On the morning of July 24, Senator Joseph Biden, his face contorted with rage, stared out from the pages of the New York Times, the Washington Post, and other newspapers. At a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing the previous day, he had erupted in a tirade at Secretary of State George Shultz over the Reagan administration’s policy toward the South African government, “We ask them to put up a timetable,” he said. “What is our timetable? Where do we stand morally? ... I hate to hear an administration and a secretary of state refusing to act on a morally abhorrent point. ... I’m ashamed of this country that puts out a policy like this that says nothing, nothing ... I’m ashamed of the lack of moral backbone to this policy.” Shultz insisted the administration’s policy had “tremendous moral backbone.” “What we want,” he explained, “is a society that they can all live in together. So I don’t turn my back on the whites and I would hope that you wouldn’t.” To which Biden responded, “I speak for the oppressed, whatever they happen to be.”

His performance might have struck some as insufferable moralizing, made worse by his incivility to Shultz, whose courtesy and patience are much appreciated on Capitol Hill. But it was vintage Biden. And it illustrates both his strengths and weaknesses as a probable candidate for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. Biden, 43 years old, is winning rave notices on the party speaking circuit as a dynamic and gifted orator with the courage to stand up to his party’s entrenched interest groups, and the skill and passion to make them like it. Around the Senate, however, with few exceptions his record has been that of a reliable ally of those interest groups. And the rhetorical fervor of his stump speeches and debating style have earned him the reputation of a man whose mouth often runs—and runs, and runs—well ahead of his mind.

Indeed, Biden gives the impression of utter spontaneity. It is an uncommon and in some ways charming quality, but it frequently gets him into trouble in the Senate. There was, for example, the defeat snatched from the jaws of victory the day Daniel Manion’s nomination as a federal appellate judge came before the full Senate. Biden was the Democrats’ floor manager. After stalling for days in the hope that opposition to Manion—a conservative of scant judicial credentials—would build, the Democrats suddenly announced they were ready to vote. Majority Leader Robert Dole, who had been calling all day for an immediate vote, found himself in the excruciating position of having to admit on the Senate floor before a crowded gallery, with the TV cameras rolling, that he wasn’t ready. Dole explained sheepishly that two members were out of town. Suddenly, and to the obvious surprise of Democratic leader Robert Byrd, Biden offered Dole two pairs—that is, to hold back two Democratic votes against Manion (including his own) to offset Dole’s absentees, in exchange for an immediate vote. Dole could hardly say no, and the vote began.

In the hallways, civil rights lobbyists said the Democrats had 51 firm votes and could afford to give away two, especially with the Republicans two short. But Republican Slade Gorton of Washington, who had opposed Manion because he had been unable to get a desired judicial appointment through the Justice Department, suddenly got the promise he had been waiting for and switched sides. The Democrats were still ahead, but at the last minute Republican Nancy Kassebaum of Kansas switched from voting against Manion to a pair with the absent Barry Goldwater. That left the vote tied and meant that Vice President Bush, presiding, would inevitably cast the deciding vote for Manion. “Mr. President,” Biden suddenly blurted, “I withdraw my pair. I vote no.” Then, moments later, “Mr. President, never mind. Forget I said that.” Byrd then did the only thing he could do and switched his vote to be on the winning side, so that he would be eligible under Senate rules to move to reconsider the vote. He did, but the matter was put off, and by the time the vote occurred weeks later on the motion to reconsider, the Republicans had enough votes to muster a tie that Bush broke in Manion’s favor.

Biden would later explain that his decision to grant the two pairs had been a calculated gamble, based on his belief that four of the commitments he held against Manion would be good for that day only, and that the four senators in question inevitably would yield to pressure afterward and back Manion. But the fact is, a winning position had been turned into a lost vote. And it is almost painful to imagine how a comparable episode, with Biden’s quickly retracted outburst about withdrawing his pair, would have been treated in the heat of a presidential campaign.

