In the summer of 1902, a 20-year-old Puerto Rican woman named Isabel Gonzalez set sail for New York City from San Juan. She was pregnant, a recent widow, and had few economic options in Puerto Rico. Her brother was working in a factory in New York, and her aunt had also recently moved there and married the well-connected Puerto Rican journalist Domingo Collazo. With their help, Gonzalez must have thought, she could make a new life in the city. So that summer, she left her two-year-old daughter with her mother in San Juan, telegraphed ahead to her family to meet her, and got on a ship with just eleven dollars in her pocket. She could not have known that her arrival in the mainland United States would set in motion a controversy that would change how we interpret the U.S. Constitution itself.

When Gonzalez boarded her ship in San Juan, she likely would have expected to be admitted without trouble in New York. Her aunt, after all, had made the same trip just a year before. And American officials carefully avoided treating Puerto Rican immigrants as aliens because they did not want to give anti-imperialist politicians, especially those in the Democratic Party, a way to attack the new colonial system the United States was developing to govern Puerto Rico, Hawaii, and the Philippines. But unfortunately for Gonzalez, U.S. immigration policy changed sharply while she was sailing north. Under new rules, Puerto Ricans were to be treated like immigrants from foreign countries. So instead of meeting her family on the docks in New York harbor, Gonzalez was sent to Ellis Island, where immigration officials detained her as an unmarried mother “likely to become a public charge.” Her uncle offered to provide for her, but inspectors eventually classified her as an undesirable alien and refused to let her in.

Gonzalez was a proud and intrepid woman, and she fought for her right to enter the country. She even hid the fact that she got married once she was out on parole—which would have allowed her to stay in New York but also would have ended her court case—so that she could continue her legal battle for citizenship. With the help of her uncle and the New York lawyer Frederic Coudert, she appealed her case all the way to the Supreme Court. The Court’s decision was fundamentally ambiguous—it held that she was not an alien and so could enter the country, but it did not decide whether she was a U.S. citizen. That very ambiguity, however, helped clarify the status of Puerto Ricans under a burgeoning U.S. empire at the turn of the twentieth century: more than foreigners, but less than full citizens with genuine self-determination and the complete suite of constitutional rights. Though Congress has subsequently extended citizenship to Puerto Ricans by statute, Gonzalez’s case still stands as Supreme Court precedent for what rights the Constitution guarantees to Americans living in the territories, including Puerto Ricans today. It remains the case that Puerto Ricans cannot vote in presidential elections, that their representatives cannot vote in Congress, and that the federal government can and does provide substantially less funding for programs like Medicaid in Puerto Rico than it does in the states.

Sam Erman tells Gonzalez’s story in his absorbing new book Almost Citizens: Puerto Rico, the U.S. Constitution, and Empire. In Erman’s account, Gonzalez is one of a number of activists who fought a 20-year battle to redefine the Constitution after the United States acquired Puerto Rico and the Philippines in 1899 out of the Spanish-American War. Erman is a law professor at the University of Southern California with a background in American Studies, and Almost Citizens shows off both his range and his substantial chops as a historian: The book is deeply researched and densely footnoted, but Erman’s writing is also lively and lucid, and he has an eye for catchy stories and compelling characters. Most importantly, he has recovered a crucial history of the struggle over democracy, rights, race, and gender in America, a set of conflicts we have not left behind.

The contest over Puerto Rican citizenship at the turn of the twentieth century, Erman argues, helped bring an end to the more racially inclusive constitutional order ostensibly created by Northern Republicans after the Civil War. Up until the Spanish-American War, it was widely understood that the Fourteenth Amendment, passed during Reconstruction, made it impossible for America to hold an empire. The Amendment guarantees that all persons born in America will be “citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” In the late nineteenth century, lawyers, judges, and politicians all read this to mean that any new territory acquired by the United States would eventually become a state and that everyone who lived there would necessarily be a citizen. It was a key feature of what Erman calls the Reconstruction Constitution that citizenship and statehood inevitably follow the flag.

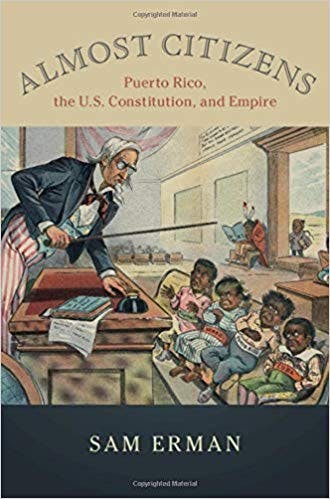

In the wake of the Spanish-American War, though, racist politicians in Washington, D.C. did not want to incorporate Puerto Rico, Hawaii, and the Philippines into the United States. They wanted to hold the territories for economic and military purposes, to be sure. But they were unwilling to give the substantial non-white populations on the islands status as equal citizens. The legendarily white-supremacist Senator James Vardaman of Mississippi declared, for example, that Puerto Ricans would have to be “held against their will” because they were too uncivilized to “understand the genius of our government” and they would “menace the nation with mongrelization.” One of the many fascinating and deeply unsettling editorial cartoons that Erman reprints, titled “The White Man’s Burden (Apologies to Kipling),” expressed a similar white nationalist panic. It portrayed a weary Uncle Sam carrying caricatures of brown-skinned natives, clutching clubs and spears and labeled “Filipino,” “Porto Rico,” “Cuba,” “Hawaii,” and “Samoa,” up a steep mountain labeled “Barbarism” and “Ignorance.” The cartoon ignored the substantial racial diversity in Puerto Rico and the complicated political relationships between racial groups that Erman now skillfully maps. But that was the point: to reduce the islands to a derogatory stereotype of blackness and thereby imply that their residents could never rule themselves.

