There’s a museum in East Jakarta that enshrines a toxic historical fantasy. Of course, all nations whitewash their bloody histories in the course of creating a heroic narrative about their stirring rise to power and global influence. But Indonesia’s official memorial to the wave of political massacres that claimed the lives of at least 500,000 civilians in 1965 while laying the groundwork for the 32-year reign of the military strongman Suharto is an entirely different study in nationalist mythology. It’s a through-the-looking-glass distortion of nearly every important facet of the recent political history of the world’s fourth-most-populous nation.

There is, first of all, the name of the place: the Communist Betrayal Museum. According to all organs of official consensus in post-Suharto Indonesia, the tragedy of 1965 wasn’t so much the wholesale military slaughter of half a million natives of this vast island archipelago. No, as the official version would have it, the political movement that authored the massacres also comprised their most notable victims.

It’s a decidedly brazen narrative approach to absorbing the trauma of a mass killing in an emerging democratic political culture. The sick audacity of the museum’s mission is exhibited in diorama displays devoted to the seven military officials killed in what the exhibit describes as an abortive Communist coup launched in October 1965. There’s nothing remotely resembling, say, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s chilling displays of shoes, watches, and other personal possessions of the six million Jewish victims of the Nazi genocide.

In place of any such symbol of healing remembrance, there are rather slapdash wax facsimiles of the seven military officers—which stand out in striking contrast to Indonesia’s rich tradition of expressive, detailed, and carefully rendered figurative sculpture—who were interred at the museum’s site. The installation goes on to suggest that the martyred heroes were tortured by the vicious leaders of the Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI)—killers allied with the short-lived nonaligned socialist presidency of Sukarno, a pivotal figure in Indonesian history conspicuously denied a place of honor in the Communist Betrayal Museum.

Even this origin story is distorted and misleading, it’s important to note. There’s no evidence, based on the autopsies of the seven killed officers, that they had ever been tortured, for example. What’s more, some independent Indonesian historians believe that even if PKI operatives carried out the killings, only a tiny number of party officials—the chairman and agents attached to a small covert bureau he controlled—knew about the plan. When the killings were carried out, even senior members of the PKI Politburo were shocked when they got word of them.

The museum holds 34 dioramas portraying brutal acts the PKI allegedly committed. The first dates to 1948 and depicts “Victims of the Ferocity of the Revolt of the PKI.” Another shows Suharto “at excavation of victims of the malignancy of the PKI rebellion in the Crocodile Pit”—the name of the Jakarta neighborhood where the museum is located.

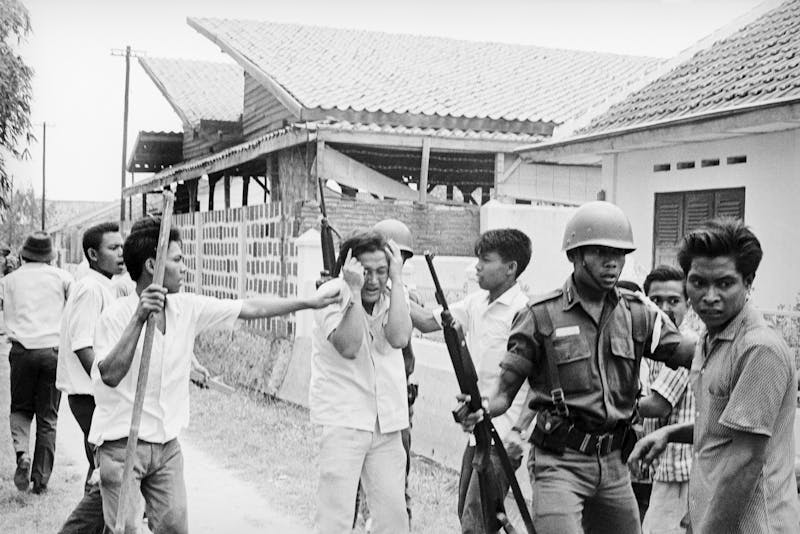

One can’t help but suspect that this agitprop perversion of Indonesian history obsessively dwells on the myth of rampant Communist torture as a form of psychic compensation. The 1965 massacres, measured by the speed by which they metastasized and their number of fatalities, mark one of the most brutal and unfathomable reigns of political terror in history.

The Indonesian military and Islamic groups whipped up hatred through political gatherings and propaganda broadcasts, and victims were hacked to pieces, mutilated, and decapitated. Women and girls were targeted for killing, and many were raped. A striking collateral casualty—and one that’s extremely consequential for the forces now holding autocratic power in Indonesia’s extraordinarily unequal and investor-friendly manufacturing economy—was the nation’s vibrant labor movement and other civil-society groups promoting a variety of leftist causes, from agrarian reform to factory-level democracy.

