. In all these cases, the solution to Republican extremism is the removal of bad actors, and not the political defeat of the dominant mode of conservatism—which is now thought impossible, despite its having been achieved (temporarily, as all political victories are) in the past. It’s as if the ultimate lesson of the collapse of the New Deal order is that it was a miracle that can never be repeated.

After we talked politics and populism over beers a while back, one longtime veteran of left-leaning organizations left me with the words, “Read Mouffe.” Chantal Mouffe, a left-wing political theorist from Belgium, has diagnosed this fixation on consensus above all else as a failure of liberalism. She writes, “A well-functioning democracy calls for a confrontation of democratic political positions,” and says a political culture that seeks to tamp down those confrontations causes people to reject liberal democracy altogether. “Too much emphasis on consensus, together with an aversion towards confrontations, leads to apathy and to a disaffection with political participation,” she says. It’s a conclusion that might ring all too familiar to Democrats who saw many disillusioned voters sit out the election in 2016, disappointed that the top of the Democratic ticket didn’t present a genuine alternative to oligarchy as usual.

Mouffe’s work deals with how to channel the inherent antagonism of democratic society into healthy democratic politics—i.e., how to ensure that “we share a common allegiance to the democratic principles of ‘liberty and equality for all,’” while acknowledging that we are in a fight over what those principles mean when put into practice. I bring up Mouffe because she has become an extremely influential figure in the new populist European left, and a small band of organizers and activists is trying to import her ideas here. It is not a coincidence that one of the few American interviews with Mouffe, which was published in The Nation in 2016, was conducted by Waleed Shahid, who is currently the spokesperson for Justice Democrats, the grassroots PAC that helped the insurgent campaign of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez defeat establishment Democrat Joe Crowley in New York.

In America, you can plainly see that the right has a muscular and coherent “antagonistic” approach to politics. They name enemies freely and tell their supporters how they will defeat them. They tell stories with villains: that George Soros is sponsoring an immigrant invasion, or that, somewhere in the brackish backwash of the 1960s, Frances Fox Piven and Bill Ayers created Barack Obama as a sort of socialist Manchurian Candidate.

The right’s fondness for conspiracy-inflected scapegoating is one of the things that has traditionally scared liberal Democrats away from a politics that clearly defines one’s opponents: At some point, between the New Deal and the Reagan Revolution, they internalized a belief that the end point of that sort of politics is totalitarianism. (David Sessions explored the source of that liberal tendency, as expressed by consummate liberal Adam Gopnik, in the June 2019 issue of this magazine.) But the aim of left-populists following Mouffe is not bloody revolution or a leftist version of QAnon. It is the expansion and radicalization of small-d democracy, which they believe must be used to fight the power of entrenched oligarchy—a power, embodied by people like Trump, that liberalism has utterly failed to deal with.

In a funny development, and in direct response to how the liberal establishment has failed to stop or rein in Trump, a lot of Democrats and liberals who probably haven’t read a word of Mouffe have stumbled onto a folk wisdom version of some of her central insights: that division cannot be “reasoned” away, and that successful politics requires the articulation of an enemy. (That is to say, an “enemy” in rhetorical terms. Mouffe says the challenge for pluralist democracies is to turn a “friend/enemy confrontation” into “a confrontation among adversaries,” which allows “confrontation to take place within democratic institutions” instead of playing out as civil war.)

This conception of politics has come to dominate the discussions on Pod Save America, the hugely popular liberal podcast hosted by a quartet of Obama administration veterans—not exactly left-wing insurgents. Slate’s Isaac Butler noticed this shift as it happened, writing last year: “Early on, there was the occasional tut-tutting about ‘polarization,’ but now the Pod Save America crew wants the Democratic Party to hit hard, to experiment broadly, to run the most progressive electable candidate in each district, and to refuse to compromise.” Pod Save America’s affiliated web site, Crooked Media, is edited by former New Republic senior editor Brian Beutler, who regularly excoriates Democrats for their failure to fight the Republican Party, and Donald Trump, more vigorously. (I asked Pod Save America host Jon Lovett, “the funny one,” if he’s ever read Mouffe. At the time this story went to press, I had not heard back.)

