It is easy to count the dead, harder to count the grieving. One has to estimate. Every year, almost one percent of the American population dies. The most recent available official count, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Vital Statistics System, is for the year 2017: 2,813,503 registered deaths. Looking at the numbers for 2014, Joe Biden calculated that each of those people “left behind at least one or two people who were deeply and profoundly wounded by the loss; some left a dozen bereft, others a score.” These bereft are the people who “get up every single day, put one foot in front of the other, and simply carry on.” If Biden has a natural constituency, it is to be found in this sad census of those who mourn. “There is an army of these soldiers,” he wrote in 2017, in his memoir of his vice presidency and of his own son’s death. “By my estimation, at any given moment, one in ten people in our country is suffering some serious degree of torment because of a recent loss.” The calculation conjures a great democracy of grief:

I see them at the rope lines at any political event I do, standing there, with something behind their eyes that is almost pleading. Please, please, help me. … So I try to be mindful, at all times, of what a difference a small human gesture can make to people in need. What does it really cost to take a moment to look someone in the eye, to give him a hug, to let her know, I get it. You’re not alone?

It is a shifting mass, this constituency, but all of us at some point join it.

To show my cards, I wish Biden were not running for president. His re-entry into politics makes all of us breathe stale air. The three matters most fully exhumed in advance of his announcement in April were his old stance on racial integration and busing in the 1970s (he opposed busing), his Senate committee’s vile treatment of Anita Hill during the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings of 1991, and his role in the “tough on crime” legislation of the 1990s. Biden evokes a past that is both close and far: far because these things were decades ago, close because they echo painfully, as if we have suddenly returned to that past or, worse, never left it. He will be called a “moderate Democrat,” a “centrist,” but beneath those misleading labels are specific and bitter issues we’ll have to parse, again, ad exhaustum. For such exhaustion to be worth it, one would have to believe that only a Biden presidency, above all others, would deliver us from political disaster. I am not convinced that it would. Nor would it deliver us from environmental collapse, the greatest disaster of all.

Biden’s “baggage”—an evocative shorthand for ideology, like it’s a suitcase we lug from train to train—is not unique. What is distinctive about him is not his politics but something more elusive: the chords of grief and mourning that he plays in the culture and that the culture hears in him. To show my cards again: Criticisms aside, I am moved by those chords. Few are so associated in the popular political imagination with intimate grief, and few have so fully claimed its territory. Biden’s entrance into and exit from national politics were marked by family tragedy. He was elected to the Senate in 1972, and a few weeks later his wife and infant daughter were killed in a car accident. In 2015, nearing the end of his vice presidency, one of the two sons who survived that crash, Beau, died from cancer. Biden named grief as the reason he did not seek the presidency in 2016. Grief and mourning shape his current campaign, too, in ways that are not easy to grasp. I suspect Biden himself has not fully grasped this mournful predicament. Nor has the great grieving public.

Biden was born in hardscrabble Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1942, to a family that imparted folksy wisdom and a salt-of-the-earth Golden Rule. “Remember, Joey,” he recalls his mother saying, “you’re a Biden. Nobody is better than you. You’re not better than anybody else, but nobody is any better than you.” The Bidens were not impoverished, but they knew failure. His father’s economic trajectory was downward, from Boston suburbs through ventures that went bust, including a crop-dusting business on Long Island. He still wore a suit to work every day. Vanity was an assertion of dignity: dress for the job you should have had, not the one you have stumbled into. An eighth-grade Biden, lowly Catholic attending a school mixer at a Presbyterian church, had to wear one of his father’s oversized dress shirts, the cuff-links made from nuts and bolts.

Politically, the Bidens were Truman Democrats willing to give Ike a chance, but the Biden sensibility reached back to an earlier era, to the local machine politics and ethnic enclaves of the early twentieth century. Their world feels drawn from the novels of James T. Farrell, written in the 1930s and ’40s, set in the working class urban north: rambling portraits of Lonigans, O’Neills, O’Flahertys, and so on, good-hearted but tragic stiffs, drunks, and bigots who love their mothers and wives, and feel guilty about them. Funerals punctuate Farrell’s novels, too.

Biden’s political consciousness was formed, he’d say, at the kitchen table of his Irish Catholic grandfather. Biden was, and in some weird way remains, a boy eager to be included in the conversations of older men. Grandpop would defend the local Democratic machine against the more genteel progressive reformers, because at least the party boss was straight with you. Beware the country club types, grandpop said, especially the ones who “think politics is beneath them,” who “think politics is only for the Poles and Irish and Italians and Jews.” Thinking themselves above it, they’ll sell you out. What the country club might see as corruption was actually the benign and even noble workings of democracy. By that archaic code, what looks like dirt is actually virtue.