Jeffrey Winters, a political scientist at Northwestern University who has written about global oligarchy, is a leading expert on Indonesia and the 1965 massacres. (Many of the leading experts are foreign because relatively few Indonesians write about the massacres, and the key archives are located abroad, with many in the United States.) When I spoke with Winters on my return from Indonesia, he explained that the vast national memory hole engulfing the 1965 massacres was more than a set of convenient state fictions; it was part of Indonesia’s induction into the now-infamous race-to-the-wage bottom in the supply chain of globalized manufacturing.

“The Massacre Premium is the premium that has accrued to capital because Indonesian workers have never been able to organize and fight for their rights ever since the events,” he told me. “You can’t precisely quantify it, but it’s billions and billions of dollars. Since 1965, anyone trying to position themselves as a powerful, genuine voice for workers has risked their life.”

Or to put things another way: the Communist Betrayal Museum supplies a blueprint of sorts for the manipulation of historical memory in the service of fomenting workers’ fear and submission. Go anyplace where Indonesian workers are ransacked of their wages, their job security, their collective bargaining rights, and their freedom to protest their treatment, and you can see the long shadow of the 1965 trauma—and the compound interest still being reaped from the Massacre Premium.

Suharto took full control of Indonesia in March 1967, when the elected president, Sukarno, was officially deposed. Suharto ruled until 1998, when riots forced him to resign, and became one of the United States’ key allies in Southeast Asia. He stole roughly $30 billion during his years in power, and his one-party dictatorship killed many people—no one will ever know how many—and threw untold numbers of supposed enemies of his regime in prison.

Suharto held power the same way he won it—via a concerted campaign of domestic terror and the violent suppression of dissent. Communism was made illegal, and it remains so today. The strongman cult of personality he presided over—known in modernizing coup-speak as the “New Order”—continues to shape the dismal state of the political economy in contemporary Indonesia. That’s especially the case when it comes to the country’s pivotal role in providing readily exploited and discarded labor on the cheap for the lords of the feverishly globalizing garment and apparel industries.

Indonesia is today a democracy, technically, but that term cannot accurately describe the country, which is riven by economic inequalities. Members of the old Islamist-military oligarchic elite rotate back and forth in power. The fear generated by the slaughter hangs over the country today, particularly in the struggle to introduce a measure of justice and equity in the vastly exploitative garment industry.

As Winters points out, the risk to union organizers and activists is still palpable, even though the country elected a president in 2014, Joko Widodo, who is a reasonably moderate and reform-minded civilian leader, at least by Indonesia’s traditional standards. The problem is that the military has severely constrained him from doing anything remotely decent for his people, and it and his other enemies routinely and absurdly label him a Communist—a tactic that functions as another sort of Massacre Premium, compelling Widodo to mind his every move in the face of possible military resistance and behave as the army’s leaders want him to. “Under Suharto, labor was completely suppressed, and the brutality of the military-intelligence regime sometimes makes people think that labor was only weak because of that,” Winters said. “But labor is still weak today, and there is still the same level of fear. It’s not the fear that the Suharto regime will knock on your door and take you away, it’s the fear of being labeled a Communist. It’s in the mind and internalized.”

You can indeed still feel the longer-term damage wrought by Suharto and his military enablers throughout today’s Indonesia. His legacy adds up to much more than fear, corruption, and oligarchic control of the political system. The dictator also bequeathed to successive generations of Indonesian workers a casualized low-wage economy, in which apparel has been and remains a key industry, though one in relative decline as other sectors, like electronics manufacturing and the auto parts industry, emerge.

Workers’ salaries in some regions of Indonesia are among the lowest in the world. Recently, the chairman of the Indonesian Textile Association, Ade Sudrajat, said he feared that global apparel brands—including those from the United States, which is the major market for Indonesian apparel exports—would move to Ethiopia, where wages are even lower than in Indonesia. Ethiopia has been destabilized by civil war and rule by kleptocratic strongmen for much of its modern history, and now operates as a punishingly low-wage manufacturing economy under the U.S.-backed regime of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. “Some of our members are actually already invested in Ethiopia,” Sudrajat told The Jakarta Post.

Of course, salaries for apparel workers are poor everywhere. But as Scott Nova of the Worker Rights Consortium (WRC), which advocates for apparel workers around the globe, told me, “The common denominator is that foreign apparel firms avail themselves of poverty wages wherever they are available. Whether there’s a democracy or dictatorship doesn’t make any difference for them.”

