Almost exactly 56 years ago, Gloria Steinem published an investigative tell-all in Show magazine titled “A Bunny’s Tale.” She had applied for a job as a Playboy Bunny under the name Marie Catherine Ochs, chosen because it was “too square to be phony.” Whether it was the name that did it, or the fact that Gloria Steinem was hot as hell, she breezed through her job interview. Bunny Marie discovered the working conditions to be tedious, uncomfortable, insulting, and at times dangerous. Steinem’s article later went into her essay collection, Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions (1983), which sold half a million copies and canonized “A Bunny’s Tale” as a historic event—the day a Bunny spoke back.

I’m no Bunny. But there’s a lot of good advice in “A Bunny’s Tale” about how to conduct an investigation. When I learned late last year that the Playboy Club was reopening (the original New York outpost closed in 1986), it seemed a delicious opportunity to assess, by way of juxtaposition, the world we live in now. Playboy founder Hugh Hefner died in 2017—may he rest in a heaven of baby oil and Viagra—and the version of femininity he espoused to such success (body meeting certain specifications, character docile) has taken a tumble down the stock market of cultural capital. The Playmate was this strange man’s invention, a girl, he said, with “no lace, no underwear, she is naked, well-washed with soap and water, and she is happy.”

Playboy still merchandises its iconic rabbit logo to clothing companies and other branding outlets, but the larger Playboy culture machine has ground to a halt. The mansion in Los Angeles has been sold off; the bunnies’ leporine reign is over. The company has switched direction, and the revamped print magazine—a thick, glossy dossier with tasteful nudity, an inclusive ethos, and no advertising—is no longer Playboy Enterprise’s best-known product.

Meanwhile, Hefner’s throne is empty, and nobody wants to fill it the way he did. We are living in a slightly different world from the one that #MeToo intervened in the year before last. Now that scandal has culled so many patriarchs from their corporate dictatorships, only a fool would pitch his career on being a brand’s louche daddy. But what happens in the world of PR never quite aligns with the world of lived experience, and the disintegration of the Playboy brand isn’t the same thing as real change in the way that people act on their desires. Gazing at a press release for a Playboy Club event in New York, I wondered how it might be possible to lift a magnifying glass at that place in culture—the gap between what seems to be happening to gender norms according to the media, and what is actually occurring in private, sexualized, straight spaces.

And that’s how I found myself clop-clopping down 42nd Street in ill-fitting shoes and clip-in hair extensions, gathering the mettle to approach the velvet rope.

Like Steinem, I planned to go

undercover. Like Steinem, I aimed to record my subjective experience of the Club;

to undergo some discomfort; and to identify the tiny, rich moments that

define the experience of being a man or a woman or whatever you might be. One

of Steinem’s sentences in particular was etched in my mind: “Three women in

mink stoles stood waiting for their husbands, and I could see them staring, not

with envy but coldly, as if measuring themselves against the Swiss Bunny and

me.”

I could see them staring. As I sat at the M.A.C. counter having a full face of makeup applied for my fledgling reporting mission, Steinem’s line about reflected gazes seemed to zip around the room, from mirror to mirror. The Playboy Club had my real name and occupation, but I did not want to show up as myself; I’m nonbinary, my gender presentation ordinarily something like hard femme teenage boy. I intended to disguise myself that night in a mask of high feminity—to go full glam. There are many ways to be undercover, after all; many of us do it everyday.

If you ever want to see joy ripple through a cosmetics store, I recommend requesting a disguise. In this temple to beauty, its priest-artists transformed my face into something barely recognizable. The makeup went on slowly, in layers. Under my eyes it became incredibly thick. I had not previously noticed the wrinkles there. They’re like tiny canyons. Up close they must resemble a deep and craggy topography, now filling up, flash flood-style, with beige goo.

Next, I visited a beauty supply store that sold hair. A pitying salesperson managed to deduce what I needed, and a colleague back at the office executed the installation. The final effect was astonishing: a cross between a fetching news anchor and a pretty Instagram influencer. I was humbled by the change that this face and hair had wreaked on me, the intensity of how I felt. I kept my sunglasses on when I walked out on to the street, afraid of unleashing whatever unknown power my new face might have on my surroundings.

