No one can doubt that when the Allied soldiers went ashore on the coast of France on the morning of June 6, the last phase of the war began. In all probability it will still be long and bloody; indeed, the first days on the beaches were far more costly than most Americans, judging by the early complacency of press and radio, seemed to realize. Nevertheless, it is impossible not to believe that the Allies will win in the end, both over Germany and Japan. The English, quoted by Richard Lee Strout in this issue of The New Republic, are correct when they say that the question is not who will win the war, but how long it will last.

The invasion itself is of course only one in a series of operations under the grand strategy of the Allies, including the landings, in North Africa, the supplying of Lend-Lease materials on a great scale to Russia, the bombing of Japanese-held islands and the operations in Burma. Nevertheless, the first landings on the French coast had a psychological value greater, in all probability, than anything else in the whole war, including even Stalingrad. For those landings were the final nail in the coffin where lies buried the myth of German invincibility.

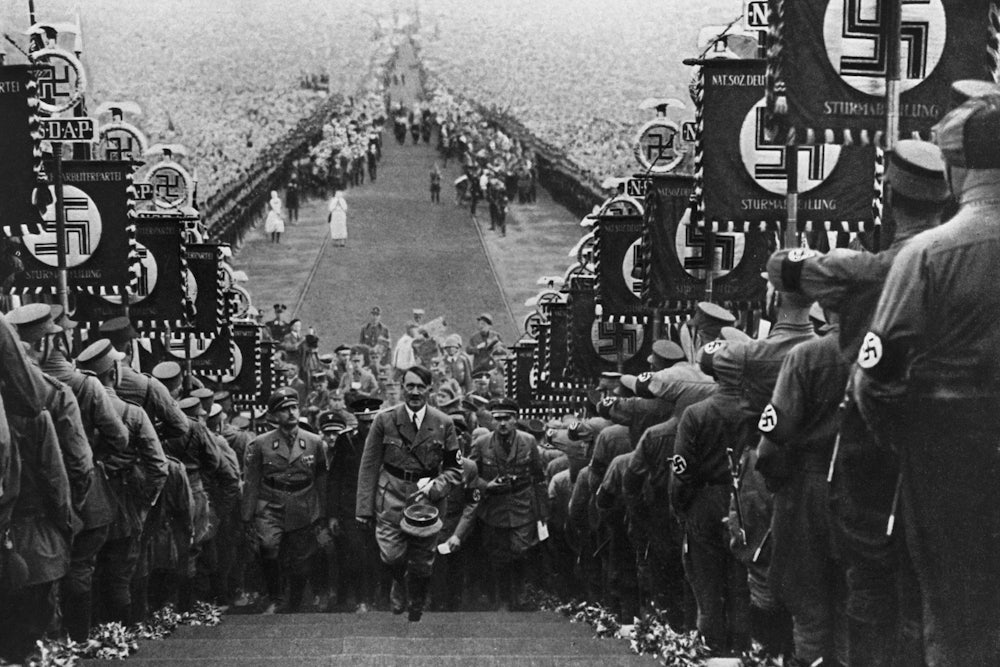

Sensible people throughout the world never for one moment accepted the Nazi doctrine of “Aryan superiority.” They were well aware that the scientists who study anthropology and allied subjects know that in its potentialities one race is the same as another. Yet all of us have a tendency to believe any statement made often enough and in a sufficient number of ingenious forms; and at the beginning the Nazis were extremely skillful in spreading the notion of their efficiency, ingenuity and resourcefulness. Before the war, German chemical science and electrical and metallurgical technology were known to be highly developed. In the early days of the war, when they were picking off, one by one, small nations which were without proper defenses, but could not have held out long even if they had had them, the Nazis gave a good imitation of practically irresistible power. It is hardly surprising, then, that we overrated them for so long. A majority of the professional military experts of the United States gave the Russians only six weeks or two months, after the German attack. And no matter how many times the stories were proved untrue, each additional German announcement of terrifying new secret weapons was likely in those days to send a chill down your spine.

But now, and for the first time, the German military machine has been deflated down to its actual size. As the fighting before Cassino in Italy and on the Cherbourg Peninsula have demonstrated, the Germans are still tough and resourceful; but that is all that one can say for them. On the ground they appear no better, man for man, than our own ground troops. In the air, the consistent record proves that our fliers are better both as pilots and as gunners. But most of all, the Nazi myth of an invulnerable Westwall has been shattered. After the Dieppe raid. Hitler boasted publicly that the “military idiots” who opposed him would never again be able to set foot on the European continent for as long as nine hours. Well, Hitler has been proved once again to be a liar. His Westwall was formidable in some places, much less so in others. But over a stretch of fifty miles, Americans, Canadians and British have stormed all his bastions, the strong and the weak alike, paying in each case whatever was the necessary price in blood. Long before that, of course, they had breached his fortress walls in Italy. To say the Westwall was a hoax would be a cruel injustice to the gallant soldiers of the United Nations who have given up their lives in crossing the sands, scaling the cliffs or dropping from the skies by parachute or glider to effect the bridgehead. The point is that at long last and after all our hopes and fears, we have gone ashore and stayed there. In spite of the precarious position in which we still find ourselves, it is impossible to believe that we shall lose our bridgehead, or shall be unable to establish others—perhaps many of them.

The myth of German power which finally came to an end on June 6 had already, of course, been badly damaged at Stalingrad and during last winter’s long retreat of the “supermen” westward into Rumania and Poland. The most industrialized nation in Europe had been beaten at its own game of industrialization for war purposes, partly by British and American factories, but mainly, so far as the Eastern front is concerned, by the power of once despised Russia. The humorless fanatics with blazing eyes who goosestepped so triumphantly across Europe winning victories against enemies one-tenth as strong as themselves offer a different picture when they fall back ignominiously before a foe who meets them on substantially even terms.

With the death of the Nazi myth of invincibility, fascism itself died in this world. It was a doctrine that had to be successful or it was nothing. You cannot argue that the world belongs to you because you are strong, and then demonstrate publicly that those you assumed to be weak are stronger than you are. You cannot argue that the lie is justified because it works, in the presence of overwhelming testimony that the truth has worked, and is working, even better. You cannot continue to prate about soft and decadent democracy in the face of a triumphant demonstration that democracy is able to fight at least as well as you can. The whole monstrous dream is now ended. To be sure, we may still have many months of heavy loss ahead of us; indeed, it is probable that most of the suffering, for our people, is still to come. But the danger, so grimly real two or three years ago, that the fascists would win, would control the world, and that all the fundamental decencies of Western civilization might be destroyed, perhaps for decades, perhaps forever—that danger has gone into limbo with the advance of our soldiers across the sands of Normandy.