There are writers who specialize in variety, flitting from genre to genre and reinventing themselves with every book. Then there are those who worry the same subject over and over again, as if every novel, every story, is but a facet of a single, monumental concern. Aleksandar Hemon is the latter kind of writer, and his obsession is exile—a theme both as old as The Odyssey and as pressing as the migrant caravans wending their way northward to the United States. For Hemon, exile is more than mere circumstance; it is the fundamental human condition, produced by the irrevocable loss not only of the places where we used to live, but also of the people we used to be. Exile from an Edenic past sets the stage for adulthood, the process of becoming—no, creating—ourselves.

Hemon reinvented himself once already, when as a young man he was cast on America’s shores. In 1992, the then–28-year-old writer was visiting Chicago when the Bosnian War broke out, wreaking destruction in his country and stranding him in what would become his adopted home. Helpless and wracked with survivor’s guilt, he watched from afar as Serbian forces encircled his beloved Sarajevo and besieged it over four sniper-tormented years. Whether Hemon’s escape was a stroke of luck or a tragic turning point is one of the questions that haunt the various alter egos who proliferate in his short stories and novels, caught between a bewildering life they never wanted and the pall of mass death that hangs over their city.

Hemon in real life worked a variety of odd jobs—ESL teacher, Greenpeace canvasser, sandwich maker, all occupations that feature in his fiction, too—before mastering English and becoming a famous novelist. Along the way, he drew comparisons to Nabokov and Conrad, two Eastern European predecessors who also started writing in English later in life, imbued it with foreign vigor, and ran rings around the native speakers. Like the “noble, worldly misfit” in his 2009 story “American Commando,” “who found his salvation in writing,” Hemon believed in art’s regenerative power. It was literature that facilitated the emergence of a new Aleksandar Hemon from the primordial soup of his own self, that could connect his purgatorial state with a lost past and homeland. Publishing his first short story collection in 2000, he was part of a cohort of writers—Ha Jin, Jhumpa Lahiri, Zadie Smith, Joseph O’Neill, Teju Cole—whose work plumbed the no-man’s-land between cultures, searching for a coherent sense of self in a globalized world.

In 2019, the exile cuts a different figure. There is less interest these days in the existential trials of the uprooted; attention has shifted to those malcontents who, we are told, have become strangers in their own land. At the same time, the idea that a person can create their own identity runs counter to a growing understanding of the ways in which race, gender, and class frame experience. Hemon understands these issues, too, having grappled over the course of his career with his maleness, his whiteness, and his yearning for a vanished motherland. But it is only in two new books of nonfiction—My Parents: An Introduction and This Does Not Belong to You—that he really comes to terms with the limits of individual agency, and the grim prospect that there may be no salvation for the exile after all.

My Parents is the story of how Hemon’s mother and father fled wartime Sarajevo to settle, never quite comfortably, in the frigid climes of Ontario, Canada. This Does Not Belong to You presents a series of linked vignettes from Hemon’s childhood and adolescence. The former is a straightforward tale of love (of life, family, country) and loss (of everything); the latter is an impressionistic, experimental evocation of a past turned to rubble by both war and the grinding passage of time. These two new books are bound together in a single volume: As soon as you finish reading My Parents, you flip the book over and begin reading This Does Not Belong to You in the other direction; the two books meet, like hemispheres, in the middle. Together, they constitute the poles of Hemon’s world: history and memoir, reality and myth, realism and the avant-garde.