My dress was long-sleeved and navy blue, an anxious Uniqlo purchase never previously worn. I had not thought to buy a handbag, so I hastily decanted the contents of my backpack into a free publisher’s tote that was, at least, new. I took a taxi from The New Republic’s office in Union Square to the Club, which meant that I had a total of about one minute’s practice in moving through the world in my disguise, and a long car ride to wonder what on earth I was actually doing, what kind of article I was beginning. Getting in the taxi at all was a challenge. I would usually put one leg in and then drag my body after it, but this time I attempted what I have seen well-bred English ladies do, and entered ass-first before pivoting in my pressed-together legs.

My teeth were chattering slightly from nerves when I arrived at the Playboy Club for what was billed as a “Verbal Burlesque, an Evening of Spoken Word & Music.” The press release promised “the dynamic spoken word histrionics of Lydia Lunch,” and a reading by Michael Imperioli from his debut novel. (You may know Imperioli from his role on The Sopranos as Christopher.) Already, here was something different: a nod to the cabaret history of the Club, which used to host comedians, but muddled with a downtown artistry that seemed aspirational, intelligent.

Still, I was afraid, and mostly of the women. Denizens of the Playboy Club would see that I was an intruder, I was sure, and for some reason I was worried they would feel insulted by my subpar efforts, like sommeliers offended by an affected order of pinot noir. In my notes, I wrote down “failing at the project of being a woman.”

The Playboy Club has a black awning, over a tiled patio-style entrance that includes a couple of steps, a witty doorman, and a long snake of red velvet rope which that doorman unclips and then re-clips between each guest. Past the front door, a dark shiny corridor leads toward the coatcheck. You must then turn left, where the hostess station greets you.

The station was in some chaos. There were four Bunnies behind a lectern, and they seemed to be trying to speak both with each other and the many guests gathered in line. The sense of disorder was heightened by the shock of seeing so many women dressed in corsets. They were all stunningly gorgeous, and tall; they all smiled. It was like being hit with a wall of charm and legs. The classic Playboy corset remains unchanged, although it was technically redesigned in 2005 by Roberto Cavalli, who also lengthened the bunny ears. The tails sit oddly low on the bum—I had expected them to perch on the Bunnies’ buttocks like a birthday candle.

Of course I fell in love with one of the hostess Bunnies instantly. For whatever mysterious reason, I presumed her to be only inadvertently wearing a rabbit costume while pursuing a larger journey. She had extremely large and expressive eyes. Having announced I was on a press list, I walked past the bar into a multileveled space clad in red brocade wallpaper. Everything that wasn’t red was black, or mirror, or flecks of vintage Playboy magazine photographs decorating the walls. The lights were low, and people were moving around.

It was not clear where the performances would take place, and I was not there to have dinner alone, so I had no idea where to go or where to sit. A small lounge area was full of customers aged around 45, all of whom refused my requests to “squeeze in” beside them. Paralyzed, I stood in the middle of the room and wrote, “The seating. No seats left for the event: it’s impossible to keep track of who is and isn’t in charge of you because they all look like fucking Bunnies.” The circumstances were conspiring to overlook my existence, but I was so completely distracted by my costume and their costumes that I mistook my conundrum for a kind of malicious underestimation on the part of everyone around me. I caught a barback and asked if there were any spare seats, since I was there to write about the performance. “Oh, so you’re saying we should be nice to you in case you write bad things about the place?” he said.

“I suppose so, yes,” I replied. I had forgotten that I was here to observe other people and their interactions with me, not blackmail staff members into giving me special treatment.

“Okay, I’ll see what I can do,” the barback said, and laughed.

I found a spot on an elevated level of the room, which had a banister over which I could watch the performance. My new friend brought me a chair. Lydia Lunch came on, wrapped in her aura of anti-establishment confidence, ready to deliver some spoken word work to a grinding musical accompaniment. She was not satisfied with the sound. She and her co-performers kept barking requests to raise the volume of the mic, demands that were not met. Eventually Lunch lost her temper with the people sitting a few feet away at dining tables, chastising them for making too much noise while eating their dinner. “This is what happens when you spend all the money on the decoration and none on the sound,” she declared.

