Sometimes you have a bad year. That’s always been the reality of being a farmer or rancher. The business of growing crops and raising animals for profit requires two crucial elements for success that are out of farmers’ control: good weather, and good government policy. No one enters the agricultural profession thinking that every season is going to be successful.

But farmers and ranchers, particularly in the Midwest, have had more than just a bad year or two. Wisconsin’s dairy farms are in crisis, having lost about half of their net income between 2011 and 2018. They’re now shutting down at a record rate, due to low milk prices, overproduction, and President Donald Trump’s trade war with China and Mexico. That war has also caused billions in combined losses to Iowa’s soybean, corn, and hog industries. Nebraska farmers lost between $700 million and $1 billion in income last year. In Minnesota, farmer income fell 8 percent, making 2018 the worst year since the farm crisis of the 1980s.

And now the Midwest has been hit with historic, devastating floods. Excessive snow melt and rainfall, notably the “bomb cyclone” two weeks ago, have caused vast fields of corn, soy, and other crops to be washed away. Countless hogs, calves, and chickens have been killed. Iowa is estimating $1.6 billion in losses, Nebraska $1.3 billion, but the overall damage is hard to calculate because the floodwaters haven’t receded. It’s likely they’ll get worse. “The extensive flooding we’ve seen in the past two weeks will continue through May and become more dire,” Ed Clark, director of NOAA’s National Water Center, said in a statement to Vox.

While bad luck is indeed normal for the farming business, this season’s crisis is neither normal nor a matter of luck. The volatile weather is part of a larger pattern of human-caused climate change, and the Trump administration is deliberately prioritizing industrial-scale agriculture; both are making it harder for small and midsized family farms to stay afloat. If these trends become the new normal, local family farming as we know it will die.

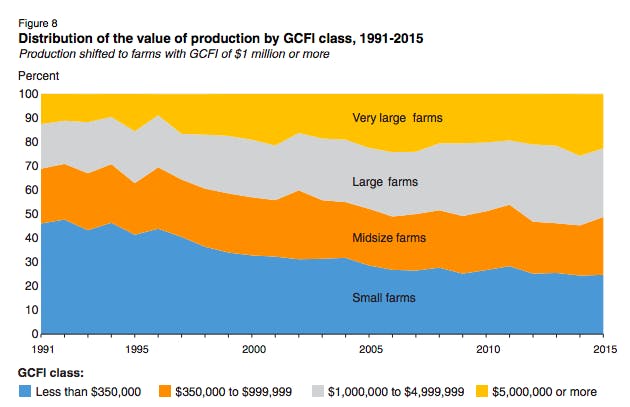

In 1982, America was home to about 2.2 million farms. That number hasn’t changed much; according to the USDA, America now has about 2.1 million farms. But today’s farms are a lot bigger than they used to be. In 1987, only 15 percent of farms had 2,000 acres or more of cropland. By 2012, 36 percent did. The USDA credits the rise of big farms to consolidation: small and midsize farms combining to form larger operations, or getting bought out by such operations.

This often happens because smaller farms aren’t making enough money to survive on their own, said Joe Schroeder, a senior farm advocate for the nonprofit

Farm Aid. And one of the many reasons why they’re not making enough money is that catastrophic weather—like this year’s flooding—keep knocking them when they’re already down. “Flooding like this always accelerates consolidations,” Schroeder said. “It hurts the poor folks and it helps the rich folks.”

Consolidation has been underway for some time, and isn’t solely related to weather; agricultural policy increasingly favors large operations with lots of resources, Schroeder said. But weather events like extreme flooding “puts [consolidation] into fast-motion and intensifies it,” he added. “It’s like pouring a gasoline on a fire.”

Such weather is becoming more common. According to the National Climate Assessment, heavy-rain events have risen 37 percent in the Midwest since the 1950s, and the magnitude of river floods is steadily increasing. The region also has been hit with a series of anomalous disasters that tend to affect farmers and ranchers more dramatically: In 2011, eleven of the country’s 14 weather-related disasters with damages exceeding $1 billion were in the Midwest. The assessment says that climate change is likely to “increasingly disrupt” American farming with extreme heat, drought, wildfires, and heavy downpours. These effects vary with the season. As the tech news site Seeker reported in January, “Kansas is likely to see earlier spring-like weather, more heat waves, longer gaps between rainfall, and heavier downpours when the rain does arrive.” And in the summer, swings between rainfall “often coincide with heat waves that can damage crops.”

While the effects of climate change may vary from season to season and place to place, the result is the same: Small and midsize farmers are more worried than ever about their future, and feel their only choices are to quit or consolidate. Schroeder, who frequently answers calls for Farm Aid’s farmer help hotline, says he hears it almost every day. “It’s people on the kind of continuum where they no longer have any control over their own demise,” he said. “They’re just participating in a way that causes the least destruction, or gives them a little more time.”

Senator Elizabeth Warren, who is running for president, unveiled a plan on Wednesday to help these farmers, promising to “tackle consolidation in the agriculture and farming sector head on and break the stranglehold a handful of companies have over the market.” Her plan may help ease the crisis, but ultimately, it will require tackling the much bigger problem of climate change. “Maybe these floods are the beginning of a washed-out grain belt that no longer produces grain,” Schroeder said.

This is the apocalyptic future that America is facing. It’s surely a long way off. But year to year, season to season, small family farmers are glimpsing that future on their own land today. They’re facing their own personal apocalypses.