Liberalism is under dire threat. On one hand, far-right parties are rising in Europe and a menacing American president is playing footsy with fascists and eager to pardon convicted war criminals. On the other hand, there are radical college professors and their shrieky students?

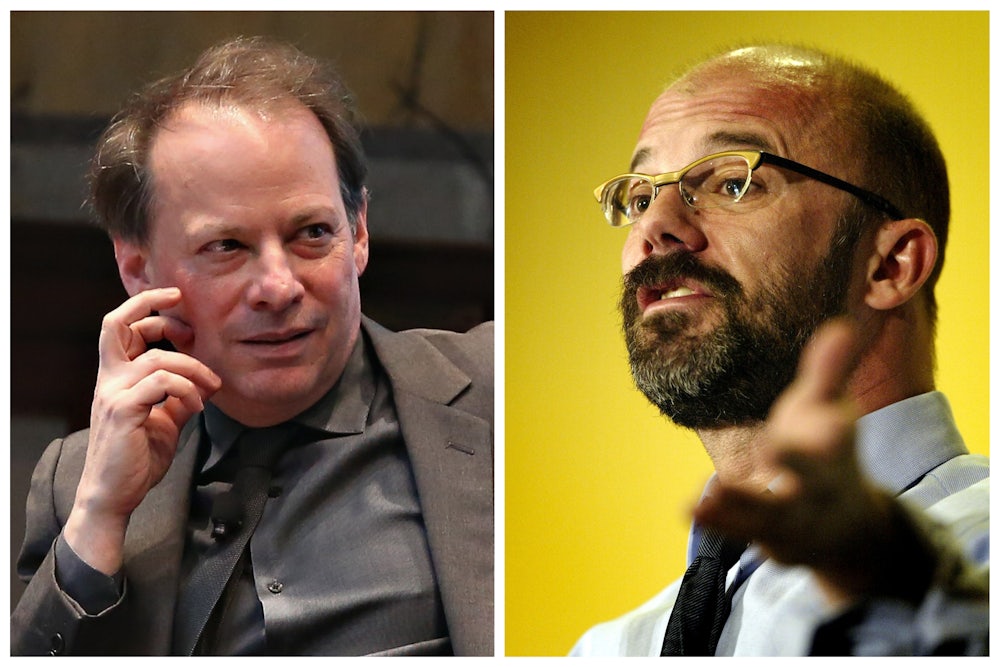

The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik and New York magazine’s Andrew Sullivan roasted that old chestnut of false symmetry to a crisp in a discussion on Wednesday at a bookstore in Washington, D.C. The occasion was a discussion of Gopnik’s new book, A Thousand Small Sanities: The Moral Adventure of Liberalism, in which he attempts to mount a “real and unapologetic contemporary defense of liberalism” against illiberalism from the right and the left. Sullivan, the long-time blogger and author (and former New Republic editor), is politically multicultural—conservative, gay, Catholic—and, by the end of the discussion, the one I’d rather have with me in today’s brawl against illiberalism.

In his book, Gopnik puts his signature genteel bohemian liberalism on full display. He rhapsodizes about how John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor’s marriage was a metaphor for the power of “compromise.” George Eliot and George Henry Lewes’s romance demonstrates how liberal politics come from individual “morals and manners.” Somehow, in Gopnik’s hands, liberalism ends up sounding less like a great political and intellectual tradition and more like a tortuous elaboration of The Beatles’ “All You Need is Love.” Not exactly the thing that will rally the troops against a force that is very good at identifying its enemies and acting accordingly.

Gopnik extols liberalism as the only self-correcting political system, but he doesn’t consider the possibility that liberalism itself generates the very forces—economic dislocation, social alienation, cultural malaise—that would destroy it. For Gopnik, there is no alternative to liberalism, and that leads him perilously close to circular logic. Nothing else “works,” so anything else will fail. The result is a bland complacency that seems impotent against such a dire threat, as he describes it. Gopnik writes that democracy flows “from the ground up, and as long as the space of common action [is] available, no one bad leader could affect it.” Strongman politics “is the story of mankind … it can always rise.” The causes of populism “are permanent … these passions … are always ready to explode.”

At the Politics and Prose bookstore, which he described as a “citadel of liberalism,” Gopnik was asked to consider the current political moment and he attempted reassurance. “Nothing is determined, nothing is fated,” he said. “We [also] should not over-invest in what I call ‘presentism,’ the belief that whatever’s happening now is going to go on continuing to happen indefinitely.” Gopnik didn’t attempt to resolve the tension between the two ideas. If the future is never certain, then it makes affecting the present all the more important. But if you also believe that things that are happening now won’t necessarily continue in the future, then it might absolve any urgency about acting now.

Sullivan does not suffer from Gopnik’s blasé affliction, and of the two seemed most interested in direct analysis of liberalism’s contradictions and failures. He shares Gopnik’s interest in social cohesion, though the two differed about the best source of cohesion. For Sullivan, cohesion comes from transcendental symbols and stories—i.e. religion, nationhood. Liberalism’s public square has “an empty center” that must be filled. “The fact that liberals do not have a language to speak about nationhood or borders or countries … has led to the far-right gaining power,” Sullivan said. The liberal worldview makes it “completely impossible to understand the country as a single unit.”

Against this charge, Gopnik was unconvincing. “Tolerance and pluralism” are liberal “community values” at work, he said. His real-world examples: the respective Cape Cod communities where he and Sullivan summer.

Sullivan probably had the sharpest point of the evening when he wondered if liberalism has worked only because of the prosperity it generated. What if it effectively “bribed” people who otherwise would not care to see the system continue? It was Sullivan, not Gopnik, who said that “the right-of-center has to come to terms with the failure of capitalism at this stage in making most people’s lives better.” Gopnik merely yearned for “remedial measures” to fix “the engine of prosperity.”

Sullivan decried liberals’ unwillingness to “fight back” against its enemies—especially, in his view, radical leftists. Gopnik, his voice reaching peak nasal vibrato, replied, “We don’t believe in fighting back, we believe in arguing and persuading and we’ll go on arguing and persuading and losing—until infinity.” Sigh.

The evening epitomized these disorienting times in American politics. It was the liberal who argued for maintaining or defending the status quo, and the conservative who recognized the necessity of change. With friends like Gopnik, liberals who don’t want to live in the past might have to make do with Sullivan.