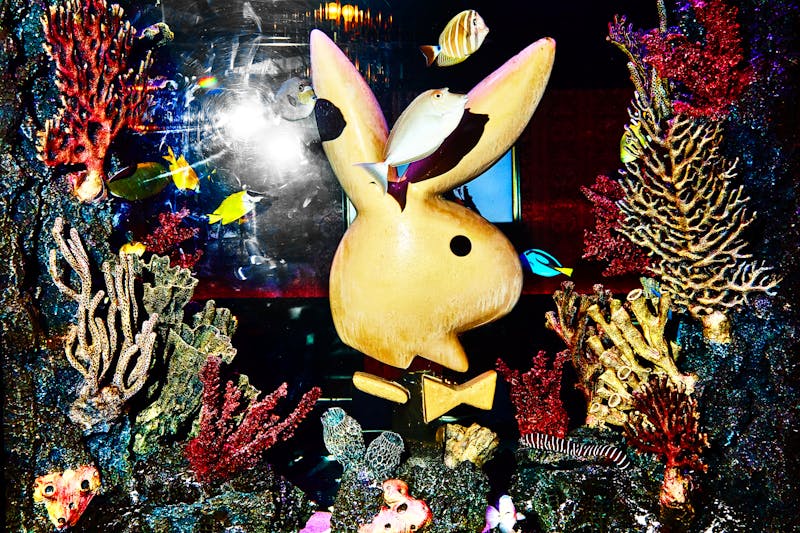

The décor was all right, but it didn’t look like it was worth all that much. In the middle of the dining section sits an aquarium, full of beautiful fish and a large, three-dimensional model of the Playboy bunny logo submerged inside. There were a few hip young people, but most of the crowd must have been friends or fans of either Lydia Lunch or Michael Imperioli. There were also members of the press. I spied one friend of mine, perhaps drawn by the extreme curiousness of the advertised lineup, but to my satisfaction she did not recognize me. Imperioli’s novel is called The Perfume Burned His Eyes, and it seemed to be about a child who delivers food to Lou Reed and then becomes involved in some kind of relationship with him. Imperioli wore a nice pale suit and glasses, and he has a very elegant swirl of thick grey hair these days.

All these observations I recorded while radiating tension. Strange things were happening. Whenever I looked up from my notebook, I would find a man looking at me, both of us caught in the slightly shameful act of one-way observation. To my panic about being overlooked, then, was added the contradictory stress of being watched. The lesson felt crucial. I left the Club, got into a rideshare taxi. I looked up and was astonished to see the very Playboy Bunny I had fallen in love with step into the car.

“Excuse me, but don’t you work in the club?” I asked her. She did. I said I was a journalist, and that I was wondering if she’d like to speak to me about working there. She smiled a smile that emitted accommodating, professional beauty, but said that she couldn’t. The Bunnies have reps to handle those inquiries, she said. Rebuffed, I waited until she got out of the car to hand her my card, with my cell number and the words “In case you want to talk” written on it in the pen that I had managed to hide in the sleeve of my dress.

“A Bunny’s Tale” came early in

Steinem’s career, when she was in her twenties, several years graduated from

Smith and flitting between freelance assignments. It opens with a description

of an employment ad promising a luxe $200-$300 per week for girls who live the

high life as Playboy Bunnies at the New York Club on East 59th and Madison.

Skeptical of these high rates, Steinem dreams up Marie, writes her a backstory,

and applies for the job.