From there it is not so long a leap to the politician we know. Biden was the family’s first national politician the way families have a first child to go to college—which for the Bidens is also Biden. He entered the arena as a poor man’s Kennedy, handsome and toothsome. His vocabulary, even now, spans the folksy and the hifalutin. “Malarkey” is a favorite word. There’s a lot of “God’s honest truth” and “my word as a Biden,” alongside fancier law school words like “subrogate.” He has been mocked for misusing “literally,” but I don’t mind it. He uses it for emphasis; what he means is closer to literarily, as in worthy of literature. To overcome his childhood stutter, he memorized paragraphs from Emerson’s “American Scholar” and recited them over and over again, watching his jaw struggle in the mirror: “Meek young men grow up in libraries. ... Meek young men grow up in libraries.” Reciting Emerson in a mirror is Biden’s answer to Abraham Lincoln doing math on a shovel.

In 1966, Biden married Neilia Hunter, a non-Catholic from the better side of the tracks—also the Republican side. He was 29 when he was elected in 1972, upsetting the Republican incumbent in Delaware. He turned 30 in time to meet the Senate’s constitutional age requirement. The New York Times misspelled Neilia’s name (“Nealia”) in the small item about the accident that killed her: Her station wagon was hit by a tractor-trailer. Their one-year-old daughter Naomi also died; sons Beau and Hunter were severely injured but made it through. “I began to understand how despair led people to just cash it in; how suicide wasn’t just an option but a rational option,” Biden wrote in his first political autobiography, in 2007. “But I’d look at Beau and Hunter asleep and wonder what new terrors their own dreams held, and wonder who would explain to my sons my being gone, too.” His chronicle of the ordeal has a simple eloquence: “My future was telescoped into the effort of putting one foot in front of the other.” Biden considered resigning, but agreed to stay on for six months.

Biden’s political personality follows from that sudden tragedy, and from the rhythms of working through grief. Amtrak Joe first started taking the train from Wilmington to Washington and back, every day, in order not to miss a night with his sons. What began as a story of mourning and infrastructure would become the main symbol of Biden’s common touch, even if he takes the Acela. Mr. Smith commutes to Washington.

Since Biden has been around so long, and now seems too old for the presidency, it is striking to recall how young a senator he was in 1973, nary a year older than Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is today. But he was not really a politician of generational change. He was a few years older than the Baby Boomers, whose age cohort would not reach the Senate in significant numbers for another decade. He had married young, received a law school draft deferment, and had his first child by 1969. He embraced the early civil rights movement but did not identify with the New Left. “Biden resents being called the bright young liberal of the New Left,” Kitty Kelley observed in a lively, gossipy profile of him in 1974. He boasted liberal positions on “civil rights and civil liberties,” and on health care, “because I believe it is a birth right of every human being—not just some damn privilege to be meted out to a few people.” But when it came to “abortion, amnesty, and acid,” Kelley quoted him saying, “I’m about as liberal as your grandmother.”

Biden shows Kelley his “favorite picture” of his late wife, in which she’s wearing a bikini. “She had the best body of any woman I ever saw. She looks better than a Playboy bunny, doesn’t she?” Looking back on the long hours of his Senate campaign, Biden says sadly that he would usually get home too tired to talk. “I might satisfy her in bed but I didn’t have much time for anything else.” A year and a half after her death, he is dating a journalist but knows he’s “still in love with his wife.” The hint of prurience was probably less incongruous in the 1970s than it would be now: Biden combined an up-to-date sexual frankness with a more archaic family-man conservatism. He was a cradle Catholic who had embraced birth control.

In 1974, a little over a year into his first term, on a PBS public-debate show about campaign finance reform, he called himself a “token young person,” “like the token black or the token woman.” Small gasps and chuckles could be heard in the audience when he made this comparison. But within the small world of the Senate, at least, he was a token: The average age of the Senate was 55. (It is 62 now, alas.) A token is not part of a wave; to the contrary, Biden had to form alliances with older senators. The only way he secured the positions that later defined his career—leadership of the Senate Judiciary and Foreign Relations Committees—was through strategic deference to his elders. Within the Democratic Party, those elders included lions who had struggled to sustain something like an American welfare state, like Hubert Humphrey, and the old segregationists of the South, like James Eastland and John Stennis.

This micro-generational experience has made Biden an interesting but also frustrating narrator of recent American history. His eulogy for the South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond in 2003 is a case in point. Thurmond, the original Dixiecrat of 1948, famous for a 24-hour filibuster against civil rights in 1957, had defected from the Democratic Party in 1964, as Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act. By the time Biden showed up in the Senate, Thurmond had hired a black staffer, ostensibly turning some kind of page on his racist past. Thurmond and Biden formed an unlikely cross-party, trans-generational friendship. In his eulogy, Biden emphasized that change of heart: “I choose to believe that Strom Thurmond was doing what few do once they pass the age of 50: He was continuing to grow, continuing to change.”

