It may be hard to believe now, but for a New York minute it seemed that Bill de Blasio was going to be the champion of an insurgent left. Progressive activists and commentators hailed de Blasio’s landslide victory in New York’s 2013 mayoral election as a sign of an encouraging new direction for the Democratic Party. His unabashedly liberal campaign—which centered on income inequality, or what de Blasio poetically termed a “tale of two cities”—prefigured the unrest that would shake the party, culminating in Bernie Sanders’s unlikely challenge to Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential primary.

De Blasio’s 2013 platform, which The New York Times called “the meatiest material presented by any candidate” in the field, sounded themes that are now standard fare for Democrats with national ambitions. He promised a universal pre-kindergarten program, paid for by a tax on the wealthy; an identification card that would allow undocumented immigrants to access city services; an ambitious plan to build or preserve 200,000 units of affordable housing; and reform of stop-and-frisk, the Bloomberg-era program that effectively allowed police to target minorities with warrantless searches. “Government must focus on the needs of families, must be the protector of neighborhoods, and must guard the people from the enormous power of moneyed interests,” de Blasio thundered in his campaign announcement.

Democratic voters rebuked twelve years of plutocratic rule by handing de Blasio a primary victory over the Bloomberg-favored Christine Quinn.* As Peter Beinart wrote in The Daily Beast, “De Blasio’s victory is an omen of what may become the defining story of America’s next political era: the challenge, to both parties, from the left.” He added, “It’s a challenge Hillary Clinton should start worrying about now.”