Even worse, apparel workers who get paid terribly to begin with are routinely victims of wage theft, and Indonesia is the global epicenter for this practice. Wage-theft regimes operate essentially by disbursing the marginal gains won by factory owners and brand contractors into the coffers of far-flung investors perched atop the global financial elite via a virtually silent and unregulated mode of managerial larceny.

As a result, Indonesian apparel workers have been cheated out of hundreds of millions of dollars over the past two decades or so as they work in sweatshops that subcontract their labor out to a wide array of well-known global brands. One sprawling brand-subcontractor in Indonesia is PVH Corp., which manages, its web site boasts, “a diversified portfolio of brands—including CALVIN KLEIN, TOMMY HILFIGER, Van Heusen, IZOD, ARROW, Speedo, Warner’s, Olga, Geoffrey Beene and True&Co.” Among American brands, PVH Corp. has been particularly unresponsive to requests from workers to help pay their stolen severance money.

Wage theft happens everywhere under the new globalized conditions of factory closure. When sweatshop operations migrate and disband in Indonesia and the global South, they will typically refuse to pay workers what they’re owed in salaries and legally mandated severance. “It’s effectively become standard operating procedure for many factory owners,” Nova said. “The cost reduction achieved by not funding severance liability is baked into the garment pricing structure: The brands aren’t paying enough to adequately cover severance benefits. When these suppliers shutter a factory—after brands send their business elsewhere—grand larceny is part of the process.”

Nova said that there’s no easy way to calculate how many Indonesian workers are victims of wage theft, but he conservatively estimates the number as at least half a million. “We learn about new cases every year,” he explained, “2,000 workers at this factory, 5,000 at that one. And the cases we’re able to document are a fraction of the total.”

The factories know they can get away with wage theft without any serious legal or financial consequences, because governments, journalists, and other watchdog concerns simply don’t care—and the American and European brands that buy from these factories are entirely complicit in the theft. In the wake of an earlier wave of protests about sweatshop conditions in the global garment industry, the major players in the sector convened what was essentially an astroturf array of oversight bodies that nominally certify fair labor practices in factories owned and run by international subcontractors. Two of these groups, the Fair Labor Association (FLA) and the Fair Wear Foundation (FWF), promulgate a code of conduct for participating companies requiring that compensation paid to employees of their supplier factories “shall meet at least legal or industry minimum standards,” as the FWF says. But both groups have done very nearly nothing to ensure that these provisions are enforced in the economy of the global garment sweatshop industry. Despite concerted but inevitably insufficient pressure from the WRC and other watchdog groups, the brands have almost all refused to compensate workers when they shutter their overseas manufacturing facilities.

While the overall scale of wage theft in Indonesia is forbiddingly hard to establish, there are a few edifying case studies that the WRC and other industry critics have documented in some detail. Perhaps the most bracing one involves the overseas exploits of Stephen Schwarzman, who heads up the giant hedge fund Blackstone Group. Until July 2017, Blackstone controlled the garment concern Jack Wolfskin, which bought clothing at two factories owned by an Indonesian firm, Jaba Garmindo, in industrial zones around Java. The factories shut down without notice and laid off 4,000 workers. Per the traditional shakedown model of garment-sector labor relations, Jaba Garmindo promptly stopped paying wages owed to the factory’s former workforce, and withheld all severance from them as well. (A representative for Wolfskin denied that the garment line had withheld back wages or severance from fired factory workers; a TNR request for a response from Schwarzman’s fund went unanswered at press time.)

The Jaba Garmindo workers were collectively due a piddling amount—about $10.8 million, or about half of what Schwarzman reportedly spent on his 70th birthday party in Palm Beach in 2017. The event featured live camels, trapeze artists, a performance by Gwen Stefani, and, in a particularly gruesome irony, a deluxe assortment of Asian-themed decorations. Schwarzman’s good friend, President Donald Trump, didn’t attend the party, but many key members of Trump’s inner circle did, including first daughter Ivanka Trump, who licensed an apparel factory about a four-hour drive from Jakarta. (The Ivanka Trump clothing line shut down in 2018—not long after a story by Guardian writer Krithika Varagur reported on “employees speaking of being paid so little they cannot live with their children, anti-union intimidation and women being offered a bonus if they don’t take time off while menstruating.... There are claims of impossibly high production targets and sporadically compensated overtime.”)