You can see the growing Democratic divide between antagonism and conciliation in the dozens of people running for the Democratic nomination. There is Biden, who promises to sit down with McConnell and a GOP in post-Trump recovery and negotiate deals, and there is Warren, who has made it clear that she believes her ambitious agenda requires reforming government and making it more democratic and responsive to people—by eliminating the electoral college, for example, or taking a look at how to disassemble the Senate’s de facto 60-vote threshold to pass legislation.

The stark differences in Biden’s and Warren’s records are part of why this is commonly painted as an ideological divide, with the “left” on the side of fighting and the “moderates” on the side of compromise. And that is broadly true of their overall projects—the left wants to overturn the order of things, which will take a fight, while the center wants to return to the pre-Trump status quo, which won’t. But adversarial politics aren’t the sole domain of the left, nor does everyone who wants to fundamentally reshape the country subscribe to them.

Take Cory Booker, who seems like an obvious addition to the “moderate” bucket because he is, constitutionally, a consensus-finder. He deplores the idea of naming adversaries, a tendency memorably displayed when he went on Meet the Press in 2012 and bemoaned the Obama campaign’s (fairly mild) attacks on private equity—attacks that happened in the context of Obama attempting to win an election against a former partner in a private equity firm. But Booker’s actual policy agenda is not noticeably more “moderate” than most of the rest of the field, and he has a genuinely progressive vision for his signature campaign issue, criminal justice reform.

(That issue in particular has attracted a parade of consensus-driven liberals, who believe they have found, in the libertarian right, a movement with which they can negotiate in good faith. They applaud any reform bill that, in a slightly watered-down form, makes it to the president’s desk. And the president, representing the libertarian right’s political coalition, appoints authoritarians to every federal law enforcement agency, expands and empowers the internal deportation force, and deploys the armed forces on domestic soil for nakedly political purposes.)

Or take Bernie Sanders. His politics are distinctly Mouffe-ian. His goal is to create a “we the people” and mobilize them to take on the oligarchy (or as he prefers to call them in stump speeches, “millionaires and billionaires”). But, as his liberal critics frequently note, he is often quiet on the small-d democratic reforms (he is not enthusiastic about eliminating the filibuster, for example) that will be necessary for his left-populism to have any chance at success within our decrepit constitutional system, and he’s less inclined than Warren to personalize his villains.

It’s not that he’s unwilling to “name names”—he has attacked the Walton family’s wealth and JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon’s successful regulatory capture schemes. But they’re all interchangeable cogs of oligarchy to him. (Wolf Blitzer grilling Sanders on CNN about his Dimon criticisms in 2012: “Because as you realize, I’m sure you agree, until now Jamie Dimon has had a sterling reputation as one of the most brilliant guys on Wall Street.” Sanders: “It is not Jamie Dimon. It is the absurdity of having those people who are supposed to be regulat[ed] doing the regulating.”)

And despite his reputation for standing alone, he’s spent decades building (working) relationships in Congress, where, if he never managed to pass much in the way of major legislation, he was still known for his ability to attract Republican support for amendments focused on his priorities. Sanders’s enemy is a class, not the individuals of the opposition party.

The differences in Warren’s and Sanders’s approaches were made clear when both were invited to hold town halls on Fox News. Sanders accepted, and turned in a performance in April that perfectly showcased his political strengths. He got the crowd—the Fox News–selected crowd—to give a show of approval to single-payer health care. He was open and polite to the members of the audience, and appropriately sarcastic and dismissive of Fox’s disingenuous moderators. He took his message directly to an audience that otherwise would hear only a skewed version of it—and showed that it is actually popular.