Puerto Ricans, however, did not simply acquiesce to second-class status. They organized and demanded their rights. The power of Erman’s book lies in the fact that he not only tracks the members of Congress and the Supreme Court justices who debated whether Puerto Ricans should have constitutional rights, but he also follows the Puerto Rican politicians, activists, journalists, lawyers, labor leaders, and ordinary people—like Isabel Gonzalez—who achieved a series of partial victories in Congress and the courts that changed American history.

In addition to Gonzalez, Erman focuses mainly on the works of the sophisticated lawyer and congressional representative Federico Degetau y González, the radical socialist labor organizer Santiago Iglesias, and Gonzalez’s uncle, the sometime-revolutionary and journalist Domingo Collazo. Each man adopted a series of legal and political strategies during the long fight for citizenship, and in Erman’s prose, their personal and collective struggles come alive. Iglesias, in particular, reinvented himself repeatedly, first as a revolutionary anarchist in Cuba, then as a labor leader in Puerto Rico, where he was jailed for organizing strikes, and finally as a respectable politician when he became Puerto Rico’s elected Resident Commissioner, a non-voting member of the United States House of Representatives.

On a more quotidian level, Erman amusingly reports that Collazo worked to build an alliance with the Puerto Rican politician Luis Muñoz Rivera by writing a positive review of Rivera’s book of poetry, Tropicales, and sending his review to Degetau; Degetau sent back a copy of his own book, Cuentos para el viaje. Gonzalez, for her part, remained active even after her court case, as she and Collazo published a series of letters to the editor in the New York Times demanding Puerto Rican rights.

As Erman’s title indicates, these activists achieved a partial success, winning status as “almost citizens.” Iglesias formed a bond between Puerto Rican workers and the American Federation of Labor and used the alliance to win basic labor rights. Degetau cleverly managed to get the Supreme Court to admit him as a member of the Supreme Court Bar and thereby implicitly affirm that he was a citizen, since only citizens could argue before the Court. Collazo eventually turned stateside Puerto Ricans into a powerful voting bloc in New York City who could lobby their members of Congress for better conditions on the island, an effective end-run around the lack of voting rights for Puerto Ricans back home.

Yet Puerto Rican gains were painfully circumscribed. The Supreme Court handed down a series of explicitly racist decisions in the Insular Cases, a string of opinions—Gonzalez’s among them—that created a new status for so-called unincorporated territories where the Constitution does not apply in full. These decisions unraveled the Reconstruction Constitution and its citizenship guarantee. In Downes v. Bidwell, most famously, the Court said in 1901 that if new territories like Puerto Rico “are inhabited by alien races,” then “government and justice, according to Anglo-Saxon principles, may for a time be impossible.” The Constitution did not guarantee self-government. The racist logic of the Insular Cases, Erman argues, was a part of the Court’s simultaneous attack on Reconstruction in the American South, as it legalized separate but equal in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 and allowed the disfranchisement of black voters in Giles v. Harris in 1903. Consequently, when Congress collectively naturalized all Puerto Ricans in the Jones Act in 1917, partly for fear of a German attack in the Caribbean, “it was the all-but-rightsless citizenship that Democrats had pioneered for African Americans in the South” that was finally extended to Puerto Ricans.

Erman’s story is a critical addition to our understanding of Reconstruction and its afterlives. Alongside the familiar tale of the fall of Reconstruction, Erman shows how the Reconstruction Constitution temporarily prevented a formal American empire, and then how empire arose hand-in-hand with Redemption and Jim Crow, subjugating racialized and minoritized populations on the mainland and the islands alike. At the same time, resistance to Jim Crow and empire could be productively interlinked—the Puerto Rican writer Arturo Schomburg was a leader in the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, while W.E.B. Du Bois decried the brutal American treatment of the Philippines in The Souls of Black Folk in 1903 and called for labor rights and self-determination in Puerto Rico after World War II. The deep affinity between antiracism, anti-imperialism, and labor rights is no less important today.

The history recounted in Almost Citizens, that is, remains disturbingly resonant. Puerto Rico continues to suffer from its status as what the eminent Puerto Rican jurist José Trías Monge called “the oldest colony in the world.” In the wake of the Great Recession, a financial control board was put in charge of critical decisions in Puerto Rico and has cut public health spending, slashed the minimum wage, and shuttered schools. After Hurricane Maria devastated the island, federal shipping laws made it more difficult to bring in aid, the lack of healthcare funding hampered recovery, and the disaster almost certainly received less attention than if Puerto Rico were a state with votes in Congress and the electoral college. More broadly, conflicts over race, immigration, and birthright citizenship, not to mention the gender discrimination Isabel Gonzalez faced as an unwed mother, continue to occupy a painfully central place in American politics. But Erman also shows—contrary to the conservative view that the Constitution is limited to its original meaning—that activists like Isabel Gonzalez can change how we understand our most basic laws and so can bend the arc of history, at least a bit, toward justice. That possibility should give us hope for the future.