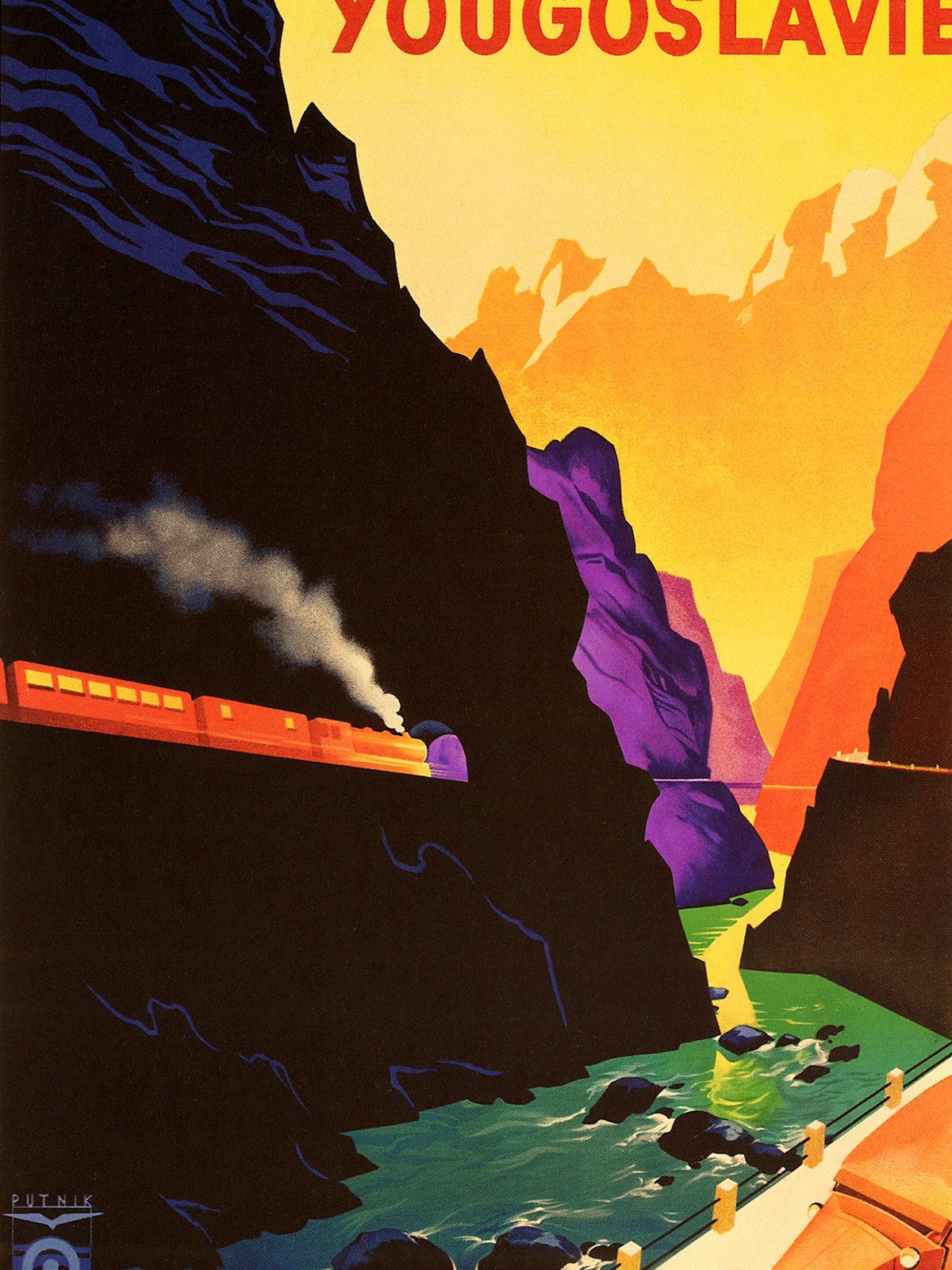

Of course, the book can just as easily be read in the opposite order, moving from Hemon’s prewar youth to his parents’ postwar travels and travails. But it feels appropriate to begin with Petar and Andja Hemon’s sad saga, which, like the Book of Genesis, chronicles a family’s (and hence humanity’s) exile from paradise. One of the book’s challenges is identifying that paradise with any precision. The Hemons hail from a part of Europe that has long been overwhelmed by the oceanic movements of empires and great powers. As the Ottoman Empire receded from the Balkans in the late nineteenth century, the Austro-Hungarian Empire swept in. The catastrophe of World War I, precipitated by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, unmoored the empire’s provinces. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was eventually formed, populated by Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Bosnian Muslims, and all the displaced of a disintegrated empire, drifting in from what are now Poland, Ukraine, and the Czech Republic. Andja is of Bosnian-Serb descent, while Petar’s family has roots in Ukraine, which even now, more than 100 years after the last Hemon left Galicia with a steel plow in hand, exerts an implacable pull on Petar’s heart. “Our family has left behind a trail of homelands,” Hemon writes. “Our history is the history of an unassuageable longing for the home that could never be had.”

The German invasion of Yugoslavia in World War II tested the young country’s integrity, pitting its motley slew of ethnicities against each other. (In one of the footnotes that run throughout the text, Hemon notes that the genocidal pogroms of Croatia’s fascist puppet state “appalled even some Nazis.”) But it was out of the crucible of the war that Josip Broz Tito’s Communist Party, the core of the anti-Nazi resistance, emerged as a uniting political force that allowed Yugoslavia to thrive until Tito’s death in 1980. And here, perhaps, are the coordinates in time and space where we can locate the Hemons’ Eden: a postwar period of socialist uplift that vaulted millions of families, including the Hemons, into a vibrant middle class.

