A few weeks after President Donald Trump moved into the White House, he received a memo from one of his biggest campaign donors: Robert Murray, the CEO of Murray Energy, America’s largest private coal company. Emblazoned with the words “Action Plan,” it was essentially a wish list of all the environmental regulations Murray wanted Trump to get rid of.

Nearly two years later, Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency is on track to fulfill almost all of Murray’s requests. And the Senate is on the cusp of allowing one of Murray’s most trusted former lobbyists to lead the effort.

On Wednesday, the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works held a confirmation hearing for Andrew Wheeler, Trump’s nominee to run the Environmental Protection Agency. Wheeler has been effectively running the agency as acting administrator since July, when Scott Pruitt resigned amid a deluge of ethical scandals. But Trump only formally nominated Wheeler to lead the EPA last week, triggering a confirmation process that Democrats are using to shine light on an unsavory fact: As a lobbyist for Faegre Baker Daniels, Wheeler earned more than $700,000 working for an industry he’s in charge of regulating.

The Republican-controlled Senate is unlikely to care about this potential conflict of interest, because they’ve confirmed Wheeler before; his ascent to EPA acting administrator was an automatic promotion from his Senate-confirmed role as deputy administrator. But Democratic Senator Sheldon Whitehouse used Wednesday’s hearing to argue that Wheeler had hidden information from the Senate about his relationship with the coal company.

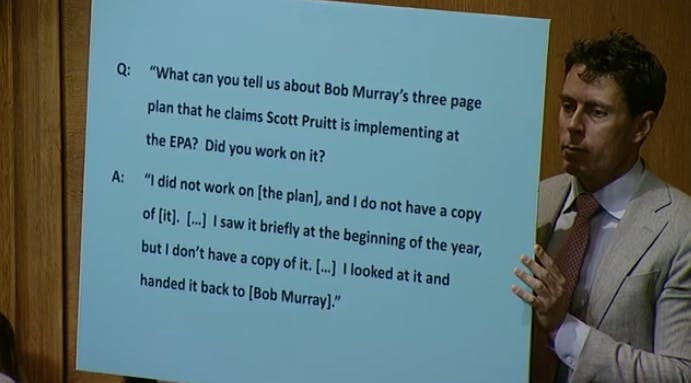

During his confirmation hearing in November 2017, Wheeler said he “did not work on” Murray’s “Action Plan” for Trump, did “not have a copy” of it, and that he only saw the plan “briefly at the beginning of the year.” These comments were featured Wednesday on a large poster board held by a Whitehouse staffer.

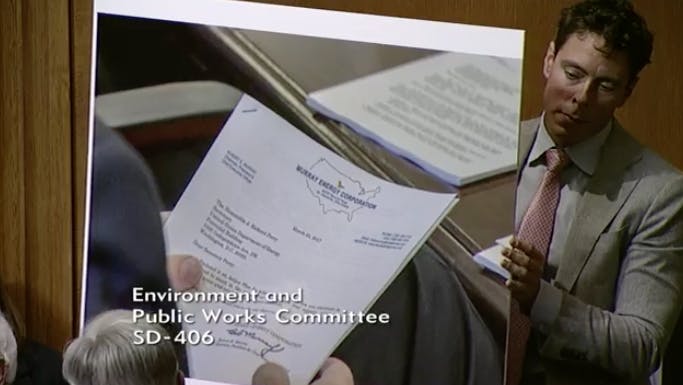

As The Washington Post later revealed, Wheeler attended a meeting in March 2017 with his then-client, Murray, and Department of Energy Secretary Rick Perry. “The action plan was right there in the room,” Whitehouse said while his staffer displayed the photographic evidence.

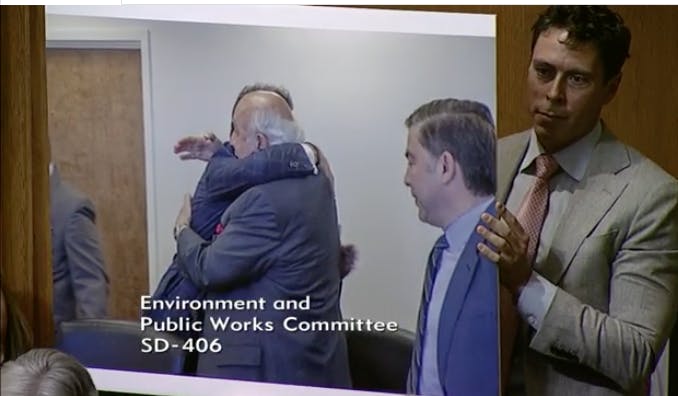

Whitehouse then showed a photo of Perry and Murray at the end of the meeting, embracing in a “bear hug.”

“That’s not me, though,” Wheeler said.

“No, that’s your client, Mr. Murray,” Whitehouse replied.

Good government advocates say it’s not inherently unethical for a former industry lobbyist like Wheeler to lead the EPA. What’s unethical, they say, is if the former lobbyist continues to work for the benefit of their former client instead of the public.

Murray seems to believe Wheeler will continue to do what he wants. “He worked for me for 20 years,” he told Politico last year. “Didn’t want to lose him. But the country has him.” And so far, he’s right. As Mother Jones reported on Wednesday, “The last major action Wheeler took before his agency shut down late last month was remove the legal justification for the EPA’s regulation for mercury, arsenic and air toxics, a move that weakens the EPA’s position in a court case pursued by, yes, Bob Murray.”

The key question for the Senate is whether Wheeler, as the head of the EPA, would willfully ignore the public interest in order to please his former client. Senate Democrats certainly think he would, which is why they spent much of their time Wednesday grilling Wheeler on climate change and criticizing him for weakening several Obama-era rules to limit greenhouse gas emissions.

Wheeler has proven to be a quieter, less controversial figure than Pruitt—and potentially a more effective one. Under Wheeler’s rule, the EPA has proposed weakening methane pollution limits for oil and gas producers and air pollution limits for cars. The agency has also proposed new greenhouse gas regulations to replace the ones implemented by Obama’s EPA, which could be worse for the climate than having no climate rules at all.

Pruitt was planning on doing all those things, too. But many have argued that Wheeler understands the administrative and legal processes better than Pruitt, and thus can implement deregulatory rules that more effectively benefit industry and withstand court challenges. And unlike Pruitt, Wheeler hasn’t been making daily headlines for booking expensive first-class travel, keeping secret calendars, or installing $43,000 soundproof booths.

Wednesday’s hearing didn’t alter that impression. Wheeler proved that he’s deeply knowledgeable about the energy industry and EPA regulations, and that he’s more politically adept than his predecessor. When Senator Bernie Sanders asked him about climate change, he did not deny its reality. “I would not call it the greatest crisis, no sir,” Wheeler said. “I would call it a huge issue that has to be addressed globally.” It was an innocuous response that lent itself neither to outraged headlines nor furious tweets from his soon-to-be-boss.