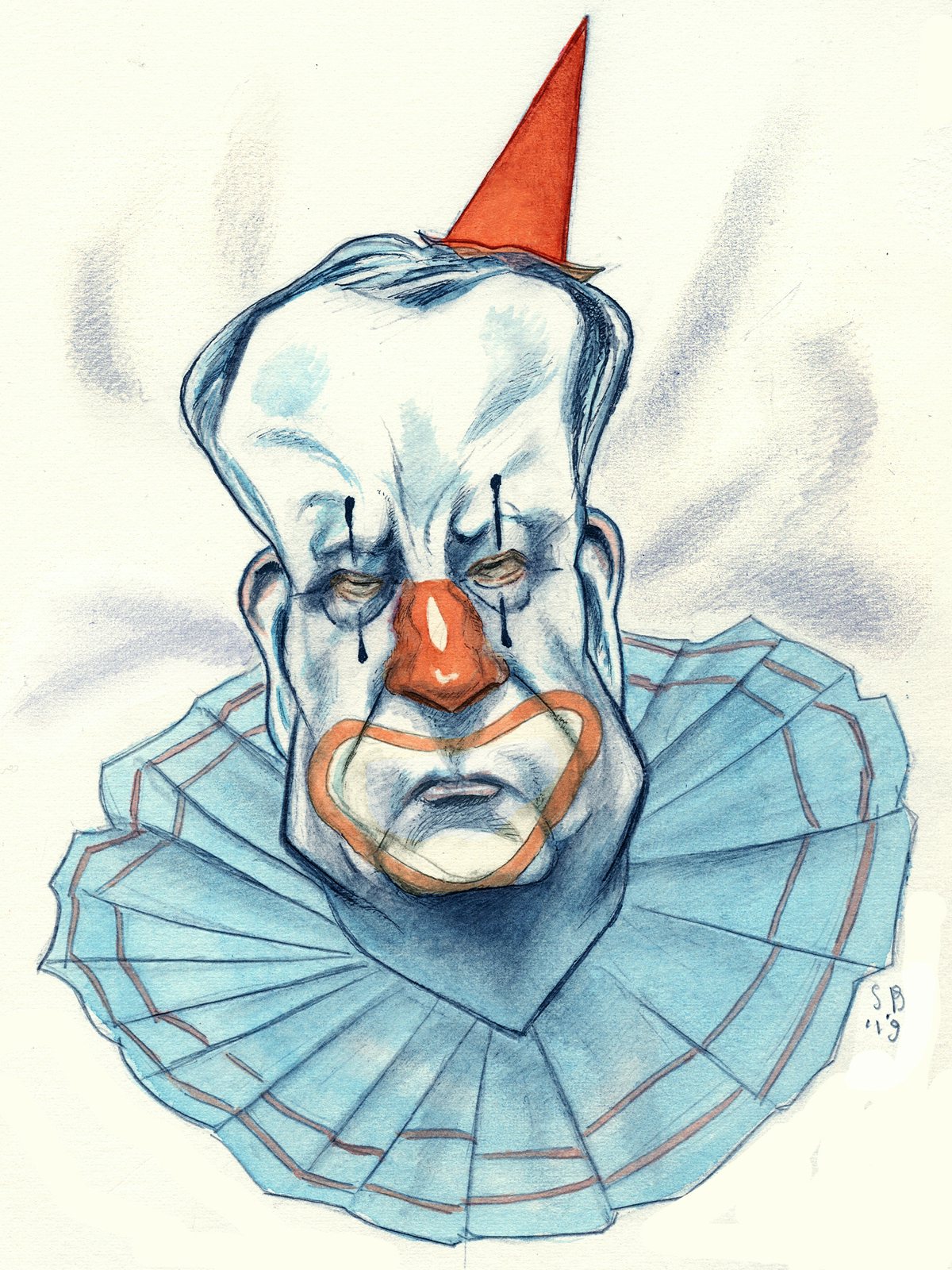

Yet as de Blasio weighs entering the 2020 race, the prospect of a President de Blasio has been met with widespread derision. The New Republic’s Alex Shephard termed his interest in the presidency an “embarrassing quest for national fame,” while the mayor’s own allies (anonymously) told Politico that his flirtation with a presidential run was “fucking insane.” De Blasio’s wife, Chirlane McCray, has said the “timing is not exactly right” for him to launch a campaign. The New York Times, which seems to take gleeful pleasure in dinging de Blasio for everything from calling errant snow days to ostentatiously hanging around Iowa, recently noted that Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, has generated far more presidential buzz than the mayor of the country’s biggest city. Even in his hometown, there seems to be only one person who thinks a de Blasio presidential campaign would be anything other than a joke: de Blasio himself.

How did he fall so far? De Blasio does, after all, have a robust record of actual accomplishments under his belt, which is more than what can be said for, say, Beto O’Rourke. He was once the favorite of grassroots groups and leftist elites alike. Perhaps the left soured on him because he is a singularly ham-handed politician, who possesses all the native charm of a Howard Schultz, the billionaire Starbucks founder who is trying to win the presidency one sanctimonious tweet at a time. Perhaps de Blasio has never been as progressive as his early cheerleaders made him out to be; he might simply be an opportunist who saw, early on, the way the wind was blowing and adjusted accordingly. Or maybe the Democrats, unnerved by the disaster of the last election and fearing another Trump victory in 2020, have started to prefer candidates who are all promise and no baggage.

In retrospect, de Blasio was always a strange fit to lead a revived left. He came up through the New York Democratic establishment, serving as the 1994 campaign manager for the legendary, ethically challenged U.S. Representative Charlie Rangel and for Clinton during her 2000 Senate run. At the same time, his 2013 campaign was memorable for fringe positions well beyond the scope of even the modern-day left, particularly his call to curb the city’s horse-carriage industry (a coalition including animal-rights activists spent $1 million attacking Quinn during the primary and were an energetic force behind de Blasio’s election). He was a weird mix, beholden to certain entrenched industries—most notably real estate, which has only further exacerbated the city’s wildly unequal political economy—but comfortable occupying the party’s left flank.

