Perhaps the most surprising thing that Leonard Nimoy did with his time on earth, more surprising even than playing an iconic human-Vulcan space professional on television, was publishing a book called The Full Body Project. It’s a collection of black and white photographs of fat women in elegant formations, for example cavorting in a circle in imitation of Matisse’s La Danse. In her 2010 essay-collection-meets-memoir Shrill, Lindy West described coming across Nimoy’s book at a crucial moment in her personal development. “I was ragingly uncomfortable,” she wrote of the photographs. “I haven’t been having basement sex with the lights off all these years so you could go show what our belly buttons look like!”

But West also felt something “unclench deep inside.” Fat bodies, like hers, might not have to be treated like a secret. What if, she wondered, “I could just decide I was valuable and it would be true?”

Shrill is now a television show on Hulu starring Saturday Night Live’s Aidy Bryant. Bryant plays a fictionalized version of West, named Annie, who resembles West at the moment when Spock was helping her break out of society’s anti-fat mind-prison. She works at The Weekly Thorn—a stand-in for the Seattle alt-weekly The Stranger, where West wrote before moving to Jezebel—and finds empowerment through writing. Her boss, an avatar for the sex advice columnist Dan Savage, is an anti-obesity evangelist whom she takes down in an essay titled “Hello, I Am Fat.” It’s a real essay, appearing in edited form in Shrill.

Times have changed, and Shrill the television show is proof. The first scene shows Bryant looking hot, in cute underwear, while fat. The first episode shows Bryant calmly getting an abortion, correcting two popular misconceptions—that abortions are traumatic and that fat women don’t have sex—at once. These are simply not things that we see on television, and in that respect Shrill is revolutionary.

The problem with the series is that it lacks tension. There is little sense of what, exactly, is propelling Annie forward into her new political consciousness. Yes, we see her bullied by non-fat people and browbeaten by mediocre men, until she simply reaches a frustration point that breaks through into revelation. But that is not quite how West arrived at her own tentative salvation. Something has been lost in translation: specifically, the story of how culture changed around the turn of the millennium, and what West had to do with it.

It’s easy to forget how extraordinarily disrespectful American culture was toward fat people in the last few decades of the twentieth century. That’s an enormous generalization, of course. Fatphobia continues to thrive in the hearts of teen girls and on gross websites alike. People dieted before skinny movie stars were invented, and will continue to do so. But one could argue that “body negativity,” aka compulsory thinness, was a phenomenon that spread through mass media in the 1960s and 1970s and reached its apotheosis, just before it died, in the 2000s.