Schwarzman’s Blackstone Group now controls more than $472 billion of assets under its management, making Schwarzman one of the richest people on the planet, with estimated wealth of more than $13 billion.

And just as Ivanka Trump happily leveraged her global brand on the backs of Indonesian garment workers, so is Stephen Schwarzman parlaying his hedge-fund riches into an influential seat among the new Trumpian centers of power. Schwarzman did not endorse Trump in 2016, but he donated more than $4 million to Republican PACs during that election cycle. He also contributed $250,000 to Trump’s inauguration, and watched midterm election returns with Trump and other big-ticket conservative donors like Sheldon Adelson.

Blackstone’s real-estate division also lent $312 million to Kushner Companies—the assemblage of holding concerns controlled by Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law—along with the Brooklyn arm of Kushner’s real-estate empire. Schwarzman also served as chairman of Trump’s Strategic and Policy Forum. That advisory group met only a few times, and a number of high-ranking CEOs resigned in protest after white nationalists rioted in Charlottesville in 2017 and Trump offered them support. Schwarzman, however, stood by Trump and only left the advisory council when it was quietly disbanded.

And Schwarzman’s grasp of the historical logic of world genocide does seem decidedly shaky. In 2010, when President Barack Obama raised the possibility of revoking the carried interest tax loophole that is only available to one-percenters, Schwarzman rallied to the charge with an ill-considered historical analogy: “It’s like when Hitler invaded Poland in 1939,” he said to a room of fellow investors. Schwarzman is estimated to have saved $100 million in federal income taxes per year from 2013 to 2014, thanks to the carried interest loophole.

Back in Indonesia, meanwhile, former workers at one of the Jaba Garmindo factories—who are owed on average about $2,500, a sum larger than they are otherwise likely to see at any one time in their lives—have been fighting desperately and without success to get the factory owners and brands who laid them off to pay them the full sum that they’re owed. Schwarzman could write a personal check for $10.8 million and resolve the Jaba Garmindo crisis without even noticing the difference in his cash reserves, but, following the lead of nearly every other foreign investor in the country’s garment sector, he has refused to do so.

It would be a mistake to believe that the historical amnesia that lurks behind Indonesia’s wage-theft regime was exclusively self-administered. Quite the contrary: American diplomatic officials and shapers of elite opinion were gleefully complicit in the construction of the Massacre Premium.

Nineteen sixty-five was, after all, close to the peak of Cold War superpower hostilities, and nonaligned socialist countries like Indonesia were, in the policy narratives peddled by American military-industrial officialdom, among the gravest threats to First World freedom then going.

Indeed, if anything, the United States was perhaps even more terrified than the Indonesian military that Sukarno’s nonaligned socialist government would settle into a long-term hold on power in a part of the world that Western defense intellectuals viewed as the premier testing ground for the so-called domino theory. Under this influential but never-demonstrated article of diplomatic faith, a long series of unstable former colonial powers were supposedly poised to come under Soviet influence in one disastrous fell swoop.

Indonesia was arguably the biggest domino of all—it was among the world’s most populous countries and, under Sukarno, had a great deal of international influence without ever serving as a U.S. puppet regime. Meanwhile, American involvement in Vietnam was deepening—the Pentagon had begun to aid the French in the early 1950s, until the Viet Minh inflicted a crippling and fatal blow to French troops at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, forcing French withdrawal—and things were already taking a turn for the worse.

As a result of all these trends, the deans of the American Cold War establishment agreed that, should the PKI prevail in a popular national election, the fallout would be disastrous for America and its First World allies. So the United States swiftly set to work to join forces with the Indonesian military and anti-Communist Islamists to exterminate the PKI and its supporters.

Direct U.S. support for the massacres is by now a well-established fact. In 2017 the nonprofit National Security Archive, along with the National Declassification Center, published extensive diplomatic cables covering “that dark period,” as an excellent story by Vincent Bevins in The Atlantic said at the time. “Untold numbers were tortured, raped, and killed simply for being accused of being communist,” Bevins wrote. “Simply for their political beliefs, they were subjected to mass slaughter. Across the country, one by one, Indonesians were shot, stabbed, decapitated or thrown off cliffs into rivers to be washed into the ocean,” Bevins observed in a piece for The Washington Post.

And there was this utterly astonishing admission published in The Atlantic:

In 1990, a U.S. embassy staff member admitted he handed over a list of communists to the Indonesian military as the terror was under way. “It really was a big help to the army,” [said] Robert J. Martens, a former member of the embassy’s political section, told The Washington Post. “They probably killed a lot of people, and I probably have a lot of blood on my hands, but that’s not all bad.”