Fox invited Warren a month later. She refused, with a pointed statement that painted Fox News as a tool of the plutocrats. Fox, she wrote, is “designed to turn us against each other, risking life and death consequences, to provide cover for the corruption that’s rotting our government and hollowing out our middle class.” And, she pointed out, the Democratic town halls, which regularly scored large ratings, were urgently necessary for Fox’s bottom line. “A Democratic town hall gives the Fox News sales team a way to tell potential sponsors it’s safe to buy ads on Fox,” she said.

Warren is, of course, correct. Fox News is a poisonous influence on our society, a propaganda organ that irresponsibly foments racial hate for the sake of a media baron’s bottom line. It’s also defensible for Sanders to turn that media baron’s weapon against him for an hour. Even if their respective quasi-populist projects led them to different decisions, they do better on these questions than nearly every other Democrat, because both of them understand not to conflate Fox the product or Fox the business with the audience, and both of them seek to win over at least a portion of that audience. (It would be surprising if that crowd in Kermit, West Virginia, that cheered on Warren for attacking the Sacklers didn’t include any regular Fox viewers.)

Then there’s Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, a candidate whose appeal at first seems extremely shallow (young, credentialed), but who also quietly scrambles many of these categories. He’s resolutely opposed to pinning down his own ideology, but he freely tells reporters about his radical process agenda. He explicitly rejects compromise with Republican politicians, telling Ezra Klein that “any decisions that are based on an assumption of good faith by Republicans in the Senate will be defeated,” and telling Klein’s Vox colleague Zack Beauchamp: “In recent times, appealing to Republican legislators has been wasteful because they’ve mostly been acting in bad faith.”

Buttigieg also supports a grab bag of democratic reforms, like filibuster elimination and altering the makeup of the Supreme Court to loosen the GOP’s death grip over the judicial branch. These measures have the potential to fundamentally change American politics. The question he can’t answer is, to what end?

Buttigieg also fluently speaks the language of Obama-style centrist comity. He says he appeals to Republican voters by “focusing on results and making common-sense arguments,” and insists on prioritizing “values” over “policies.” And when Pete Buttigieg did his own Fox News town hall, shortly after Warren declined hers, that was very much the mode he operated in. He was heavily autobiographical, as usual, and light on policy detail, as usual. Where Sanders couldn’t hide his contempt for his hosts, Buttigieg had moderator Chris Wallace essentially eating out of his hand by the end of the broadcast.

Ironically, Buttigieg’s father, Joseph Buttigieg (who died just this past January), was perhaps America’s foremost scholar of Antonio Gramsci, and Gramsci, as it happens, is one of Chantal Mouffe’s greatest influences. Her theory of politics is heavily indebted to Gramsci’s writings on hegemony—i.e., the political and institutional forces that determine what a society considers “common sense” to begin with. Mouffe’s left-populism seeks to create a new hegemonic order, to change what “common sense” is in the same way Thatcherism and Reaganism did.

It’s hard to imagine Buttigieg seeking to upend the status quo so dramatically. After all, this is a candidate who went to work for the mega-consulting firm McKinsey—which in recent months has been accused of advising the Sacklers on how to “turbocharge” opioid sales—to, he claims, see how money works. Mayor Pete seems to be the candidate of “the problems are bad, but the hegemonic forces that produced them … those are very good.”

But the new populist left shouldn’t assume their monopoly on the language of fighting will last. Biden himself recently fantasized about “beat[ing] the hell out of ” Trump. In Biden and Buttigieg, we see two forms of a sort of centrist populism. I’m gonna punch you in the mouth until you make me compromise, on the one hand, and, on the other, a long march through the institutions carried out by the institutionalists themselves. Both represent a misunderstanding of the argument, a shift from answering the question of how to win a political fight to one of how to win an election. But like many such strictly procedural approaches to political power in America, neither approach seems to connect up very convincingly with the actual conditions of living, getting by—or fighting for what one believes in—in these United States. It’s enough to make one wish for self-impeachment.