Biden also told a story there that he’s told many times since. In 1990, he took the office of another old segregationist, the retiring Democratic Senator John Stennis of Mississippi. The mahogany table in that room, Stennis told him, “was the flagship of the Confederacy from 1954 to 1968”; the Southern Manifesto had been signed upon it, but “now it’s time,” Stennis said, “it’s time that this table go from the possession of a man against civil rights to a man who is for civil rights.” The story ends with Stennis’s tendentious moral awakening:

“The civil rights movement [Stennis said to Biden] did more to free the white man than the black man.” And I looked at him, I didn’t know what he meant. And he said in only John Stennis fashion, he said, “It freed my soul; it freed my soul.”

It is a great story for a eulogy, and Biden is a fluent eulogist. In the telling, though, the civil rights movement is reduced to an old white man’s tidy moral melodrama. Biden arrives at the melodrama’s conclusion, as if granting absolution after a deathbed conversion. It is not his to grant.

“All politics is local.” It is

an oft-quoted, scolding reminder to D.C.-types that their policies will be

judged against the hard and humdrum facts of their constituents’ lives. Wise

words. Then again, the only people who ever have cause to utter this truism are

the ones whose ambitions are not at all local. The phrase is attributed to Tip

O’Neill, the former speaker of the House in the 1980s and, like every

half-remembered congressman, Biden’s old friend. Biden has claimed “to improve

on that statement”: “I believe all politics is personal, because at bottom,

politics depends on trust, and unless you can establish a personal

relationship, it’s awfully hard to build trust.” This improvement on the

“local” bromide is in fact a very different idea, and not necessarily an

improvement. It asserts not concrete interest but mere personality. (It is

also, while we’re at it, the opposite of the New Left-era feminist refrain that

“the personal is political.”)

Biden applies the maxim, first, to the emphatically non-local arena of foreign policy, because in foreign policy you have to negotiate with “people from different countries” who “know little about one another, and have little shared history and experience.” This was central to his profile in the 1980s and 1990s, as a senator who knew world leaders by name and by handshake, and who cast liberal internationalism as a game of mano-a-mano, eye-to-eye. This has given him an abundance of “personal” anecdotes, like the time he was in Moscow to talk arms control, and said to Soviet premier Alexei Kosygin, “They have an expression where I come from: Don’t bullshit a bullshitter.” Biden’s Kremlin has the same codes as the old Scranton political machine.

All politics is personal is the slogan of a glad-hander, and glad-handing is what Biden does. Domestically, Biden’s appeal smacks of locality, but it is not a rooted locality. The Bidens are relatable because they moved for work. He hails not from Scranton or Wilmington, but from postindustrial Everytown, USA. His spiritual home is less a particular place than the train between places. For that matter, the Delaware he represented in the Senate is the Delaware of banks, rootless corporations that keep Delaware zip codes because of the state’s favorable tax laws. Biden’s support for that “local” industry has made him, as one profile put it, “the Senator from MBNA,” the Wilmington-based bank bought by Bank of America in 2006.

Biden’s glad-handing is not without depth, though. He isn’t exactly a traveling salesman. The glad-hander was one of the central modern personalities in David Riesman’s midcentury portrait of American national character, The Lonely Crowd; beneath the glad-hander’s ingratiating smile, there pulled an undertow of yearning and anomie, symptomatic of the culture that produced him. The Bidenite glad-hander, that is to say, offers emotional connection in a society of strangers, and having known sorrow makes Biden the best glad-hander in the business. He is unctuous, but his unctuousness carries some powerful residue of sacred unction. It is somehow unsurprising to learn that Biden himself received Catholic last rites—extreme unction—in 1988, when a brain aneurysm leaked and he was rushed into surgery. “It surprised me,” he wrote later, “but I had no real fear of dying.” He has had a foot on the other side. I am not saying that Biden has traded on family tragedy; rather, he is fluent in the esoteric language of private grief, and can detect that language’s other speakers. He joins us for a moment in our quiet corner of loss.