It would be nice to think critical lessons about the abuse of American power abroad might arise from such devastating findings—but there’s no basis to sustain that feeble hope. Indeed, even when Suharto died at 86 of heart, lung, and kidney problems in 2008—ten years after he was driven from office by massive protests and 43 years after the massacres began—the American press was still in militant retreat from political reality. The New York Times published a revoltingly misleading obituary that wanly pronounced that Suharto’s “rule had not been without accomplishment; he led Indonesia to stability and nurtured economic growth.” Yes, it was true that “these successes were ultimately overshadowed by pervasive and large-scale corruption; repressive, militarized rule; and a convulsion of mass bloodletting that took at least 500,000 lives when Suharto seized power in the late-1960s,” but why dwell on the negative?

This piece of agitprop from the American paper of record might have been a worthy addition to the Museum of Communist Betrayal. The Times, by seeming force of institutional habit, covered up the fact that Suharto was drenched in blood. “Suharto’s precise role in the violence is not clear,” the obit continued, in defiance of the by now well-documented historical record. “He managed to keep his name from being directly attached to it.”

Such willed ignorance of political fact only bolsters the socioeconomic climate in which wage theft proliferates. The Indonesian government considers the export-oriented textile and apparel industry to be “strategic,” and it generates about 1 percent of the country’s annual GDP—or 7 percent of Indonesia’s export revenue. There are officially 2.2 million apparel workers on the line in Indonesia, but only a small percentage are unionized. And that 2.2 million figure is well short of the likely actual head count, since factory employees have been increasingly transformed into nonunion home workers, who get paid even worse than their sweatshop-based counterparts.

There was a burst of energy in democracy and union organizing after Suharto’s fall in 1998, and, largely thanks to that short-lived movement, Indonesia’s labor laws are better than those in most countries in the region. For example, severance pay for laid-off Indonesian workers is well above the standard in neighboring countries. Yet these comparatively generous legal safeguards are rarely observed in the breach, which is why Indonesian workers are the globe’s biggest victims of wage theft.

What’s more, as Bent Gehrt, the Southeast Asia–based regional director of the Worker Rights Consortium, explained, the minimum wage in Indonesia varies dramatically from region to region. If a factory moves from Jakarta into a cheaper rural market for labor, its owners can pay a minimum wage about half what they were paying in the capital. “It’s the ideal situation for wage theft,” Gehrt said. “A lot of companies set up shop in Jakarta but shut down and set up in Central Java.” An additional incentive to relocate internally is that the main apparel workers’ union, the All-Indonesian Trade Union-Garment and Textile Federation, is quite ineffectual, and its leadership has been notoriously close to factory owners. And the union is weaker still and far more accommodating to bosses in the interior than it is in the industrial zones that ring Jakarta.

Over the past several years, a few American apparel brands drawing their workforces from factories in Indonesia have stepped up to pay severance for fired workers when the shuttered factories that employed them refused. These include Adidas and Nike, which back in the 1990s was involved in numerous scandals about the treatment of apparel workers in Indonesia but improved its behavior following an international campaign against it.

However, the great majority of international firms didn’t come in for the same P.R. blowback that Nike et al. did over their labor practices—and so had no incentive to reform their larcenous wage regimes. And since they almost exclusively retain their labor forces abroad via the arm’s-length intercession of subcontractors, the big Western brands can maintain an official posture of deniability in the consolidation of the Southeast Asian wage-theft economy.

The WRC argues, straightforwardly, that such practices put global garment brands in violation of their own labor codes. When factories shut down and won’t make legally required payments, the brands must pay workers. The big brands have pledged to work only with responsible factory owners who treat workers fairly, so they should be on the hook, says the WRC’s Scott Nova. He says that wage theft is preplanned and routine, and that the brands are fully aware that closures are built into the factories’ business models. “The big brands have pledged to work only with responsible factory owners who treat workers fairly, and they claim to have robust systems in place to ensure compliance, so they cannot disclaim responsibility,” Nova said. “We are not talking about charity. This is money that is legally required to be paid, and the brands have pledged to uphold the law,” Nova told me. “Workers are paid sub-poverty wages to begin with, and on top of that they get ripped off when the factories close. This is organized theft on a massive scale.”

Nova said that the WRC has tried for years to interest Western journalists in the story but never gets anywhere. “Apparently, editors don’t think it’s interesting,” Nova said. “Blackstone is robbing desperately poor people of $10 million. Apple used wage theft in China to steal tens of millions from electronic workers. ‘So what; it’s boring.’ That’s the type of reply I get when I try to get people to care about this.”