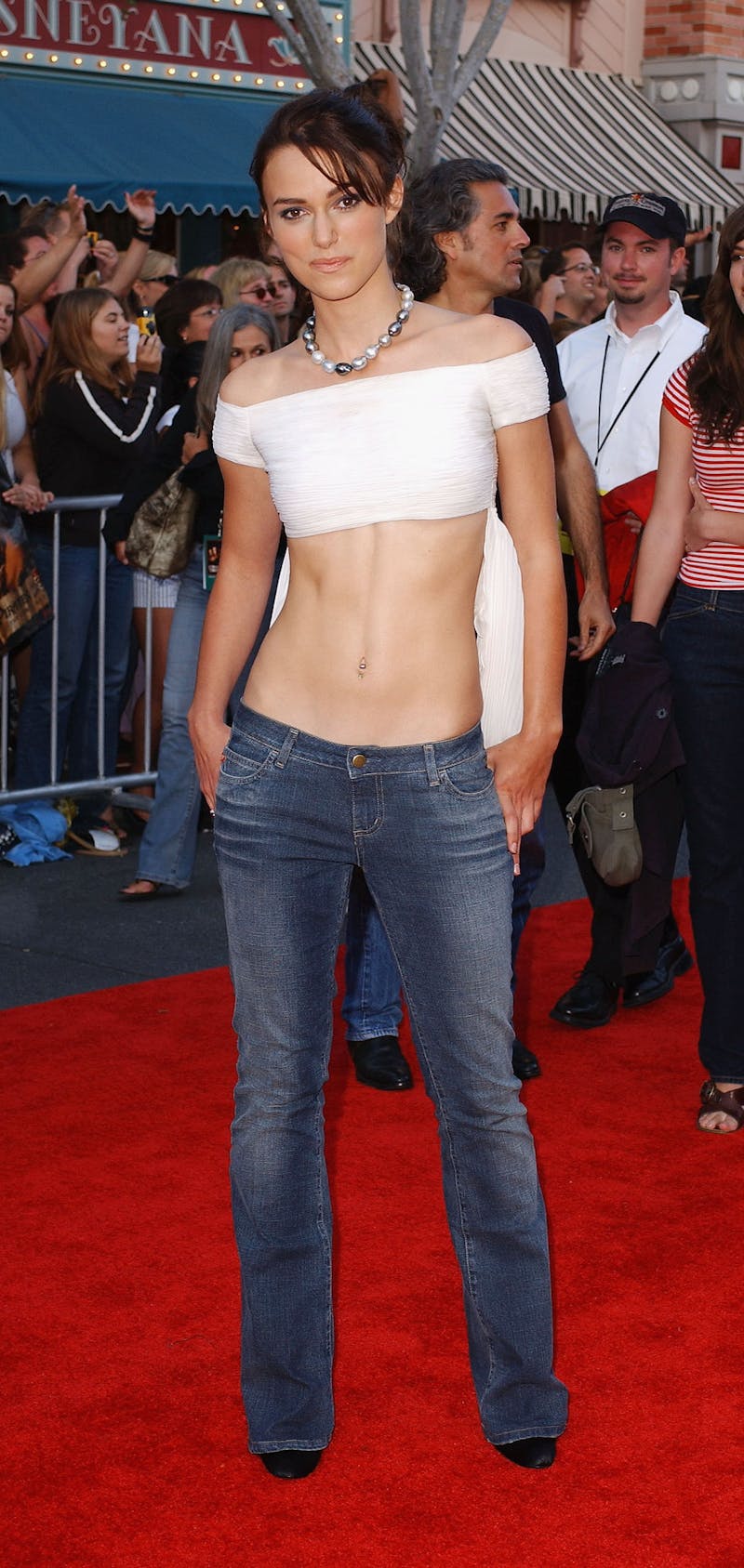

I turned 13 in late 2000 AD, and it’s my biased opinion that this was a singularly bad time to be a young girl. The 1990s had drawn to a close in the shadow of Britney and her 1000-crunches-per-diem abs, and we still had The O.C. and The Simple Life and America’s Next Top Model ahead of us. Every celebrity seemed to be a white Californian doppelgänger, and they were all thin to the point of absurdity, which was obvious because at the time jeans were made to be suspended, bridge-like, between the points of one’s hipbones. Perhaps you remember the outfit Keira Knightley wore to the 2003 premiere of Pirates of the Caribbean? Low-rise jeans, an expanse of bony torso, and a piece of white fabric wrapped around her chest. Those photos should be in the Smithsonian.

They ended up, however, being the nightmare fungus of pro–eating disorder internet culture. There were a lot of these websites at the time, and they posted “thinspiration” images of celebrities for aspiring anorexics to drool over. Certain pictures cropped up over and over again: Kate Moss leaning against a wall with a string of lights draped over her, Kate Moss in the Eternity advertisements, Kate Moss doing anything, really. This trend continues on Instagram today, of course. But there was a sense back then that the “pro-ana” websites were in lockstep with mainstream screen culture. This was Beauty, and television proved it.

This championing of the super-thin is no longer modern, chic, or interesting. We are not in the early phase of body positivity any more, and plus-size models are no longer novel. Brands like Thinx and Aerie now show diverse bodies in ad campaigns, and they don’t do it out of the goodness of their hearts: They do it because that’s what sells. Something happened between 2006, when Nicole Ritchie was hugely famous just for being skinny, and 2016, when Lindy West published Shrill, the first book about fat acceptance to really sell well.

It’s hard to pin down exactly what changed, and no single thinker is at the root of it, but in that decade a huge volume of feminist writing appeared online. LiveJournal reached 5 million accounts in 2004; Jezebel started publishing in 2007; xoJane ran from 2011 to 2016. It’s very hard to find records of the earliest plus-size fashion bloggers, because so much is simply gone from the internet, but many people talk about the invention of the “fatosphere” in the mid-2000s as the third wave of the fat acceptance movement. Writers like Marianne Kirby (The Rotund) and Kate Harding (Shapely Prose) made phrases like “health at every size” familiar. Fashion for fat people took off in a huge way, community-style: I remember marveling at the #fatshion tag on Tumblr around 2008, simply astonished to see such beautiful bodies in such beautiful outfits.