What I am describing is not as shallow as someone “feeling your pain,” the way Bill Clinton felt your pain. The contrast with Clinton is instructive. The slightly younger Clinton, a true Boomer, was another “New Democrat” associated in the popular mind with a specific place and with white economic hardship. Clinton was the boy from “a place called Hope,” an Arkansas Bubba, who became a “tactile politician” in the worst sense. But Clinton projects cunning: He made his way to Yale and Oxford, and had a prodigious memory and granular command of policy, which fueled his tendency toward devious ideological triangulation. Clinton’s scandal combined demonic sensuality, abuse of power, and craven dishonesty. Of the Lewinsky affair he said, years later, “I did something for the worst possible reason—just because I could,” sounding like a Baptist preacher who’d been corrupted by power but found salvation.

Biden

does not project cunning, and his sins are, so to speak, venial. Charges of

plagiarism derailed his first run at the presidency in 1987. It emerged that as

a law school student at Syracuse, he had lifted five pages from a law review

article; after an inquiry, he had to retake the class. That he also seemed to

have borrowed a few lines from a British Labour politician for his own stump

speech dogged him as well, and he dropped out in September of that year. In

Biden’s own account of the law school inquiry, he was a disorganized

underachiever at the time, and he’d missed the class where they learned the rules

of citation. True or not is beside the point: A Bidenite plagiarist is a man a

little out of his league but good at heart, who knows he doesn’t have a lot of

time because none of us has a lot of

time. It is both an exculpation and an orientation toward fate.

When Biden was young, he

befriended the old. When he got old, he befriended the young. The personage who

has entered the presidential election is a contradictory figure: a mature young

man who became an immature old man. Nostalgia is the central note of his

presidential campaign, but that nostalgia has many vectors.

First, there is the Biden of the late 20th century. Having emerged as one of the Senate’s foreign policy wise men, he might have been an interesting Democratic president for a post–Cold War world, and in fact voted against the first Gulf War. Biden winning the 1988 election is a potentially interesting counterfactual scenario. The factual history, though, is dismal: He became one more member of the cohort that disgraced itself in enabling the Iraq War and the War on Terror. (His one great distinction, at least, was to be a great talker with an ear for insult—like his line in 2007 that every Rudy Giuliani sentence had three parts: “a noun and a verb and 9/11.”) Biden’s pious laments about “the decline of common decency” in the Senate ring hollow; his cohort wrought suffering on a scale that overwhelms the grammar of grief that is my subject here.

Then there is the reinvented Biden of the vice presidency. In 2008, he added the ballast of elder statesmanship to the Obama campaign, and appealed to the American middle. The fact that he had eulogized Strom Thurmond was not a political liability but an asset. Biden was novel for being the first modern vice president who was significantly older than the president. (Dick Cheney, though vampiric, was only five years older than George W. Bush.) The implications of this age gap for Biden’s own aspirations were not obvious at first, but now, after eight vice presidential years, he is in the curious position of carrying on the legacy of a much younger man, a man who was himself received as generationally transformational. The nostalgia Biden evokes is thus cross-generational: The eminently memeable bromance of Obama and Uncle Joe has been a fixture of the smartphones of young voters who have only really known that era.

Among older liberals, meanwhile, the Obama-Biden friendship has unfortunate overtones of the movie Green Book, in which a working-class white-ethnic type forms a familial bond with his more affluent boss, an extraordinarily talented but rather too aloof black man. A Biden victory in the Democratic primary would be irritatingly consistent with the success of Green Book at the Oscars.

And then there is the figure of “Diamond Joe,” the caricature of Biden in The Onion that has taken on its own weird brilliant life. After a first quick appearance at Obama’s inauguration in January 2009 (“Joe Biden Shows Up To Inauguration With Ponytail”), Diamond Joe’s real debut was in May of that year: “Shirtless Biden Washes Trans Am In White House Driveway.” It’s a white Pontiac from 1981, and the stereo blasts Night Ranger’s “(You Can Still) Rock in America.” Has a satire ever so effectively overwritten the image of a politician? Where the real Biden’s background evoked Studs Lonigan, a Depression-era socialist realism without the socialism, Diamond Joe is a creature wholly of the late 1970s and ’80s. Should Diamond Joe “pony up 200 smackers” for Scorpions tickets? “This,” he says, “is the toughest decision I’ve faced.”

The full corpus of Diamond Joe amounts to a powerful and paradoxical new origin story. It is intriguing that this fantasy caricature of Biden makes him an endearing outlaw, when the real Biden’s political legacy includes the 1994 Crime Bill, and the terrible scale of mass incarceration that followed from it. Diamond Joe sells drugs and does drugs (“Biden Frantically Hitting Up Cabinet Members For Clean Piss”), and leaves felonies off of job applications. The caricature lets its subject lovingly off the hook: Diamond Joe chafes against the laws that the real Biden pushed through Congress.