At the new vanguard of apparel-based wage theft now is a major player in the global market: Uniqlo, a big brand in fast fashion. The founder and CEO of Uniqlo’s parent company, Tadashi Yanai, has an estimated net worth of $19.3 billion, making him the second-richest man in Japan. Uniqlo now generates billions of dollars in profits for its shareholders, but it stiffed thousands of workers at Jaba Garmindo—the same factory where Jack Wolfskin sourced its clothing.

The former Jaba Garmindo workers tried to recoup their $10.8 million wage-theft claims through the bankruptcy process, even as secured creditors seized and disposed of the company’s most valuable assets. In the face of pressure from international labor groups, Jack Wolfskin came up with about $38,000—less than one half of 1 percent of the arrears and enough to give 1,963 workers a pitiful $20 each.

While reporting in Jakarta, I visited two industrial zones in the city’s poor suburbs, where many apparel factories are located. Before heading out, I met with Yasinta Ariesti, a program coordinator at Trade Union Rights Centre, an Indonesian NGO, in a small room just inside the entrance to the building.

“I try to be optimistic, but it’s not easy,” Ariesti said. “The number of apparel factories is dropping and so are the number of employees. Your strength is in numbers, and the number of workers is dropping.” Meanwhile, she added, the numbers were rising in hard-to-organize spheres of garment work. “The informal sector of the apparel industry is growing quickly, and it’s very difficult to organize people who work from their homes.”

Ariesti told me that apparel factories frequently close down without notice—which means that workers wake up to suddenly learn that they are unemployed. They often also discover that their former employers have fled the scene. Just a few weeks before our conversation, a Korean-owned factory called PT Dada, which produced for brands like Oshkosh B’gosh, Aeropostale, Adidas, and Reebok, had moved in the middle of the night. Its roughly 1,260 employees went to work in the morning to find the factory abandoned and all the major equipment gone.

Elly Rosita Silaban, the chairwoman of Federasi Serikat Buruh Garment Tekstil (FSB Garteks SBSI), or Federation of Textile and Garment Workers Union in Indonesia, told me a story about another factory that invited its workers for a beach holiday weekend. With the workforce safely out of range, the factory used the weekend to close down and relocate.

One Sunday morning, Darisman Muchamad, the WRC’s Jakarta representative, accompanied me out to the home of a worker who had been axed and cheated out of severance by a factory owned by PT Liebra Permana in an area named Bogor. It took us about 90 minutes to reach the home of the worker, a woman named Wulan Muntarsih, via a combination of taxi, motorcycle, and minibus rides. She was a union leader and had gathered four other former Liebra workers, all women, at her home. Eight other people shared the tiny home—her husband and two of her four kids, a nephew, two sisters-in-law and her parents-in-law, who own it—which was surrounded by neighbors living in shacks made of stone or wood.

Another person who joined us was Nurhayat, an official at the local National Workers’ Union. He hadn’t worked at Liebra but knew the women present who did. He stressed that the wage-theft regime in Indonesia operates in what amounts to an unregulated zone of impunity within the country’s porous regulatory state. “The main issue for apparel workers is that the government doesn’t enforce minimum wage laws, so a lot of factory owners paid less,” he said.

The garment division of the Liebra plant in Bogor, which produced bras and lingerie for H&M, Tommy Hilfiger, Fila, Liz Claiborne, and Bestform, among other brands, closed down in 2018. At its peak it employed more than 5,000 workers, but its staff had been steadily declining for the past few years. When it closed, its local payroll was down to 500 apparel workers. Nothing in Indonesian law prevents factory owners who commit wage theft from continuing to operate nationally, so Liebra still happily and profitably runs other plants elsewhere in the country.

Indonesian courts have found that, in an attempt to avoid paying severance, owners of Liebra cleverly offered new jobs to the former workforce at another factory it controlled. The only problem was that the factory was more than 600 miles from its two factories in the industrial zone I visited, so almost all the laid-off workers were forced to turn down the offer. (A Liebra spokesman told TNR that the company transferred a handful of skilled workers from Bogor to its remote factory in Wonogiri, and that they have stayed on permanently; other transferred workers, though, were only hired on temporary contracts and then let go.) A branch of the national Industrial Relations Court has ruled that the workers should get twice the severance due to them when a factory shutters key operations without filing for bankruptcy.