Biden, however, seems unworried. “One thing that has changed in the last three years,” he says, “is I really feel good about myself and where I am.” Certainly Biden has come some distance from the bitter and haunted young man who came to the Senate 14 years ago after suffering the terrible tragedy of his wife and infant daughter’s death in an automobile accident a week before Christmas 1972. For years Biden was suspicious and standoffish, with a special distaste for the press. He was best known for the fact that he went home to Wilmington, Delaware, every night on the Metroliner to be with his two young sons, returning in the morning. It is a practice he continues to this day, but since his remarriage in 1977, his outlook has brightened. “I’m proud of what I do in the Senate,” he says, “confident I’m ready, and absolutely confident we are on the verge of a real change in the mind-set of this country.”

This last is Article One of what might be called the Pat Caddell Credo, the beliefs that gave us the Gary Hart campaign of 1984—after Caddell failed to persuade Biden to make the race. It has led some to think that both Hart and Biden are merely creatures of Caddell’s kingmaking ambitions, spokesmen for viewpoints gleaned from his polling. But Biden claims credit for the idea that the Democratic Party had lost its appeal to a generation of younger voters by seeming too subservient to the party’s interest groups and too pro-government. He has speeches going back to well before 1984 to support him. “The fact is,” he said in 1980, “that government has become too large. It regulates too much and it taxes far too much.” In 1981 he told the National Young Democrats Convention, “The Democratic Party is simply out of touch as a national party.” Wrested from their context, these words sound harsher than they were, and they’re hardly radical stuff anyway. But they’re a far cry from anything Walter Mondale was saying in 1984.

In September 1983, Biden made a thunderous speech that sounded sharply critical of his party to the New Jersey State Democratic Convention. “America is in serious trouble,” it began, “and so is the Democratic Party. As every hour passes, our ability to shape the American future is slipping from our grasp. . . . Instead of thinking of ourselves as Americans first. Democrats second, and members of special-interest groups third, we have begun to think in terms of special interests first and the greater interest second.” The speech, whose concluding note was an emotional call to action built around a quote from Robert Kennedy, drew a standing ovation and tears in the eyes of many. After that Caddell, who had long been Biden’s pollster, began a protracted effort to get him to run for president. Biden listened at length, but finally concluded the time wasn’t right. For one thing, he was up for re-election that year, which meant the race would be a White House-or-bust proposition.

Now Biden has all but decided to run in 1988. And he’s taken seriously. Bill Bradley, himself sometimes mentioned as a possible Democratic candidate, says Biden is “the best speaker in the Senate.” Tom Donilon, a political operative who worked in successful nomination campaigns with Jimmy Carter in 1950 and Mondale four years later, likes Biden’s chances. “He can appeal to voters in Iowa and New Hampshire, and he’s still someone who can go South,” Donilon says, noting that Biden’s recent speeches have been enthusiastically received in all parts of the country. And he says Biden may be the only potential Democratic nominee who can do what many think someone will have to do if the Democrats are to win: stand up to Jesse Jackson without losing black votes.

Biden has a reputation for telling off people in his party without making them dislike him. “You know why?” he says. “It’s because they know I’m really with them.” He certainly is, and this is critical to understanding Biden and his message. For all his rhetoric about special-interest groups and the need for change in the Democratic Party, Biden’s record has largely been that of an orthodox liberal Democrat who gets consistently high ratings from the groups that make up the traditional Democratic coalition. In 1984, for example, the AFL-CIO gave him an 84 percent rating, the Americans for Democratic Action an 85. He has long opposed racial ‘’using and thought criminal rehabilitation a mirage. But these are the exceptions.