Sometimes he is an ever-more-juvenile septuagenarian. “Biden Donates Collection of Classic Skin Mags to Those in Need During Holidays”: a single headline threads Biden’s sexual frankness, his nostalgia, and his sentimental connection to the down-and-out. Diamond Joe evinces jubilant sleaze without sexual predation. The people’s taboo-breaker extols masturbation without shame and with generosity. At other times, Diamond Joe is wistful and wizened. “I have been treated as a punch line,” he says in a 2012 vice presidential debate. “A dope. A fuckin’ jester among kings. But don’t be fooled. I am also a man who has touched sorrow.” A keen comic mordancy seeps inexorably into the ballad of Diamond Joe: “Nude Biden Wakes Up On Cold Slab In D.C. Morgue,” read a headline in 2013. “Not again,” he says. “Diamond Joe’s not going to the boneyard without a fight.”

Where the real Biden’s career in the Senate began with sudden family tragedy, his vice presidency closed with a slower one. His oldest son, Beau, followed his father into politics and became attorney general of Delaware in 2007. In 2013, he was diagnosed with brain cancer, a Stage IV glioblastoma. After radiation, chemotherapy, and a more experimental treatment, he died in May 2015. Biden was again at the center of national sympathy, no longer a young widower but a grieving father. The outpouring was even more immense now; Beau’s funeral fell somewhere between a state funeral and a private family funeral to which all Americans were invited. It felt strangely like mourning a political dynasty that might have been. Obama delivered a eulogy. The most poignant of Biden’s generational inversions is to be a father carrying on the legacy of his late son.

Biden’s second memoir—Promise Me, Dad: A Year of Hope, Hardship, and Purpose—appeared in 2017. It is a complex book, partly a political memoir and partly a grief memoir. The political memoir bolsters Biden’s image as ready manager of foreign relations. To Biden falls the major dramas of Obama’s foreign policy: “Joe will do Iraq,” Obama says. “He knows it. He knows the players.” The unlikely marriage of genres is often affecting. The official residence of the vice president, for instance, is the Naval Observatory, which houses the U.S. Naval Observatory Master Clock, which calibrates the nation’s Precise Time. “Synchronized to the millisecond,” Biden writes, Precise Time “had been deemed an operational imperative by the Department of Defense, which had troops and bases in locations around the globe.” The official time of the national security state, “ticking away in metronomic perfection,” thus tracks the melancholy counting down toward a death in the family.

But the marriage of genres is also unsettling. Most remarkable is the book’s explicit and detailed intertwining of Beau’s treatment with the Obama administration’s first actions against the Islamic State in Iraq. The effect is curious, for it is not clear whether war is the allegory for Beau’s treatment or Beau’s treatment is the allegory for war. Beau underwent an experimental virotherapy in late March 2015, the same week the U.S. launched airstrikes on the long-suffering city of Tikrit, a site of civil war and sectarian strife in the wake of U.S. invasion. The virus (a “viral smart bomb,” Biden calls it) is supposed to mobilize Beau’s immune system against the tumor; the airstrikes are supposed to unify and boost Iraq’s various factions against ISIS. The procedure succeeded in Tikrit, but ISIS conquered Ramadi in mid-May; Beau died May 30. The doctors’ uncertainty—they “couldn’t be sure if it was the virus at work or the tumor”—resembles the confusion of American foreign policy.

The book offers Beau’s death as a sacrifice that might redeem the misbegotten war in Iraq, for which Biden voted in 2002, and in which Beau served from 2008 to 2009, as a member of the Delaware National Army Guard: “He always insisted that what the United States was trying to do was noble,” Biden writes. “If there was a reasonable chance to get it right in Iraq—for the long term—Beau believed we should try. We had sacrificed too many good people already to give up.” It is a powerful gesture, but unsatisfying. The book’s narrative cannot furnish a happy ending, only a double loss. (The Iraqi recapture of Ramadi, some six months later, is mentioned in the epilogue; a more robust anti-ISIS strategy emerged only after the book’s main events.)

In October 2015, Biden announced he would not run for president, but in the same speech channeled his political energies toward a cancer moonshot, framed in centrist terms: “I know there are Democrats and Republicans on the Hill who share our passion—our passion to silence this deadly disease.” In 2016, Obama announced more federal funding for cancer research and collaboration; in his final State of the Union address, he said he was “putting Joe in charge of Mission Control,” because Joe had “gone to the mat for all of us.” This, had he rested there, would have been a fitting and conclusive extension of Biden’s maxim that all politics is personal: Cancer became the next region he would handle.

Step back from Biden’s

forty-some years in national politics. Is there an ideological thread? A

unified theory of Bidenite politics? Not really. One does not look to him for

ideological robustness or even coherence. He is not “divisive,” exactly; it’s

just that his long time in public life leads different people to see different

Joe Bidens: precocious young senator or bumbling old senator, tribune of the “white

working class” or tribune of Delaware-based banks, champion of battered women

or clumsy misogynist, friend of cops or outlaw Diamond Joe. He has registered

rather than transcended the major tensions of his time.