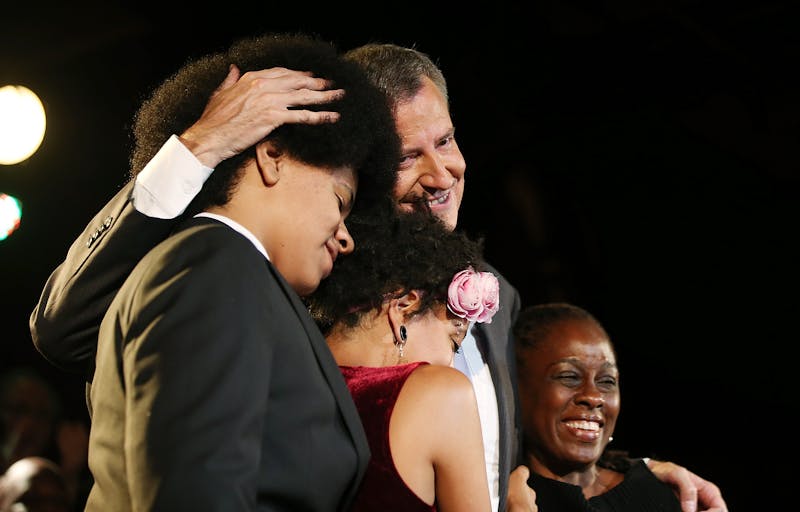

But de Blasio did represent one clear change: He was not Michael Bloomberg. More than anything, his reputation as a left reformer stemmed from his position on overhauling the New York City Police Department and checking stop-and-frisk, a desperately needed corrective that tied in neatly with his own story as the head of a mixed-race family. The race against Quinn really turned after de Blasio ran an ad narrated by his teenage son Dante, which made plain that stop-and-frisk was personal for him. The city’s minority communities, a crucial voting bloc, swung for de Blasio in a big way. And while de Blasio is now better known for his gaffes and general awkwardness—a kind of real-life Gumby who accidentally kills groundhogs and works out in knee-length cargo shorts—he was once seen as charismatic, his whole family drawing cheers for a dance called The Smackdown.

Upon assuming office in 2014, he quickly racked up some big wins, no small feat in a city that had seen decades of centrist-to-conservative rule (before Bloomberg there was Rudy Giuliani, who is now busy incompetently covering up Donald Trump’s various alleged crimes and misdemeanors on television). Furthermore, de Blasio did all this while toiling in the substantial shadow of New York’s conservative Democratic Governor Andrew Cuomo, an erstwhile ally who has a habit of undercutting left-leaning priorities and who eventually became de Blasio’s ruthless tormentor. The two of them sparred in the city’s overheated mediasphere over a vast array of tabloid-friendly issues, such as topless women in Times Square, the death of a deer, and the city’s decrepit subway system.

But before de Blasio and Cuomo well and fully fell out, de Blasio managed to push through his universal pre-K plan, enrolling some 70,000 children in over two years, equivalent to three-quarters of the entire population of South Bend. He made free lunch available to all public school students. He raised the minimum wage for city workers to $15 an hour and has put forward a proposal for New York City employers to provide paid sick leave to their workers. He made good on his promise to provide municipal ID cards for undocumented immigrants, allowing them to obtain services that were previously unavailable to them, such as opening bank accounts or accessing public libraries.

Yet none of this has added up to the reputation of an accomplished mayor. Why not?

To start, de Blasio has a terrible relationship with the press, which is as much de Blasio’s fault as it is the handiwork of New York’s scandal-happy media scene. De Blasio has a penchant for talking down to journalists, such as when he sullenly told a New York Post reporter that he had “no use for a right-wing rag that attacks people who are good public servants and tries to undermine their reputation.” In the wake of such outbursts, both liberal and conservative papers love to drag their mayor, which is why the first image New Yorkers have of de Blasio is not of him cutting the ribbon on a new pre-K school, but of him being chauffeured in a black SUV across town to the Park Slope YMCA to work out. It is a habit that he apparently believes keeps him in touch with his middle-class roots—which serves as a perfect, if inadvertent, example of how de Blasio’s own cluelessness and the press’s venom combine to ratchet up his reputation for self-righteous victimhood.

“I would argue that de Blasio has had many strong successful progressive policies, more so than many of the other candidates running in the race,” Rebecca Katz, a former top adviser to de Blasio’s 2013 campaign, told me. “But most of that is overshadowed by his toxic relationship with the press corps that covers him.”

It’s hard to determine when exactly it all went south with the press, but the 2016 primary between Clinton and Sanders was definitely a turning point. In what came off as a real-life equivalent of the distracted boyfriend meme, de Blasio held off endorsing his former boss for six months, as he gazed longingly at the Sanders campaign and the stir it was creating on the left. He created a nonprofit group, Progressive Agenda, that reportedly spent nearly $900,000 to boost his policy priorities on income inequality—in part by sponsoring a presidential forum in Iowa that was eventually canceled because so few candidates agreed to attend. As Politico later reported, “The mayor’s role in the event seemed the biggest hurdle in getting others to sign on.”

His foray into national politics ended disastrously when he ended up backing Clinton anyway, sending a convoluted message of where his loyalties lay. Though he officially endorsed Clinton, it was evident that his reluctance was meant to pull her campaign further left. The result was a failed accommodation to the Democratic frontrunner that, for de Blasio, represented the worst of both worlds: He simultaneously seemed to spurn the Sanders left while angering the Clinton establishment for dragging his feet. For someone who wanted to play kingmaker, de Blasio transformed his 2016 campaign misadventures into a long and largely pointless show of penance, wandering the cold streets of Iowa to knock on doors for Clinton.

