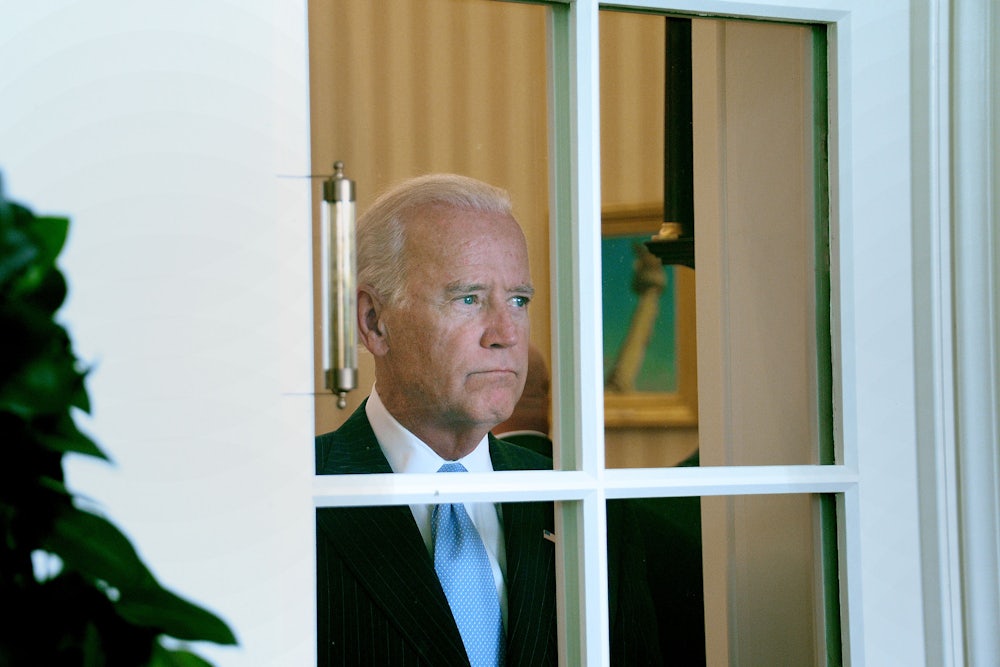

Joe Biden knows what you’re thinking. He has seen the stories, too.

He knows he’s too old: 76 years old today, and 78 on Inauguration Day, 2021. He knows that, as a senator representing Delaware for nearly half a century, his extensive ties to the banking, credit, and financial industries are liabilities in an increasingly populist Democratic Party. He knows that his treatment of Anita Hill during Clarence Thomas’s confirmation hearings, and the dozens of photographs of him being handsy with women over the years, are being scrutinized in a new light. And he knows he was on the wrong side of the crime debate.

Biden, who has yet to announce his candidacy for president, reportedly is weighing two solutions to the problem of his unsavory record. One is to pledge to leave office in 2021, at age 82. The other is to name Stacey Abrams, a black woman 31 years his junior, as his running mate early in the race. Such a “big play,” in the New York Times’ words, “would send a signal about the seriousness of the election, and could potentially appeal to both liberal activists and general-election voters who are eager to chart the safest route toward defeating President Trump.”

But the fact that Biden is even considering these moves only underscores his innumerable flaws, rather than addressing them.

It’s easy to see the appeal of a one-and-done presidency. Biden’s age, like that of the 77-year-old Bernie Sanders, undoubtedly would be a concern for some Americans, given the erratic and seemingly cognitively impaired septuagenarian currently in the White House. Promising to serve only one term could reassure voters concerned about the fact that Biden (and, for that matter Sanders) would become America’s first octogenarian president before the end of his second year in office.

And teaming up with Abrams, who energized the party during an unsuccessful bid for governor of Georgia, could show he has evolved on race and women and potentially inoculate himself from further criticism. It would be a salve, as New York’s Jonathan Chait argued, for “Biden’s cringe-inducing and sometimes ghastly history of retrograde positions on segregation and criminal justice,” would energize Democratic voters, and “would make Biden’s race feel more serious.”

But it’s worth taking a moment to revisit that cringe-inducing and sometimes ghastly history. Biden, as Ryan Cooper wrote in The Week, was one of the Democrats who “pushed the party away from Civil Rights.” Biden embraced anti-integration measures early in his career in the Senate, becoming what Politico termed “a leading anti-busing crusader” in the 1970s. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Biden was one of the most vehement anti-crime crusaders in the Senate, pushing increasingly draconian punishments. Biden “wasn’t trying to compromise with the Republicans” on crime, Ta-Nehisi Coates told New York magazine recently, but “to get to the right of Republicans.”

Biden did so proudly. “Quite frankly, the president’s plan is not tough enough, bold enough, or imaginative enough to meet the crisis at hand,” he said in 1989 about a crime bill being pushed by President George H. W. Bush. “In a nutshell, the president’s plan does not include enough police officers to catch the violent thugs, enough prosecutors to convict them, enough judges to sentence them, or enough prison cells to put them away for a long time.” In the Senate, Biden backed mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenders, civil forfeiture, and the death penalty. He bragged that one Democrat-backed crime bill in 1992 did “everything but hang people for jaywalking”; two years later he would be a principal author of the 1994 crime bill that exacerbated mass incarceration.

“There’s a tendency now to talk about Joe Biden as the sort of affable if inappropriate uncle, as loudmouth and silly,” sociologist Naomi Murakawa told the Marshall Project in 2015. “But he’s actually done really deeply disturbing, dangerous reforms that have made the criminal justice system more lethal and just bigger.” Biden recently apologized for this stain on his record, saying “I haven’t always been right. I know we haven’t always gotten things right, but I’ve always tried.”

Biden also recently suggested that he owes an apology to Anita Hill for his handling, as chair of the Judiciary Committee, of her accusations of sexual harassment against Clarence Thomas. “Anita Hill was vilified when she came forward by a lot of my colleagues, character assassination. I wish I could’ve done more to prevent those questions and the way they asked them,” he said on the Today show last year. But Biden, as the Boston Globe’s Joan Vennochi noted, “also posed questions designed to humiliate her” during her testimony. By failing to call favorable witnesses or solicit affidavits from experts on sexual harassment, Biden was as responsible for Hill’s “character assassination” and Thomas’s place on the Supreme Court as anyone. “He did everything to make it be good for Thomas and to slant it against her,” Georgetown University law professor Susan Deller Ross observed to the Times in 2008.

Biden may feel he owes Hill an apology, but he hasn’t actually given it. “It’s become sort of a running joke in the household when someone rings the doorbell and we’re not expecting company,” Hill told Elle last fall. “‘Oh,’ we say. ‘Is that Joe Biden coming to apologize?’”

These are just a few of the myriad sins that Biden and his advisers hope to neutralize with a novel campaign strategy. But these moves would likely backfire. Announcing that he will only serve one term will make Biden seem weak and not up for the job, reminding voters yet again that he would be by far the oldest president ever. Announcing a running mate nearly two years before an election, as an attempt to cover up past failings, will only draw more attention to them. And if you’re a career-long politician who can’t run on your record, then why are you running at all?