Two years after Clarence Thomas’s bruising confirmation hearing in 1991, The New York Times reported that the Supreme Court justice told two of his law clerks that he planned to serve until 2034. That would give him a record tenure of 43 years on the nation’s highest tribunal. But superlatives were not the reason for his goal. “The liberals made my life miserable for 43 years,” he reportedly told them, “and I’m going to make their lives miserable for 43 years.”

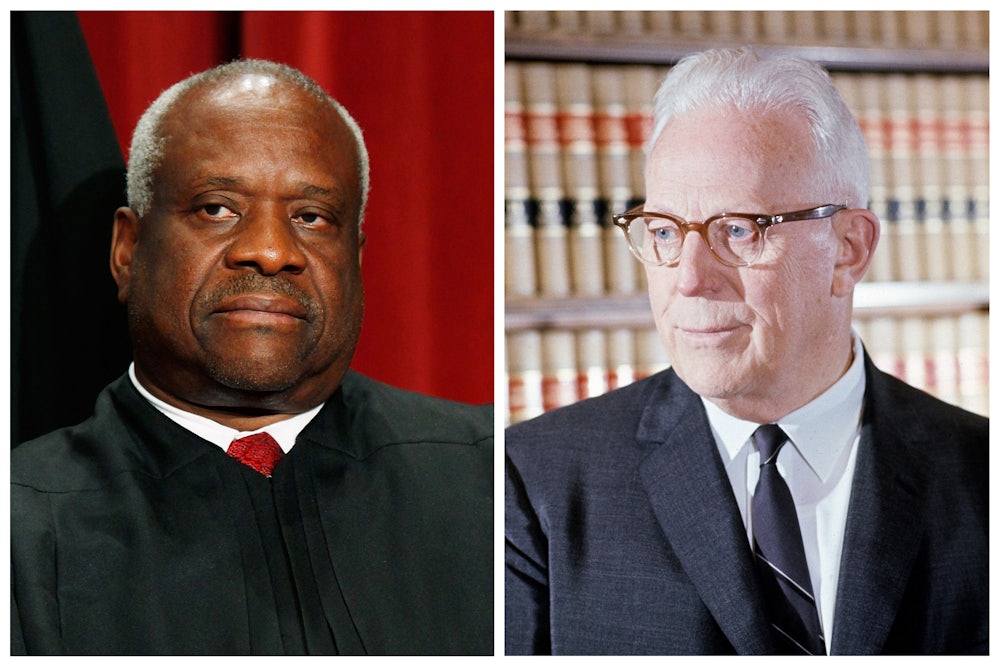

Since joining the court, Thomas has often called for his colleagues to revisit major precedents that he believes are at odds with the Constitution’s meaning. Many of those decisions sprang from the era between 1954 to 1969 when the court’s liberal wing, led by Chief Justice Earl Warren, reshaped American society like no other Supreme Court before or since. Thomas’s quest has often been a lonely one, thanks to the moderation of conservative justices like Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy. But a series of recent dissents from Thomas and his most conservative colleagues shows how he may yet win.

The Warren Court amounted to a third American revolution of sorts, after the original and the Reconstruction era. Its decisions on the allocation of power in American political life helped transform the United States into a liberal democracy. The justices swept away the legal architecture of American racial apartheid—most famously in Brown v. Board of Education, which outlawed segregation in schools, and Loving v. Virginia, which overturned laws against interracial marriage—and upheld federal civil-rights legislation. It broke the rural stranglehold on state legislatures by mandating the one man, one vote principle for legislative districts. Americans accused of crimes gained a bevy of new rights: to an attorney even if they couldn’t afford it, to toss out illegally obtained evidence, to receive any exculpatory evidence obtained by police. First Amendment protections for newspapers and protesters grew stronger, and reproductive rights gained constitutional recognition for the first time in Griswold v. Connecticut.

It was a halcyon era for American liberals, but not everyone was thrilled. The Warren Court’s landmark decisions spurred a backlash on the political right. Social conservatives railed against the court’s rulings against prayer in public schools and legalized access to contraception. Southern whites rebelled against desegregation orders, at times prompting the federal government to enforce the Supreme Court’s decision by force. Libertarians denounced the vast expansion of federal power at the perceived cost to individual liberty. From this medley of opposition grew the intellectual foundations of the modern Republican Party.

In a way, the legal war against the Warren Court has been underway for decades too. The court, after shifting rightward in the 1970s and 1980s, frequently narrowed major precedents from that era. Conservative legal scholars rallied around originalism, a theory of constitutional interpretation that claims allegiance to the original meaning of the nation’s founding charter. Originalists, most prominently Justice Antonin Scalia until his death in 2016, tend to be highly critical of landmark Warren Court rulings for stepping beyond what they think the Constitution allows. With originalism’s rising influence on the high court, the war may reach new heights.

Last month, the Supreme Court rejected a request to hear McKee v. Cosby, a First Amendment case involving disgraced comedian Bill Cosby. Katherine McKee, who publicly accused Cosby of rape in 2014, sued him for defamation after he and his legal team allegedly leaked a letter that disparaged her truthfulness and character. The lower courts dismissed her case, ruling that her allegations against Cosby had made her a “limited-purpose public figure.” Defamation law generally treats public figures like Donald Trump differently than an ordinary private citizen, but also recognizes that private citizens can sometimes become a quasi-public figure when they take part in a matter of public controversy.

The lower courts’ finding makes it much harder for McKee to win a defamation claim against Cosby under the Supreme Court’s current precedents. In 1964, the Warren Court ruled that the First Amendment blocks defamation claims by public figures unless they can prove the speaker acted with “actual malice,” which the justices defined as “reckless disregard” for the truth. The case, New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, arose during the civil-rights era when Southern officials regularly tried to squelch unfavorable newspaper coverage with egregious libel claims.

