Ben Terris calls it “Pundititis.” Democrats still haven’t recovered from the trauma of Hillary Clinton’s loss to Donald Trump, and it’s causing them to wring their hands about every candidate emerging to challenge him in 2020. So the Washington Post reporter coined this term to describe “a virus affecting the nervous system of Democratic voters that was born out of the 2016 elections. Those infected find themselves unable to fall in love with candidates, instead worrying about what theoretical swing voters may feel. Signs of Pundititis include excessive electoral mapmaking, poll testiness, and an anxious, queasy feeling that comes with picking winners and losers known as ‘Cillizzasea’”—a dig at Terris’s former colleague.

This is not an inaccurate diagnosis of the Democrats today. Terris is also right to attribute this malady not only to the results of the last presidential election, but to the mainstream media’s analysis of the emerging Democratic field. Reading much of the punditry of late, one might expect the primary season to be the political equivalent of WWE’s Royal Rumble, a massive free-for-all in which the candidates beat each other to a pulp in a race to the left, leaving one wobbly—and perhaps not very “electable”—candidate standing for Trump to effortlessly defeat.

Fear not, afflicted ones. While Democrats are understandably scarred by 2016, the party has learned its lesson: There will be no coronation this time around, no stark contrast between two candidates representing their respective wings of the party. And while the 2020 primary thus will be crowded, it will be a marked contrast to the “clown car” Republican primary of 2016. For the next year, the Democrats will showcase a party that looks and sounds very different not only from the GOP, but from the Democratic Party of just a few years ago. Rather than a moment of anxiety, this should be a moment of hope and pride—and Republicans should be the ones feeling queasy.

Democrats are gearing up for a long, contentious primary season. Nine major candidates have already entered the fray—most recently South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, an openly gay 37-year-old military veteran, who announced on Wednesday. By the summer, that number may have ballooned to two dozen or more. That vast field will reflect the Democratic Party in all of its diversity, from ideology to race to sexual orientation to, yes, age. But that has some Democrats nervous that the unfolding contest will distract from the only thing that matters: beating Trump.

The New York Times’ Jonathan Martin characterized these concerns thus: “Will candidates sprint to the left on issues and risk hurting themselves with intraparty policy fights and in the general election? Or will they keep the focus squarely on Mr. Trump and possibly disappoint liberals by not being bolder on policy?”

This is certainly how some Democrats see it: that the candidates can either engage in a costly intraparty fight about issues like Medicare for All and the Green New Deal, or they can focus their fire on the real enemy. The urgency to distinguish oneself from two dozen competitors suggests it will be more the former than the latter. But does that necessarily mean whoever emerges from this scrum will be weakened by it? Couldn’t the opposite be true? Might the nominee be even stronger for their contest against Trump?

Not if the nominee is unelectable, say the pundits.