Within that movement, Lindy West emerged. To the show’s credit, Shrill shows how her essay “Hello, I Am Fat” broke out online, and the vitriol it unleashed among trolls the world over. (West is probably most famous for her trolls, in fact, after recording a confrontation with one for a popular episode of This American Life.) The early internet writing of West can be divided into three major projects, which she herself describes in her book:

Decisive victories are rare in the culture wars, and the fact that I can count three in my relatively short career—three tangible cultural shifts to which I was lucky enough to contribute—is what keeps me in this job. There’s Costolo and the trolls, of course. Then, rape jokes. Comedians are more cautious now, whether they like it or not, while only the most credulous fool or contrarian liar would argue that comedy has no misogyny problem. “Hello, I Am Fat” chipped away at the notion that you can “help” fat people by mocking and shaming us. We talk about fatness differently now than we did five years ago—fat people are no longer safe targets—and I hope I did my part.

The “rape joke” work is worthy of its own book. In 2013, West campaigned against misogyny in comedy, particularly jokes about rape. The effort culminated in a televised debate between her and comic Jim Norton, which is a painful thing to watch, when it is now so obvious who is right and who is wrong.

So, there is Lindy West the shy young person, who now appears in the TV series Shrill. There is Lindy West the beautiful and confident celebrity writer, all over the internet looking gorgeous in her wedding dress. And then there is Lindy West the cultural institution—the blogger who best exemplifies the social consciousness turn in online writing in the early 21st century. One of these Lindy Wests matters more than the others, and it’s not the one you see on Hulu.

A big part of representing fat women on TV involves busting myths about their desirability. In her book, West quotes a line from the actress-comedian Rachel Dratch’s memoir: “I am offered solely the parts that I like to refer to as The Unfuckables. In reality, if you saw me walking down the street, you wouldn’t point at me and recoil and throw up and hide behind a shrub.” This line is reminiscent of Girls star Lena Dunham’s response to critics who thought her on-screen romance with the hunky Patrick Wilson was “unrealistic.” As Dunham noted, women who look like her bang hot men all the time. “Really?” she said. “Can you not imagine a world in which a girl who’s sexually down for anything and oddly gregarious pulls a guy out of his shell for two days?” Like West’s debate, that episode of Girls aired in 2013.

Casting fat women as “The Unfuckables” does not reflect the actual experiences of fat women in the world. It just reflects the way that movies and television are produced—the same ideology that made mass media so hellish for tween girls at the turn of the century.

Which brings us back to Shrill, and its radical potential. If there’s one target it hits right at the bullseye, it’s the taboo around desiring fat women in public. Bryant looks good, all the time. In the best episode, where Annie attends a pool party full of other fat women, Shrill shows beauty and abundance. It’s about spontaneous revelation, the mists of Hollywood delusion suddenly clearing to show a paradise of fat joy. If the show is to be a charming meander through the life of one fat woman realizing that she is allowed to be happy, then it is a total success.

Shrill should also be praised for discarding the mid-2000s vibe that suffuses West’s book. It’s an unfortunate fact of history that West’s is the kind of voice that was popular in 2010 but now reads as a bit corny. (Sample sentence: “More like vagin-UUUUUUUGGGHHHHHHHH.”) We have come a long way in terms of “voiciness” in online writing, and the era of typing in all caps in between Sherlock references are happily long gone, along with those ModCloth sidebar ads.

But despite any aesthetic disagreements I might have with Shrill the book, it is clear that we are still grappling with the ideas of that era. The danger now is that the fat acceptance movement is being co-opted by advertising. Women no longer write politically controversial blogs; instead, they hold sponsored objects in their Instagram posts about body positivity (Bitch published an exceptional dissection of this phenomenon in 2017). Shrill gives us a rare opportunity to really think about what changed in our minds and hearts, and to make sure that sea change stays permanent. But Lindy West is the hero of that story, not Annie.