In addition to revealing that he is not the most nimble politician, the Iowa debacle made clear that de Blasio wants very badly to be a national figure—and New York’s hostile press has gleefully flogged this uncomplimentary storyline ever since. Most members of New York’s press corps don’t like the idea that their city is playing second fiddle (even if it is to the nation as a whole), and so they routinely accuse de Blasio of putting his own ambitions above the city’s concerns. The perception that de Blasio thinks he’s too good for New York has dragged down his poll numbers, with a full 76 percent of New Yorkers saying he should stay home rather than run for president.

And the will-he-or-won’t-he dance with Clinton suggested that de Blasio was just another on-the-make political opportunist, with a commitment to left politics that’s purely conditional. That seemed to dispel the “tale of two cities” mystique once and for all.

Was de Blasio ever that liberal to begin with? His critics say no, that he’s always been the regular old typecast of a calculating politician. It’s impossible to ignore the distinctly Dickensian feel of New York City in the de Blasio years. New York’s education system remains one of the most segregated in the country. Rikers Island, the city’s notoriously abusive jail complex, won’t be fully shuttered until 2027. And while much of the blame for the crumbling subway system goes to Andrew Cuomo and the state government in Albany, de Blasio has not escaped the ire of the city’s millions of commuters. After he made a big deal about riding the subway once to show solidarity with disgruntled straphangers, Splinter’s Hamilton Nolan wrote, “Wow!!! Break out the cameras!!! Mr. Mayor, I want to see you in the god damn tunnel for the next seven hundred days of your term or fuck off man.”

De Blasio has also taken a lot of heat for the city’s housing crisis. He may have done more than his predecessors to address the wretchedly unequal state of New York housing, but advocates regularly blame him for cutting deals that give too much away to developers at the expense of low-income New Yorkers. “I think that’s where de Blasio’s values and ideals come into contradiction with his actions,” Jonathan Westin, executive director of New York Communities for Change, told me, pointing out the Bedford-Union Armory deal that granted public land in Crown Heights to a private developer. “He still wanted to be mayor and govern in a similar fashion to Bloomberg. That’s clearly a big contradiction towards where the Democratic Party is going.”

His administration has also made a hash of the New York City Housing Authority, which provides housing for more than 400,000 residents and is mired in lead paint scandals and chronic heat and hot water failures. NYCHA’s problems stem from decades of funding cuts both at the federal and state level, but critics have also called out de Blasio for general neglect. “If we want to talk about being a progressive mayor, part of progressivism is having those conversations of big bold ideas,” Afua Atta-Mensah, executive director of Community Voices Heard, told me. “Where is the battle cry of we’re going to get everyone in a room and save NYCHA?”

De Blasio has handled these accusations with his usual aplomb. When activists confronted him at his Park Slope gym about his administration’s lack of attention to the homeless, de Blasio answered: “I’m in the middle of a workout.” (De Blasio’s office declined a request for public comment.)

The mayor has also struggled to uphold his promises to reform the NYPD. Stop-and-frisks are down from a high of 685,000 in 2011 to just 10,861 in 2017, according to the Community Service Society, thanks in part to a judge’s ruling that the practice was unconstitutional. But racial disparities persist, and transparency and accountability within the police force remain elusive. According to a BuzzFeed report last year, hundreds of police officers remain in their jobs even after committing offenses serious enough to justify their firing. And brutal policing is still a ubiquitous fact of life for New Yorkers of color—just a few months ago, video circulated of NYPD officers wrenching a one-year-old son from the arms of his mother, Jazmine Headley, after someone called the cops on her for sitting on the floor of a food stamp office because there were no chairs available.

For many on the left, the disappointments with de Blasio came long before his blundering tour through Iowa in 2016. They point, first off, to the people he chose to run his administration. There was the appointment of Bill Bratton as police commissioner, who was infamous for popularizing the “broken windows” style of policing that fueled misdemeanor arrests of people of color. De Blasio also put Alicia Glen, a former Goldman Sachs executive, in charge of his housing program. “When we look at the current landscape of the Democratic Party, Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez would never do something like that,” said Westin of the New York Communities for Change. “From the very beginning of [de Blasio’s] administration he kind of signaled that he wasn’t actually going to be the progressive stalwart that he ran on.”

“With de Blasio, he’s progressive, within reach,” said Christina Greer, an associate professor of political science at Fordham University. “The very base that gives him his progressive credibility—which I would argue are people of color, primarily black Americans—when you sift through some of his policies, he’s actually not that progressive.”