Steinem delivers several scoops. At the lower end of the list of concerns, all Bunnies wear extremely uncomfortable suits, which they have to pay to maintain and are padded in the “bust” with dry-cleaning bags and other detritus. Bunnies also have to pay out of pocket for their own shoes, which furthermore have to be dyed to match their corsets (Steinem’s are bright orange and bright blue). More disturbingly, prospective Bunnies are sent for medical tests, including STI testing and genital exams. Steinem refuses the exam, preserving her vaginal sanctity like a saint of old, demanding of the doctor, “Is that required of waitresses in New York State?” Steinem’s colleagues tell her that bunnies are not allowed to turn down invitations to socialize from a “Number One Key,” the highest tier of Playboy Club member.

A college-educated woman, Steinem conveys an air of scientific curiosity in, disdain for, and political sympathy with her Bunny colleagues. About one woman whose baby-girl voice jars with her appearance, Steinem remarks that she’s a “big girl and looked a little tough.” As Steinem walks home, she notes that an “available” woman of the night is “more honest” than she, the journalist-Bunny, neatly tying in American culture’s condescending obsession with hookers with hearts of gold. In one excruciatingly novelistic moment, she describes a couple of friendly, nameless black men (she uses the word Negroes) who “looked sympathetic.” They are garbage men, they say. “It don’t sound so good, I know, but it’s easier than your job,” they say.

“A Bunny’s Tale” gives a vivid sense of what the job was like. The Club’s patrons treat the Bunnies greedily, even violently—one girl describes joking to a customer that her tail is made of asbestos, causing him to attempt to light it on fire. Steinem one-handedly carries trays bearing enormous quantities of roast beef. The article is a perfect use of the undercover form. Really good undercover operations require a tension to vibrate between the journalist—or informer, or undercover agent—and the context with which they are trying to blend.

Still, Steinem disguises little

about herself except her name and her job, and she pulls it off quite easily. She

skips lightly through the most frightening part, in my opinion, namely the mute

study of her body during the interview by an unfamiliar woman behind a desk.

She’s here to interrogate broken wage promises and grotesque Playboy punters,

not to waste time experiencing her own femininity. It’s a shame—I’d love to see Gloria

Steinem try to put her own beauty into words.

On my next trip to the Club, I went as my ordinary nonbinary self, just a bit more smartly turned out. With my hair pushed back, a black outfit, and glasses, I looked something like a minor late-1970s Austrian film director. To complete my study of the Playboy Club, a friend of mine, whom I’ll call James, agreed to go as a customer identified as male, and report his observations to me. That way, the spectrum of gender reports would be, according to my contrived rubric, roughly complete.

It was with a sense of strange assurance that I strode once again into the Playboy Club, as if I were on home turf. As our group approached the hostess station, I locked eyes with the Bunny I had spoken to in the taxi the week previously. She seemed to recognize me, before I realized that hostesses must greet all guests as if each of them were a friend.

From the moment James stepped in the Club, he told me, he felt that something was expected of him as a man, though what was unclear. It felt like a strange faux pas on his part, for example, that he let a woman of our company take the lead in speaking to the hostesses. It was also totally unclear how a male guest ought to interact with the Bunnies. Being served by Bunnies felt like a prepubescent boy’s idea of what a male fantasy would be—which you could also call a bent-out-of-shape business model.

Dinner was nevertheless very enjoyable. We ordered food and drinks and held conversations. I sat back in my red velvet chair, luxuriating in being able to control my body in the way that I was used to. Being here again, as myself, felt almost redemptive. The chairs seemed designed for a man to lounge upon in a louche sort of way, with one’s elbows propped up against the long, low back. The place filled up a little as the night went on, with young and attractive people, including, to my surprise, at least one queer date (they got anniversary candles from the Bunnies).

James may have felt alienated, but I felt a heady and vertiginous freedom, as if I were passing through the mirror image of the club I had visited the week before. My old fear now seemed so funny. The gender performances around me lapsed into a series of nonsensical games. Restaurants are full of gendered rituals that generate awkwardness; we have all this choreography about who orders the drinks, what the waitress and you might talk about, who gets the check, and so on. When it’s unclear who is dominant in a group, the system breaks down a little, and I enjoyed watching this broken machine sputter.