The Liebra workers have sued to try to get the full back wages and severance they’re owed, so far without success. Muntarsih, who was bottle-feeding one of her children as we spoke, told me that she worked for Liebra for 20 years, and the company offered her four months’ wages and no severance, even though she was legally due 20 months. “Liebra has been pressuring me to take their offer, and it is trying to blacklist me and other people who won’t accept working at other factories,” Muntarsih told me. “A lot of us are unemployed. It’s not hard to find new jobs if you have sewing skills, but [those jobs] pay the minimum wage.” (The monthly minimum wage in the area is just over 3.7 million rupiahs, about $267.)

The other workers would only speak off the record, except for a woman named Lena Santuri. She said she was unemployed and her husband was a motorcycle taxi driver who made 70,000 rupiahs per month—about $5. Santuri said that Liebra’s owner, Tony Permana, goes out of his way to shun legally mandated obligations to his workforce. “He doesn’t want to lose to workers, so he’ll bribe whoever he needs to so he doesn’t have to pay us,” she said.

I asked her if life was better now than it was during the Suharto years. “Back then I earned less money, but prices were lower, so I could buy more,” she replied. “For me it doesn’t matter if we have democracy or dictatorship, I’m poor. That’s why I’m skeptical about politics.”

We took a cab until we were about 30 minutes away from our first destination, the home of one of the ex-Jaba Garmindo workers. We got dropped off along a main road, where two men on motorcycles picked us up, as my local guide and translator had arranged. As we got near to the worker’s home, we passed a huge field of garbage along the roadside, and dozens of people were picking through the trash.

It turned out this was not a garbage dump where poor people scavenged for scraps; it was a trash field where people lived. The site was a dumping ground for factories in the area. Smoke rose from fires at various spots across the field. It was the worst poverty I witnessed in Indonesia—or anywhere else I’ve been.

At another worker’s home, I spoke with a member of the FSPMI, the Federation of Indonesian Metalworkers—the cross-trade industrial union that represented most members of the Jaba Garmindo workforce. I asked if the union fought hard for its members, as I’d heard that some of its local officials had been bought off by management. “FSPMI is a good union at the national level,” he said. “But advocating against the brands, which is what we need, is something new to them.”

I asked whom he planned to vote for in the upcoming presidential election, and what he’d thought of the country’s authoritarian rule. “I’m just a worker,” he said, without anger but with wariness. “I don’t want to talk about politics.”

Several of the workers told me that the brands—including Jack Wolfskin and Uniqlo—would come by on visits ostensibly to oversee working conditions. The visits were shams. “Uniqlo was a priority visitor,” said one former worker, who asked to remain anonymous. “We had to clean up before they arrived.” She was not on hand during a similar Potemkin-style certification visit to the Wolfskin plant, but one of the other workers, who also asked not to be named, was, and he said that some “special preparations” were made then as well.

“I’m very angry at the factory owner because he collected all of the profits and tossed us out like trash,” said the former worker who witnessed the Uniqlo visit. “I’m also angry at the brands, especially Uniqlo, because they demanded good quality and everything on time. To meet their demands, the factory had to buy new, very expensive machinery, and that’s why it went bankrupt.”

For someone who’s now more than ten years dead, Suharto still feels very much like the maximum leader of Indonesia’s wildly unequal political economy; the New Order is now far from new, but its power is everywhere still all too plain. The dictator, his family and followers, and the killers were never held accountable for their actions—and indeed assiduously sought, in the vein of right-authoritarian leaders everywhere, to depict themselves as the true victims of implacably hostile historical and cultural enemies. As a result, today’s Indonesia is still propping up a broad-ranging culture of impunity designed to benefit the country’s ruling elite.

Since Suharto vacated the scene in the 1990s, the country has received high marks for a successful transition to democracy, but on what terms and with what consequences? Democracy—understood in the broader, material sense as a set of meaningful protections of core civil rights such as the ability to earn and secure a sustainable wage across your adult working life—is largely a dead letter for most Indonesian workers. That’s no doubt why so many workers, abused and aggrieved by the capital flight of major garment brands like Jack Wolfskin and Uniqlo, typically fell silent or expressed a world-weary brand of fatalism any time I suggested that they might seek remedies through the Indonesian political system. They know that, despite certain nominal improvements to the electoral process, Indonesia’s politics remain an ominously well-armed plaything of factory owners and other moneyed interests.

As was the case during the Suharto dictatorship, there’s a rigid collaboration between politicians and Indonesian oligarchs. Business executives give money to politicians who win office by distributing money and goods to voters. When they win office, they steal state money to replace the capital they were provisionally given to fund their elections and pass laws that benefit their financial patrons. It’s an arrangement that’s bound to sound familiar to anyone following American politics in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision striking down all functional limits on campaign finance in American elections.