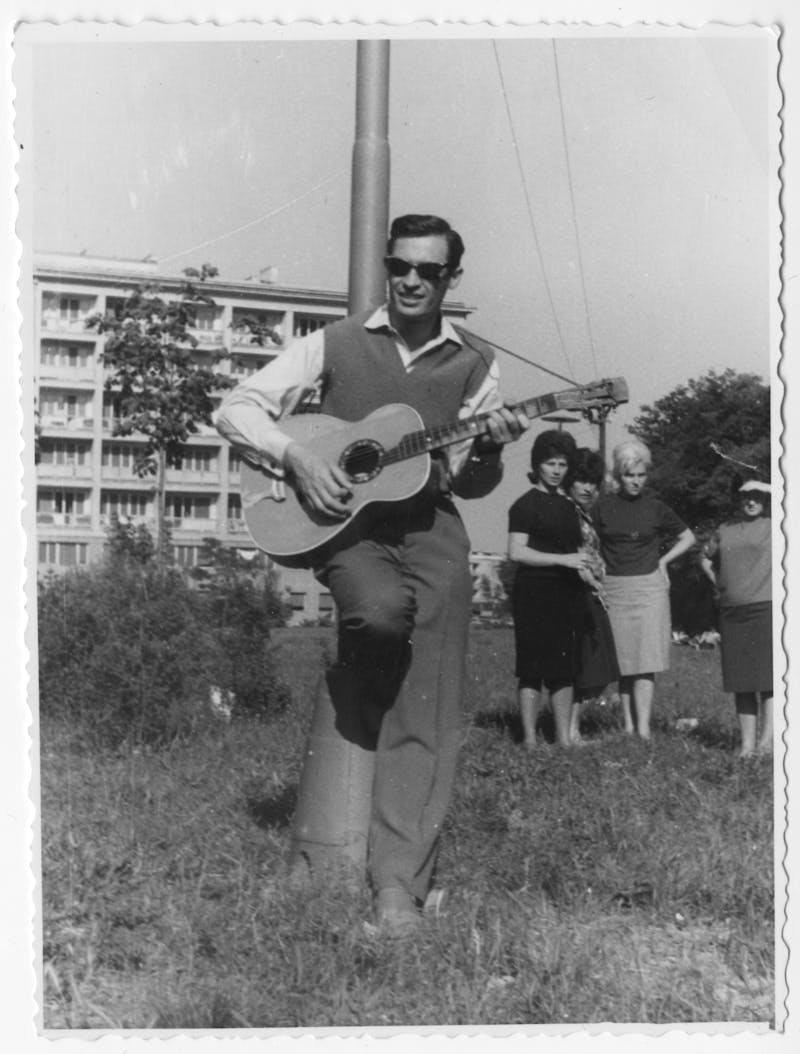

Whether Tito’s Yugoslavia was destined to break apart without the superglue of his personality, and whether Tito was too much of an authoritarian to warrant the esteem of our supposedly more enlightened era, are questions that Hemon addresses quickly (no and no, respectively). His main interest is in re-creating the socialist quasi-utopia that sustained and shaped his parents’ generation. He invokes the government’s overarching doctrine of brotherhood and unity (bratstvo i jedinstvo), the roads and railways voluntarily built by youth brigades (omladinske brigade), the patriotic songs these youths sang to enliven their spirits (“Comrade Tito, you white violet / all of youth loves you!”), and the state corporations, Elektroprenos and Energoinvest, that provided his family with income and a place to live. More than mere sustenance, Yugoslavia provided his family, especially his mother, with a sense of collective purpose that trickled down into a sense of self. “She built the country as she was building herself,” Hemon writes.

The Hemons were fortunate to get the last train out of Sarajevo when the war started, and to then win asylum in Canada, but their lives effectively ended when their country ceased to exist. Of his mother, Hemon writes, “Overnight she became a nobody, she often says, a nothing.” His mother’s story is his own: He knows from painful experience that people are arbitrary beings; that who we are can change in an instant, simply by being dropped into a new environment; that the way we view ourselves can suddenly be at odds with how the world sees us, producing a doubled sense of self. His lifelong project, in many ways, is an attempt to reconcile those two people: the penniless, bumbling foreigner who speaks atrocious English, and the cocksure Sarajevan who was once intelligent and cool and desirable—who was somebody.

His parents undergo indignities familiar to immigrants the world over, working jobs that are well below their levels of education, accomplishment, and self-respect. They naturally obsess over the differences between their new home and the old, as Hemon elucidates in a discussion about food:

Among my family in Canada and their friends, much time was spent debating dietary and other differences between “them” (Canadians) and “us” (people from Bosnia and the former Yugoslavia): “Their” bacon was soggy; “they” didn’t know how to make sausage; “their” sour cream was not thick enough; “they” didn’t eat things we ate; “they” were fat and incapable of truly enjoying life because “they” worried about getting fat all the time.

But the Hemons struggle to bounce back, to transcend their nobody-ness. They are simply too old, in their fifties when they arrive in Canada. While they may have been middle class in Yugoslavia, they come from peasant stock and are too unworldly to flourish in a frosty, alien culture. But more than anything, their past lives are too bound up with Yugoslavia. The prizes that they won from the government and that bolstered their self-esteem; the savings they amassed and hoped to pass on to their children; the patriotic songs they sang, the academic degrees they earned, the lives they painstakingly built—all meaningless, gone. It is perhaps hard for people in the West, taught from an early age to see themselves as self-reliant individuals, to appreciate just how much country forms the warp and weft of their lives. But if your homeland were to disappear tomorrow, you would, in a way, disappear, too.

The Hemons take solace in what remains: food, Ukrainian folk songs, Petar’s beekeeping practice (a hobby that crops up again and again in Hemon’s fiction). “I can identify with my father’s striving to find and protect a domain in which he can practice agency with dignity and some form of sovereignty,” Hemon writes. “What beekeeping is to him, literature is to me.” His parents’ lives are tightly centered around their house, a refuge from the coldly indifferent Canadian landscape, where they can cook their own food, speak their own language, and be themselves. Still, there is no escaping the taint of exile: “They make their food to taste of home, but it inescapably ends up having the taste of displacement,” Hemon says.