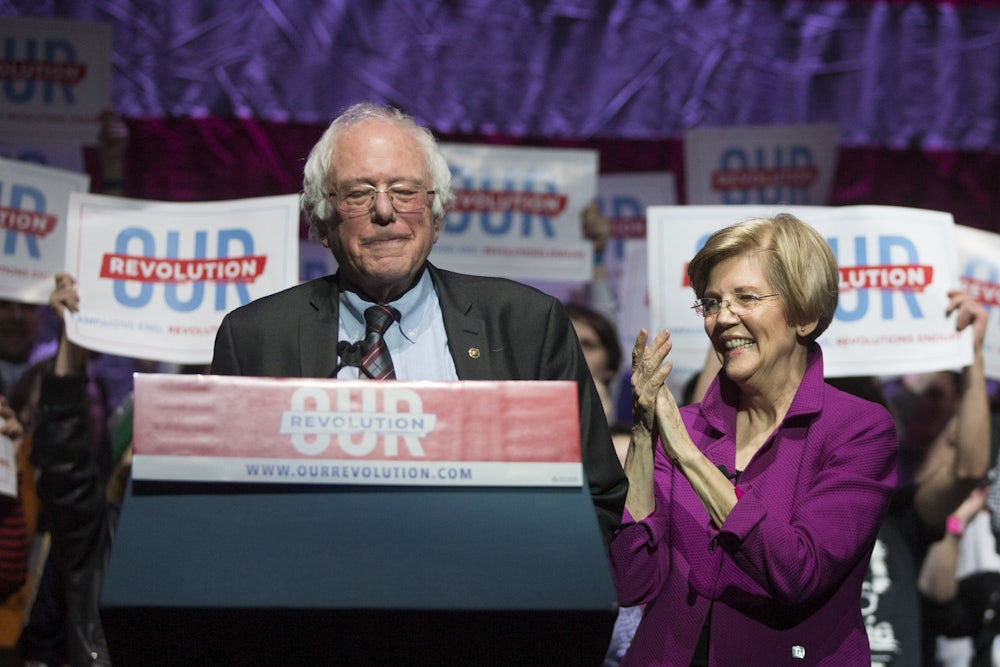

This concept of “electability”—of who is best positioned to win the general election, as opposed to the primary—has driven much of the discussion about the Democratic contenders. Some pundits have even gotten scientific about it: CNN’s Harry Enten crunched the numbers to determine that Amy Klobuchar and Sherrod Brown are electable, while Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders are not.

But others have rightly questioned such analyses. “How, exactly, can anyone tell who the strongest candidate is before an election?” Terris asked. “The simple answer is, they can’t.” Hillary Clinton “was so ‘electable’ that she nearly cleared the field,” he added. “Then she wasn’t elected.” Trump, conversely, was seen as unelectable from the moment he entered the GOP primary until the evening of November 8, 2016. As New York magazine’s Eric Levitz has argued, “Electability arguments have always been handy stalking horses for substantive disagreement.” Which is perhaps why leftist candidates like Warren are being painted as unelectable, while potential centrist ones like Beto O’Rourke and Joe Biden are being treated as Trump’s most formidable foes.

In the end, the gauntlet of the Democratic primary will be the best vehicle for determining who the party’s best candidate is. And there are plenty of reasons to believe that gauntlet won’t be as taxing as some fear it will be.

The 2016 contest between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders was much tamer than it was made out to be. All but a quarter of one percent of the two candidates’ advertisements were positive ads. The authors of Identity Crisis found, moreover, that “Sanders’s success was not so much about capitalizing on an early reservoir of discontent with Clinton. It was about building support despite her popularity in the party.” A higher percentage of Sanders voters voted for Clinton in 2016 than Clinton voters did for Obama in 2008. For all the ink spilled about the acrimony between “Bernie bros” and Clinton die-hards, the primary almost certainly did not play a major role in her loss to Trump.

The 2020 primary undoubtedly will fuel a lot of animosity online, too, but there’s no reason to believe that it will be particularly acrimonious among the candidates themselves. There appears to be broad agreement, both on the need to repudiate the Trump administration and the necessity of passing bold reforms. Moreover, there appears to be no Trump-like outsider waiting in the wings to upend the race and cause an existential crisis in the party.

Yes, there will be intense scrutiny of the candidates—from Kamala Harris’s mixed record as a federal prosecutor to Joe Biden’s support for overly punitive crime bills—but that’s to be expected, and necessary. There’s no reason to believe that a lengthy debate about ideological differences in the party will be harmful. Democrats have been engaged in exactly that for the past two years, and they have paid little to no political price. They won 40 House seats in a historic midterm election, and every well-known Democrat currently leads Trump in early 2020 polling.

The policy questions that remain—on universal health care, humane immigration, economic redistribution, and so on—are ones worth debating, not just as a party but a country. The Republicans are largely bankrupt of ideas, leaving Democrats alone to put forth concrete, comprehensive proposals for fixing America’s most vexing social and economic problems. Given the unpopularity of Trump’s agenda, what could be more electable than that?