Meanwhile, many members of Indonesia’s political, economic, and religious elite have direct ties to the massacres. Among countless examples, the country’s previous president, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, is a retired army officer who took part in the massacres.

The current president, Widodo, is running for reelection in April and may well lose to Prabowo Subianto, a former general who is a notorious alleged killer and human rights abuser. The son of a carpenter, Widodo is the first Indonesian president who doesn’t hail from the elite and is a force for some incremental and moderate reforms to the country’s corrupt political system and rapacious wage-theft–enabling economic order. At the same time, however, he’s been severely hemmed in by the military and some Islamic groups, even though at the outset of his term he took clear precautions against that outcome by selecting a conservative vice president and naming many military officers to key posts in his administration.

Nonetheless, the old oligarchy has launched an absurd but viciously effective smear campaign against him that accuses him of secretly being a Communist and an atheist. “The fear of being labeled a Communist is as strong now as it was at the height of the New Order,” Winters said. “This accusation is coming from conservative Islamic clerics and powerful elements of the military, the same people who were allied to carry out the 1965 massacres. These two actors disagree about some issues, and sometimes quite strongly, but they are united around the whisper campaign accusing Widodo of being a Communist.”

Indeed, the massacres of 1965 are rarely discussed in Indonesia, because nearly 54 years after the fact, there’s really no safe place to reckon with their legacy, beyond the farcical Jakarta memorial to the putative victims of the failed Communist coup. Various people I talked to said this key part of Indonesian history is not even taught in Indonesian schools.

The filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer, who directed the stunning 2012 film The Act of Killing about 1965 and its consequences, told me he can’t safely travel to Indonesia anymore because he received too many death threats after his movie was released. The head of armed forces publicly warned people not to watch his 2014 follow-up documentary, The Look of Silence.

I asked Oppenheimer why the Indonesian slaughter had been all but airbrushed out of officially sanctioned history in Indonesia and in the United States alike. “Once Suharto achieved victory, the U.S. government went silent, especially given the scope of the killings, and the media presented it as a victory,” he said. “It’s hard to believe mass killings were put in a positive light. But it happened.”

This all leads directly back to another legacy of 1965—namely the fear that keeps workers from organizing to defend their rights and allows factory owners, apparel brands, and venal oligarchs like Schwarzman to beggar the poor and get away with wage theft. The national trauma that dates to 1965 is unresolved and deep seated. The police and military no longer really need to mete out violent discipline or threats of detention and arrest to workers contemplating rebellion on the factory floor. (Though it remains the case that factory owners continue to rely on state violence to intimidate workers throughout Indonesia, as the experience of Nurhayat in the Liebra struggle made all too clear.) The half-suppressed memory of the 1965 trauma usually supplies ample motivation for people to stay on line with punishing production quotas—and to drift into Indonesia’s vast postindustrial army of casualized service workers and scroungers once their factories lay them off and impound their severance and back pay to subsidize Stephen Schwarzman’s Neronic birthday revels.

In his remarkable book, The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965-66, Geoffrey Robinson cites a wide range of countries, including Argentina, Bosnia, Cambodia, Chile, Germany, Japan, Rwanda, and South Africa, that had to confront and reckon with their own horrifying pasts of strongman impunity, untrammeled political violence, and exploitation at the hands of a globalized moneyed oligarchy. “While their records are certainly far from perfect,” he wrote, “all these countries have at least made some halting effort to come to grips with their violent pasts, to seek a shared understanding of that history through the formation of truth commissions, to bring at least some of the perpetrators to justice, to recognize and memorialize past crimes, and to provide some kind of reparations (or at least apology) to the victims of those crimes.”

But as Robinson notes, Indonesia ranks very badly in this regard, and is “in the company of a handful of states notorious for their evasion of meaningful human rights action.” Here he cited China, the Soviet Union, and the United States, “in connection with its genocide against indigenous peoples as well as the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

Nevertheless, even if Indonesian officialdom refuses to confront the massacres committed by Suharto—and even if the country’s elites may push the ghastly former general Subianto into office in the April election—at the grassroots level, people know what happened and who the perpetrators were. “People lost their loved ones, and they cope in different ways,” Hari Nugroho, a lecturer and researcher at University of Indonesia, told me in Jakarta. “They joined a religion or they kept silent.” And they took great pains to shield successor generations from any exposure to the massacres and their toxic political legacy. “That’s why a lot of young people don’t even know that the massacres happened.”