As a writer, Hemon is exact, unsentimental, cerebral. That is not to suggest that he is aloof or unfeeling. Quite the opposite: There is an ocean of pain underneath his prose, and his brainy stoicism is the raft that prevents him from drowning in it. “If only I could afford to succumb to this depleting sorrow, to stop walking with my chin up, and just collapse, like a smashed box, things would be much simpler,” he writes in his 2002 novel Nowhere Man. Though he has mastered English, each sentence seems hard-won, forged from scratch, with nothing ready-made to rely on. He also has the zeal of the late convert, evident in his diamond-precise syntax and his hundred-dollar vocabulary. At some point while reading his oeuvre, I began circling words that, I’m quite sure, I had never seen before: nacreously, feculent, stertorous, chitin, caliginous, cothurni, crepitating, edentate.

This Does Not Belong to You represents a step forward in Hemon’s relationship with the written word. Or maybe it’s a step back. The confidence of his earlier work has now been checked by a pervasive doubt—about literature’s ability to create order and meaning, and to put a broken life back together. The book’s vignettes, many only a paragraph long, are like flashes of memory: a boy walking the streets of Sarajevo, a boy lying sick on the couch, a boy being bullied. Interspersed are ruminations on what these memories might mean, as if Hemon is turning them in his hands like a Rubik’s Cube, unsure how they fit together. The Proustian faith in memory—that it binds us to the past, that it gives a sense of unity to our otherwise desultory lives—has been shaken. And once that goes, the whole edifice of his life as an exile-cum-writer starts to waver. “What if there was no whole self?” he wonders. Later, he says, “It occurred to me just yesterday that I’d been wrong about everything, entirely wrong from the very beginning.”

The cause of this crisis is difficult to pinpoint. There are also plenty of instances in which he reaffirms literature’s redemptive power. “Language … dropped the rope for me to climb out of oblivion,” he writes. Still, the story of his parents, as they approach the end of their lives, seems to have given him second thoughts. In My Parents, he records a heartbreaking conversation with his mother: “When I asked her whether she’d say that her life was good overall, she said: ‘No, it was not. Because of the war.’” It really is that devastatingly simple, making a mockery of literature’s airy claims to salvation.

Hemon’s awakening sense of his own mortality is a factor as well: “Now I know that the amount of life available is fixed and horribly small, that we could soon run out of it, and I’m running out of it.” He now suspects that the only time he was truly alive was when he was young, because that was when he lived life to the hilt. There was no need for writing then, no space for it, because there was no gap between him and the world. He struggles with the question of whether writing can really return life to us, or if the desire to write is the foremost evidence that life is constantly draining away. And everywhere he sees nothing but loss—of his home, his self, his family. “There was a here that belonged to us, that was us,” he writes. That “here,” that “us,” are no more.

If even a writer who possesses the gift of crystallizing life into literature cannot reverse the exile’s curse, it complicates the idea that identity is defined by its holder. Hemon grudgingly admits this: “He who defines personal identity—that is to say, me—as the private possession of some depository of memories is mistaken. Fine.” Identity is composed of individual experience, yes; of race and gender, clearly, both of which undoubtedly facilitated Hemon’s reinvention as a successful Bosnian-American artist. But identity is also composed of a physical place that exists outside ourselves, a “here” that constitutes an “us,” whose essence is magically preserved in objects like the honey of a Bosnian bee, and whose hold on us cannot be dismissed as chauvinistic fantasy.

Hemon’s crisis in This Does Not Belong to You also undermines the writer’s greatest conceit: that by describing the world truthfully he can somehow control it. If the last few years have shown us anything, it is the power of cataclysmic events to shock and confuse. We know, in our bones, that control is an illusion. We fall ill; we fall in love with someone we shouldn’t have; we live in countries that, for reasons we don’t quite comprehend, start to fall apart. If “true history is always played out on a personal level,” as Hemon writes, then our moment has found its expression in a loss of faith in ourselves to determine what kind of people we will be and what the future will look like.

Great literature still provides its comforts, however. Of the many words I learned reading Hemon’s beautiful, big-hearted books, my favorite is Bosnian, not English: sevdah, which Hemon describes as “a pleasant feeling of losing oneself to the hopelessness of love, to time passing, to life and the defeats it inflicts.” I like to think that, when the flood bears me away, I will be filled with this feeling.