He voted against tuition tax credits, for the Martin Luther King holiday, and against overturning the Supreme Court decisions allowing abortion and prohibiting school prayer. In keeping with his view that the government taxes too much, he has gone along with both the Reagan tax cut of 1981 and the Senate version of the current tax reform bill. But Biden has never departed from the concept of taxing the rich and redistributing the wealth, which has been a large part of the old-time religion of American liberalism. For example, he twice voted to hold the Reagan tax cut to one year, and also to limit its benefits to upper-income taxpayers. And although he supported his Democratic colleague Bill Bradley’s ideas when they came to the Senate floor this year in the form of the Finance Committee’s tax reform bill, he also voted in favor of the Mitchell amendment. It would have added an additional, higher tax bracket for the and was strongly opposed by Bradley and other tax form advocates. Indeed, the Mitchell plan was regarded as a “killer” amendment, one that would have fractured the broadly based coalition of interests that had rallied behind the bill. It was overwhelmingly defeated. Despite Biden’s occasional criticism of Big Government, he says, “People haven’t lost faith in in government. They’ve lost faith in the ability of a Democrat to manage the levers of power.”

In foreign policy, Biden was against the MX, for the nuclear freeze, against military aid to El Salvador, and against aid to the contras in Nicaragua. He has been deeply involved in the effort to keep SALT II alive. And, of course, he has passionately pushed for sanctions against South Africa. At the same time he says that the Soviet Union has also been a major human rights offender and that he favors improved relations with the Soviets: “There are no absolute rules in the conduct of foreign policy.” Biden is fond of saying that he “came out of” the American civil rights movement of the 1960s, and he finds an important parallel between it and events in South Africa. He believes the movement gives the United States a special responsibility for leadership on the issue of apartheid. Though he acknowledges that the United States may have only a marginal effect on South Africa, he says, “Sometimes you take actions even though they won’t affect anything but because they’re right.”

In view of his record on civil rights issues, it isn’t surprising that Benjamin Hooks said in introducing Biden recently at the NAACP convention in Baltimore, “When the NAACP needed you, you were there.” Biden made headlines that day for criticizing Jesse Jackson. But this is what he said: “You must reject those voices in the movement who tell black Americans to go it alone, who tell you that coalitions don’t work anymore... that only blacks should represent blacks.” That’s all. Jackson was never mentioned by name. The speech was largely devoted to a blistering attack on the Reagan administration’s civil rights record. At a press conference afterword, reporters succeeded in getting Biden to say that Jackson “does not know what he’s talking about on Libya, does not know what he’s talking about on economic policy.” But he also said, “Jackson has done some really phenomenally good things.” This is a standard Biden tactic; some general criticism generously leavened with praise, often including himself among the targets of criticism.

Biden is able, as some politicians are not, to laugh at himself, and he has an irrepressible, boyish personality that makes him hard to dislike. He says he has even come to enjoy reporters, and expects to know how to deal with the national press corps by the time he makes a final decision on running for president. Yet when he first learned this article had been commissioned, to a reporter not known, as his longtime press secretary Pete Smith put it, “as one of Biden’s greatest fans,” the senator telephoned the editor in chief of this magazine and tried to have the assignment called off. When that failed, he at first refused to sit for an interview, agreeing only to a preliminary informal chat over coffee, after which he would decide whether to cooperate. “I just want to find out why you don’t like me,” he said at the beginning of that chat in the Senate dining room. It was an awkward and extraordinary conversation, in which Biden finally asked if the reporter harbored any “deep personal antipathy.” He was assured that there was none. “Then what is it you don’t like?” he asked. “Senator,” came the reluctant reply, “I think you’re a windbag.” Biden seemed greatly relieved, laughed, and said he thought there was truth to that. He agreed to cooperate fully.