All of the staff I interacted with were interesting people. There were some women with truly excellent catsuits—whether punters or staffers, I could not discern—and the Bunnies were extremely charismatic. At any given moment, it was impossible to tell who was doing what, exactly, as the patrons and Bunnies became harder to distinguish. The room became a pleasant blur, like being a guest in that prepubescent boy’s dream. The Club is a muddled place, and in its dimly-lit bathroom mirrors everybody looks a little Mephistophelian. It can be fun to play in the wreckage of the playboys’ world.

The next day, James texted me with a bombshell. The Playboy Club had fired half its Bunnies, according to Page Six. A source also told the paper that, “Service has been so bad that new management had to be brought in.” The source claimed that staff had been hired based on their looks, rather than for their expertise in service. Their duties had been slashed to running drinks only, the source said, and hourly pay rates cut from $40 to $25.

Playboy told me that only three women were let go, not half the staff, while they hired a further twenty Bunnies. The company was less clear about the pay cuts: food and beverage servers, bottle service servers, and hosts all make different salaries, a spokesman said, but did not clarify their dollar amounts. He called the Page Six story an over-reaction to a “minor staffing change.”

Still, uneven management would explain so much, particularly the vague sense that the large-eyed Bunny—my Bunny—was experiencing a different reality below the golden surface of the evening. Steinem’s mission in “A Bunny’s Tale” now seemed far more useful than my own, and more pertinent to the actual situation at the Playboy Club today. Firing instead of retraining your employees sends the message that they are disposable and interchangeable. The problems with the Playboy Club then and now are the same: The Bunnies’ working conditions lag behind the glitzy image projected by the brand.

Labor is an often unseen part of the treacherous gender terrain we navigate. Becoming a Playboy Bunny seems to mean signing up to being treated like yet another undervalued waitress. Certain kinds of women’s labor remain difficult to improve: Those whose bodies traditionally decorate spaces or who work for the enjoyment of men tend to do unpredictable contract-based labor, or rely on tips for income. Although certain parts of patriarchy’s apparatus have rusted out, no longer governing the Playboy Club’s social timbre, the cultural machinery that turns all sex work–adjacent labor into somebody else’s profit is in rude health.

When Steinem became a Bunny, she went undercover in a different way than I did. She shed her name and her biography, keeping her body and face and intelligence. This allowed her to pass as a certain kind of worker. Because Steinem’s politics incorporated bodies and hair and reproductive rights and labor rights under the same feminist umbrella, she was able to move back and forth between the more privileged sphere of culture commentary and the “real” world of men and women. She could be of the world and outside of it; scientist and subject; a victim and the beneficiary of a prestige system that gave educated, white feminist writers of the 1960s the tools to speak the language of their abusers.

Gloria Steinem did not, however, have the tools to speak the language of her colleagues. “A Bunny’s Tale” was meant to be a lighthearted, edgy bit of journalism, but the nuances of Steinem’s identity (Smith B.A., beautiful body, hungry young writer) overwhelmingly informed her interpretations of the people around her, down to the level of their relative importance to her investigation. She’s ostensibly hunting for justice, but keeps getting snared in her own traps.

She is not alone there. Take the Bunny beloved, for example. By working at the Club, she opened herself up to be seen; as a punter, I was adopting a designated role in the club’s economy to fixate, to desire, and ultimately to incorporate her into my narrative of experience. But in my story, she is just a pair of eyes, a Bunny costume. I didn’t write it that way on purpose; it’s just that when I read my own notes, I saw what I had done—reduce, simplify, diminish.

I have repeated Steinem’s gestures in a way both conscientious and messy, and her story still sticks with me like a misunderstood lesson. Like Steinem, I wanted to be of the world and outside it. I wanted to explore the gap between this world and its representations. I have learned that this kind of switching leads to occasional panic, delusion, and other obfuscations of the critical faculties. Just as Steinem declined to put her own beauty into words, I struggled to find language commensurate to the complexity of my gendered experience. As my trophies, I have small moments, like koans. Catching the man looking at me catching the eye of a Bunny. The shimmer in the dark mirror, where a wall of plastered Playmates hover around my reflection like saints. Being seen, half-seen, unseen—then disappearing altogether.