Yet on another level it is possible to articulate what for Biden is the elemental atom of political interaction: It is the communion of strangers on a train, who happen to pour their griefs out to one another because, after all, it’s easier with someone you don’t really know. Such an atom yields no grand vision of politics, and hardly meets our moment. But it still vibrates on a poignantly American frequency. Biden is the politician of fleeting but profound intimacy.

Consider one remarkable detail from his memoir. He gave a eulogy at the funeral of one of the two police officers killed in New York City in 2014; the remarkable thing is not the eulogy itself but what he tells one of the widows privately. Right now everyone is there for you, he says, but eventually they’ll go back to normal, and then grief will get harder: “After a while you’re going to start to feel guilty because you’re going to be going to the same people constantly for help, or just to talk.” So he gives her his private number: “When you’re down and you feel guilty for burdening your family and friends, pick up the phone and call me.” The reader glimpses a secret society of grievers:

I have a long list of strangers who have my private number, and an invitation to call, and many of them do. “Just call me when you want to talk,” I told her. “Sometimes it’s easier to pour your heart out to somebody you don’t know well, but you know they know. You know they’ve been through it. Just pick up the phone and call me.”

It is hard to imagine reaching for the phone to call, in a dark and lonely hour, the sitting vice president of the United States. And yet I hope this strange, beautiful story is true.

Ours is not a culture comfortable with death. According to Philippe Ariès’s The Hour of Our Death, a monumental thousand-year history of Western attitudes toward dying, life’s inevitable conclusion was, in the deeper past, “tame,” its meaning known, its ceremonies familiar. Over the centuries death was untamed, individualized, romanticized, desperately and neurotically denied. Modernity made death a taboo: An ambient anxiety about death looms, yet we banish it from consciousness. Medicalization, furthermore, moved death from the home to the hospital. These glacial shifts remade mourning, too. In the deeper past, mourning had a genuinely communal, public function. “Mourning,” Ariès writes, “expressed the anguish of a community that had been visited by death, contaminated by its presence, weakened by the loss of one of its members.” In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, mourning was privatized: confined to the family, to the home and the “funeral home” (a modern industry).

The medicalization of grief, as a psychological condition, tracked the medicalization of death. In the 1960s, the British anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer took stock of modern mourning, after finding that his own persistent grief over his dead brother had produced a strange social awkwardness. He concluded that grieving was now treated “with much the same prudery as the sexual impulses were a century ago. ... Today it would seem to be believed, quite sincerely, that sensible, rational men and women can keep their mourning under complete control by strength of will and character, so that it need be given no public expression, and indulged, if at all, in private, as furtively as if it were an analogue to masturbation.” Ariès put it this way: “The bereaved is crushed between the weight of his grief and the weight of the social prohibition.”

Our now-conventional therapeutic vocabularies of grief began as rebellions against that mid-century prohibition. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s On Death and Dying appeared in 1969. What she identified as the stages of a terminally ill person’s confrontation with death—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance—were soon doubled into the bereaved person’s “stages of grief.” What was a rebellion—to describe directly the thing from which we had learned to look away—became, over time, less descriptive than prescriptive. The stages of grief seeped so fully into the culture that it became a kind of recipe. And grief remained a malady to be gotten over.

Biden often speaks the conventional surface language. In October 2015, he cited the “grieving process” in his decision not to run for president. “I know from previous experience that there’s no timetable for this process,” he said. “The process doesn’t respect or much care about things like filing deadlines or debates and primaries and caucuses.” Process: standardized yet not communal, internal yet foreign to our selfhoods, as if grief were a paramecium. The same day, The Washington Post ran a news item: “Joe Biden made the right decision not to run for president, grief experts say.”

In the ’70s, Biden worked through grief—needed to work through grief. This was soon after the publication of Kübler-Ross’s On Death and Dying, but before the “stages of grief” had really congealed. He now spans the pre-Kübler-Ross and post-Kübler-Ross discourses. When grief was, as Gorer found, a thing to be mastered in public, some would succeed in mastering it and others wouldn’t. Biden, paradoxically, talks and writes publicly about not wanting to give vent to private grief, based on the old idea that such expression would be unseemly, but at the same time he does express it, and does so eloquently, moving in and out of the therapeutic vocabulary. He is grief’s charismatic confessor, tuned to that select constituency of grievers.