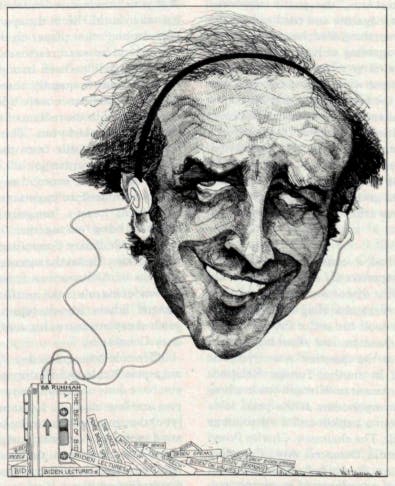

Biden has long had a considerable reputation among Capitol Hill reporters for enjoying the sound of his own voice. On the first day of the highly publicized confirmation hearing of Alexander Haig as secretary of state, for example, Biden took his entire first turn—ten minutes—to ask a single question, and when he was finished it was unclear what the question was. Everyone laughed, Biden included. In another Foreign Relations hearing a year later, he went on at such length late in a long session that broadcast correspondents at the press table fashioned a white flag from a napkin and a microphone pole and waved it in the air. The chairman, Charles Percy, howled with laughter, as did Democrat Alan Cranston. Biden seemed not to notice. Reminded of the incident, Biden said he knew he had a tendency to go on too long but had now curbed it. Only a few days later, at a joint news conference with Republican Senator William Cohen of Maine on legislation to keep SALT II alive, he spoke for more than 30 minutes before Cohen got a word in.

Biden has been well-positioned in terms of seniority and committee assignments to develop a major legislative record. As the Judiciary Committee’s ranking Democrat he did play an important role in the 1984 enactment of a sweeping rewrite, 11 years in the making, of the nation’s criminal code. Colleagues credit his contribution on this bill to his ability to get along with the committee’s onetime Dixiecrat chairman, Strom Thurmond, a man nearly twice Biden’s age with a distinctly different political background. On the Foreign Relations Committee during the SALT II debate, Biden became an acknowledged expert on the treaty, and has been a leader of the renewed effort to keep it alive in the face of the Reagan administration’s desire to let it die. He says he was “the single most active” Democrat on the Intelligence Committee, a claim that is hard to assess, since the committee’s proceedings are almost entirely secret. Biden says he “twice threatened to go public with covert action plans by the Reagan administration that were harebrained,” and thereby halted them. Committee rules forbid him from saying what those plans were.

But aside from his role with the SALT II treaty, which the Senate did not ratify, and the careful aim he has taken at the fish in the apartheid barrel, Biden has not been an important player on the Foreign Relations Committee. And he was no factor at all on the Budget Committee, although it has been an important arena in the Reagan years. He was frequently absent from meetings, and his periods of attendance were brief and marked by obvious impatience with the tedium of the proceedings. He got off that committee last year. “The Budget Committee is useless,” he says. Aside from the crime bill, Biden is not associated with any major bill.

Still, he says he is proud of his role in the Senate and considers himself an important force in the party caucus. “Joe Biden,” he says, “can go to both liberals and conservatives and bring ‘em together.” Biden has taken an active role in the Judiciary Committee in opposing some Reagan nominations. He led the successful fight to defeat Jefferson Sessions of Alabama as a federal judge. But he is better known for his role in the confirmation battle over Attorney General Edwin Meese, especially for his lengthy, anguished explanation of his vote against Meese in the Judiciary Committee.

Biden told Meese that day, “I have concluded that you are a personable and likable man. I have concluded that you have done no criminal wrong and I do not believe that you are unethical. .. . I just never found a case about [you] that you are—I have not been able to conclude in my mind, you are an unethical man. I have not been able to make that conclusion. So if all those things are there, why, why do I find it so difficult to vote for you? And I finally figured it out. It relates less to you than it does to the office of attorney general. I think some would say ... that I have maybe an idealistic and unrealistic view of the office of attorney general. But I think it should be occupied by a person of extraordinary stature and character.”

If Biden’s speech sounded to some suspiciously like the rationalizations of a politician looking for a way to vote against a nominee in spite of the evidence, to others it came across as a heroic statement of conscience. The editors of the Washington Post published it in its entirety on their op-ed page. Still, it reinforced the impression of Biden as a man who does much of his thinking out loud and sometimes has difficulty figuring out what he thinks. And that, ultimately, is the most enduring impression Biden leaves. It suggests that a Biden campaign for the presidency would be colorful, newsworthy, and, unlike his oratory, brief.