Thomas, writing only for himself, said the court had correctly declined to intervene in the case. He then went on to suggest that the landmark libel precedent should be overturned. “[Sullivan] and the Court’s decisions extending it were policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law,” Thomas wrote, adding that the court should not continue to “reflexively apply” it going forward. “Instead, we should carefully examine the original meaning of the First and Fourteenth Amendments,” he continued. “If the Constitution does not require public figures to satisfy an actual-malice standard in state-law defamation suits, then neither should we.”

A world without Sullivan would be a daunting one for American journalists. The actual-malice standard gives broad legal protections to Americans when they go public about the misdeeds of the rich and powerful. I noted last December that in countries with lower thresholds for defamation claims like Australia, the wealthy and powerful can wield the legal system as a cudgel against those who try to expose their wrongdoing. Without Sullivan, the states would be able to set their own legal standards for defamation claims, a prospect that President Trump would likely relish.

In February, Thomas also took aim at Americans’ access to legal counsel under the Sixth Amendment. The case, Garza v. Idaho, involved an accused man who asked the Idaho courts to intervene after his lawyer refuse to file an appeal on his behalf. The lawyer declined because Gilberto Garza had waived his right to appeal during a plea bargain. In a 6-3 ruling, the justices said that the lawyer should have filed the appeal when his client requested it, even though the appeal itself was likely doomed. Thomas, joined by Alito and Gorsuch, wrote in dissent that Garza had waived his right to the appellate process itself during the plea bargain, so his lawyer had acted correctly by not filing anything. Then Thomas went even further.

Gideon v. Wainwright, the 1963 ruling that guarantees criminal defendants a lawyer even if they can’t afford it, may be one of the court’s most consequential rulings of the past half-century. It effectively forced states and the federal government to create the public-defender system to provide attorneys for defendants who could not afford one themselves. In a section joined only by Gorsuch, Thomas suggested that Gideon and the rest of the court’s ineffective-counsel rulings since the 1960s should be reconsidered. Instead of reading the Sixth Amendment as guaranteeing legal counsel in all criminal matters, he said the Constitution’s drafters only wanted to bar the government from forbidding a defendant from hiring a lawyer at all.

“It is beyond our constitutionally prescribed role to make these policy choices ourselves,” he wrote. “Even if we adhere to this line of precedents, our dubious authority in this area should give us pause before we extend these precedents further.” With public-defender systems already chronically underfunded, reversing Gideon could prompt some states to shutter them altogether.

Though Thomas had shared this view before, this was the first time another justice had publicly signed on to them. In other areas, however, the court’s conservative wing may be moving closer to his position. The justices heard oral arguments last week in American Legion v. American Humanist Association, a thorny religious-freedom case that centers on a four-story concrete Latin cross in the middle of a Maryland highway. Erected as a World War I memorial in 1925, the cross is owned and maintained by the state government. A group of local plaintiffs say that arrangement violates the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, which generally forbids Congress and the states from privileging one faith over another.

In the 1971 case Lemon v. Kurtzman, the Supreme Court set down a strict test for determining when the government’s involvement in religious matters violates the Constitution. That test is often criticized by conservative legal scholars; the Supreme Court has also drifted away from it in the decades since it was handed down. As I noted last week, the plaintiffs proposed scrapping Lemon and adopting a test that could give the government far more leeway when entangling itself with religion. The justices seemed unwilling to go quite that far in oral arguments last week. But the Establishment Clause’s status quo also seemed rocky. “Is it time for this court to thank Lemon for its services and send it on its way?” Gorsuch asked during oral arguments. Thomas, as is his usual practice, did not speak or ask questions.

It’s worth noting that Thomas and Gorsuch won’t exactly be leading a counterrevolution right away. Justice Samuel Alito joined only one of Thomas’s dissents—in Garza, the Sixth Amendment case—and explicitly refused to join the portion disavowing the 1960s precedents under fire. But he’s made clear his views on the Warren era. In 1985, in a job application to the Reagan Justice Department, Alito wrote that his interest in constitutional law as a college student was “motivated in large part by disagreement with Warren Court decisions, particularly in the areas of criminal procedure, the Establishment Clause, and reapportionment.” He seems to be a likely third vote in any majority opinion that chips away at a Warren-era precedent.

Chief Justice John Roberts has sided with the court’s four liberals more frequently than usual this term, perhaps hoping to shore up the court’s public legitimacy after the corrosive effects of Brett Kavanaugh’s partisan confirmation battle last fall. Kavanaugh himself has yet to make his impact fully felt on the court. In 2017, he delivered a glowing lecture on the jurisprudence of William Rehnquist, Roberts’s predecessor as chief justice. Many legal scholars, Kavanaugh said, “do not know about [Rehnquist’s] role in turning the Supreme Court away from its 1960s Warren Court approach, where the Court in some cases had seemed to be simply enshrining its policy views into the Constitution, or so the critics charged.” Whether Kavanaugh will count himself among those critics remains to be seen.

Kavanaugh’s confirmation also underscored how conservatives enjoy an actuarial advantage when it comes to the Supreme Court. Thomas, the dean of the court’s conservatives, turned 70 years old last summer. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, his liberal counterpart, is 85 and Justice Stephen Breyer is 80. If Democrats capture both the White House and the Senate next year, they may be able to maintain the court’s current ideological balance. If Trump wins re-election, however, it’s likely that the nation’s highest court will drift even further to the right. Some of these landmark precedents may yet survive the Roberts Court’s scrutiny in the short term. But time is on the originalists’ side.