There are many reasons not to want Biden to run for president; grief, understood as some psychological enfeeblement, should not have been one of them. Our overblown cult of the presidency makes us imagine that the president has to be a political athlete in top mental and emotional condition, a “Commander in Chief” who fields 3 a.m. phone calls and keeps us safe. This already idiotic byproduct of the imperial presidency and the national security state became steroidically idiotic after September 11, 2001. Obama, alas, fed it rather than deflated it. Biden did, too, and thus ironically laid a trap for his own presidential ambitions. The most absurd moment in Promise Me, Dad is a private conversation with Obama: “The country can never be more hopeful than its president,” Biden tells Obama. “Don’t make me ‘Hope.’ You gotta go out there and be ‘Hope.’” The premise is nonsensical: Why would the country never be more hopeful than its president? But more to the point, be hope is so manifestly opposed to Biden’s own real resonance in American culture. He has embodied not hope, but grief.

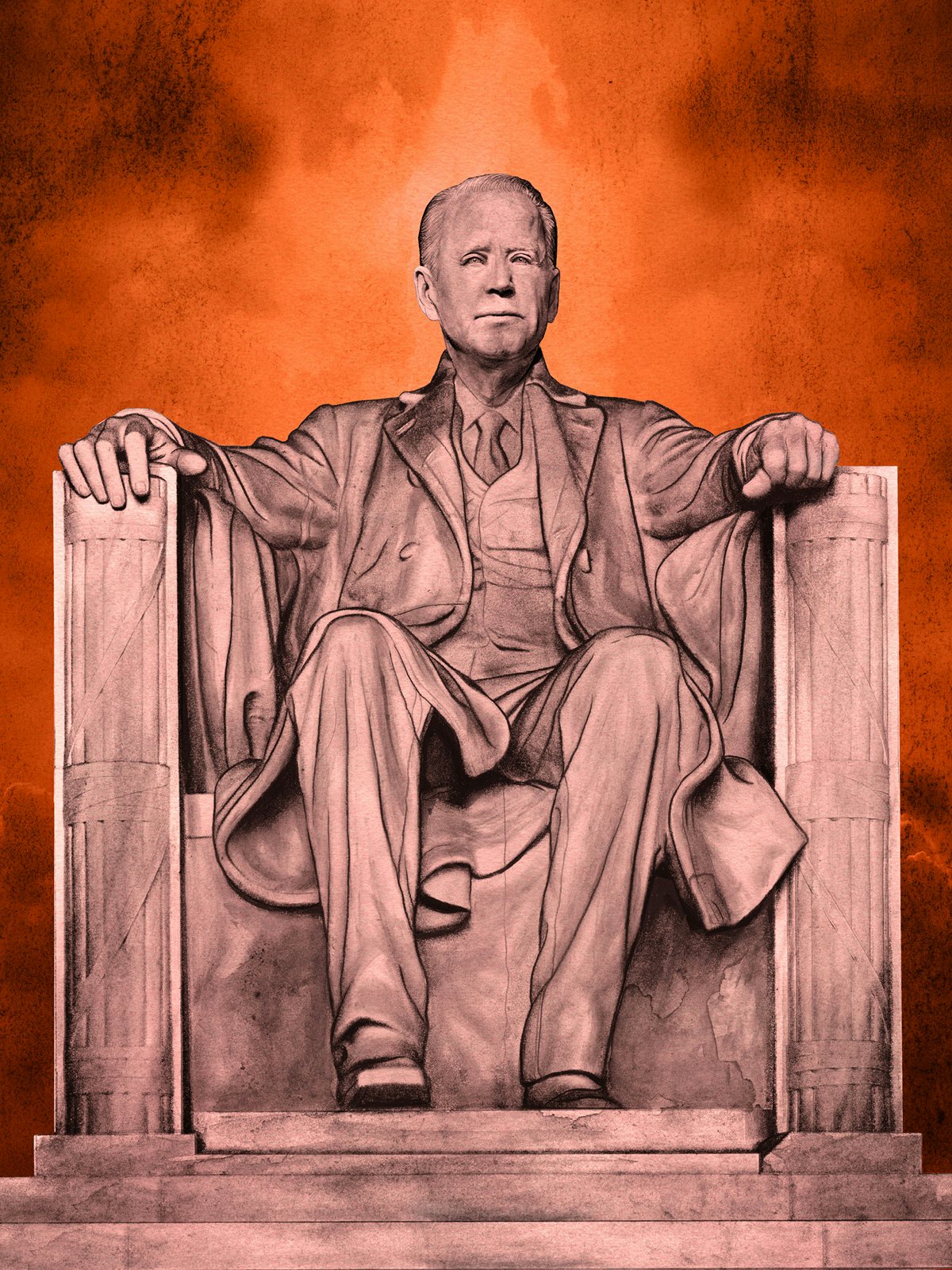

Or, to put it more precisely, it has been Biden’s fate to embody the contradictions of modern grief. Promise Me, Dad bears some harmonies with a novel published in the same year, another intimate study of fatherly grief: George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo, which centers on President Lincoln grieving his dead son in 1862. That novel conjures a strange supernatural language in order to capture Lincoln’s taboo-breaking act of going to the cemetery to cradle his son’s corpse. Biden, beneath the surface language of the “grieving process,” also breaks the taboo. His 3 a.m. phone calls come from grieving strangers. It is oddly poetic, in light of the scandal over Biden’s handsiness, that these encounters smack of “Strangers in the Night,” but with condolence in place of carnality. I am not suggesting that he offers a solution to our squeamishness, for it has no solution, only that his funereal entrance into and exit from national politics made him the rare politician to cross the line between public and private mourning.

The signal irony of Biden’s career is that while he has long sought the presidency, grief has best fitted him to the vice presidency, a job traditionally scorned by other ambitious men. Gerald Ford’s vice president, Nelson Rockefeller, was asked what he did in the job: “I go to funerals,” he complained, “I go to earthquakes.” But Biden, American threnodist, filled that empty position with more meaning than the Constitution’s authors could ever have imagined: It proved to be the ideal avenue for his full emergence as our itinerant mourner. He made mourning not a malady but an art.

“I grieve that grief can teach me nothing.” The sentence is Emerson’s, from “Experience,” an essay written in 1844, two years after his own son’s death. How cold it seems, at least at first, as if the primary grief is canceled mathematically out by the secondary grief: Grief has no utility, let us dispense with it. A terrible thought. But this is a misreading, for that secondary grief about grief’s failure is, after all, still its own kind of grief. This is also terrible, but not cold. One feels in it a quiet, spiraling sorrow.