It hasn’t helped de Blasio that the left has found new champions in politicians like Ocasio-Coretz and Sanders, both of whom seem more committed to the cause. There was perhaps no starker illustration of this contrast than when de Blasio and Cuomo finally buried the hatchet to engineer a backroom deal to bring an Amazon headquarters to Long Island City in Queens. Grassroots organizers, embittered City Council members, newly elected members of the Democratic state Senate, and Ocasio-Cortez herself all closed ranks against the plan. They cried foul over the billions of dollars in subsidies to the tech giant, the inevitable gentrification that would come with Amazon’s headquarters, and the failure of the politicians teeing up the deal to consult with the communities that would be most affected by these upheavals prior to signing on.

Amazon ended up withdrawing from Long Island City in response to the backlash from the left. At the eleventh hour, De Blasio tried to switch sides, criticizing Amazon’s decision to bail as “the 1 percent dictating to everyone else.” It was too little, too late. As Jose Cabrera, co-chair of the Queens branch of the Democratic Socialists of America, told The New York Times, “It seems that he’s a little bit torn on who he wants to be.”

For these and many other reasons, the people who know de Blasio best say he should sit 2020 out. When reporters recently noted that more than three-quarters of New Yorkers think a presidential run is a bad idea, he dryly responded, “I’m glad I could unify the people of New York City.”

But underneath that sardonic exterior, de Blasio seems undaunted. He has moved his communications director Mike Casca, who worked on Bernie Sanders’s 2016 presidential campaign, to his Fairness PAC, which funds national Democratic candidates as well as his own non-mayoral political activities. “I have spent a lot of time in dead last in many a poll in many a race,” he told The New York Times in January. “It’s not where you start. It’s where you end.”

The cruel irony for Bill de Blasio is that he may already be at the end of what has become a familiar cycle. He started with glowing press coverage, a fresh face with an alluring personal story to boot. He was then subject to the media’s unrelenting, unforgiving gaze, which exposed not a few blemishes. And he made some mistakes and bad compromises, as politicians are wont to do. Now Democratic voters have moved on to the next potential savior, practically begging de Blasio to take a seat. And the party’s seeming preemptive rejection of a de Blasio run raises a larger, more discomfiting question: Has governing experience in the age of Trump become a source of political liability rather than a basic qualification for office?

It’s undeniable that de Blasio has more accomplishments than many of his would-be presidential rivals—accomplishments that were secured despite the almost pathological animosity of a far more powerful figure in Governor Cuomo. Pete Buttigieg, for example, couldn’t even make it through the first round of votes in his bid to become Democratic National Committee chair two years ago. Yet he is now in the top three in the latest Iowa poll, ahead of both Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren. Buttigieg’s main selling points are that he would be the first openly gay presidential candidate and that he turned around a small Rust Belt city that had been in decline, but his record clearly doesn’t touch the breadth of de Blasio’s.

Then there’s Beto O’Rourke, a top contender despite having a paper-thin record—and what record he does have is decidedly centrist. As a U.S. representative, he voted with Trump nearly one-third of the time, including on issues ranging from immigration to taxes, despite representing a solidly Democratic district. He also received the second-most donations from the oil and gas industry of any Senate candidate in 2018—not unusual for a Texas Democrat, but problematic for a presidential candidate.

De Blasio, of course, would also be competing with candidates who do have formidable records: Elizabeth Warren, Sanders, potentially Joe Biden. Some voters may prefer O’Rourke’s middle-ground tendencies and Buttigieg’s cerebral earnestness and red-state bona fides; others may think Warren or Sanders are better representative of the left. But that can’t explain the veritable anti-buzz that surrounds a de Blasio run, while everyone else gets at least a turn in the warm glow of the national spotlight. If gaffes are such a problem, then why is Biden, a walking lawsuit waiting to happen, at or near the top of the polls?

Perhaps the real problem for de Blasio is that Donald Trump obliterated the idea that traditional qualifications—governing experience, policy expertise, deal-making—are a prerequisite for winning the presidency. Clinton, after all, had all those qualities in spades, and look what that did for her, not to mention the country. What matters, first and foremost, is that you win—which is why Democratic voters have become obsessed with that old chestnut, electability. And as Trump himself showed, sometimes the most electable politician is the one who has never done anything at all.

*A previous version of this article stated that Michael Bloomberg endorsed Christine Quinn in the 2013 mayoral race. He declined to officially endorse anyone, but publicly praised Quinn after she supported his controversial bid for a third term. We regret the error.