Biden, Emersonian recitations in his childhood mirror notwithstanding, is the un-Emerson: Grief has been central to his education. It has taught him a manner of communion, something like a pre-political or supra-political language. It is esoteric but crosses political divides. What that grief should teach us, as a polity, is harder to say. Biden’s 2020 campaign marshals grief anew, in a manner distinct from the secret, salutary mourning he performed as vice president. Sad ironies abound in this. Grief—unmastered, unprocessed—kept him from running in 2016, though he may very well have won. But now, grief has been refined into purpose (we might call it Biden’s sixth stage of grief) and propels him toward the presidency again.

We should not underestimate the force of this appeal, drawing as it does on another kind of grief. Biden 2020 lowers a bucket into the broad and deep well of liberal grief dug by the 2016 election and by the disasters it has wrought. Polls are ill-equipped to isolate such collective grief and its electoral implications, especially when coiled with nostalgia. It is fitting that Biden placed the 2017 Charlottesville attacks at the center of his announcement, and more fitting that he made a personal call to the mother of the woman who was killed that day: He would forge a spiritual link between the bereaved, and between Heather Heyer and his own son, and thus bring one grief-borne purpose together with another.

Purpose is not the same thing as wisdom, though grief can yield both. Biden’s appeal is therapeutic rather than structural; it is less a “message” than a psychological drama. That he has superimposed private grief onto our political moment is powerful. But it is still a superimposition and possibly a category error, though made in good faith. Biden is surely not alone in that error. Trump’s election inspired endless applications of Kübler-Ross’s stages to national politics, in earnest or in jest. Those stages are, I fear, an even less adequate recipe for political action than they are for grief itself. It would be a cruel irony that the politician most identified with the “grieving process” would now launch a presidential campaign that is stuck somewhere in the stages of denial, anger, or bargaining.

I want to close this melancholy essay not with callous prognostication but with my own small salute to itinerant mourners. It involves funerals and a ribald pun. I was 22 when my father died, years ago. My own grief did not fit the stages, and it defied “process.” Surely I did it wrong. Anyhow, an old friend of my father’s showed up to the funeral, a man I had never met and whose name I do not remember. This old friend was not a local guy—my father grew up in Brooklyn but the family had moved to Wisconsin, and I’m pretty sure they had long fallen out of touch. I have no idea how he knew my father had died. What I do remember is him telling me a story about them in Brooklyn, probably in the mid-1960s, when they were themselves 20 or so. One day they arrived at my father’s family’s apartment just as his mother, my grandmother, was leaving the house. She was on her way to a funeral. It was a social obligation rather than the funeral of someone close, but for some reason she was totally decked out, as the stranger told it—all black and even wearing a veil. “Georgie,” she asks my father, “do I look sufficiently funereal?” My dad’s response: “Mom, you look like you’ve got a funereal disease.” It was the right story and I was grateful.