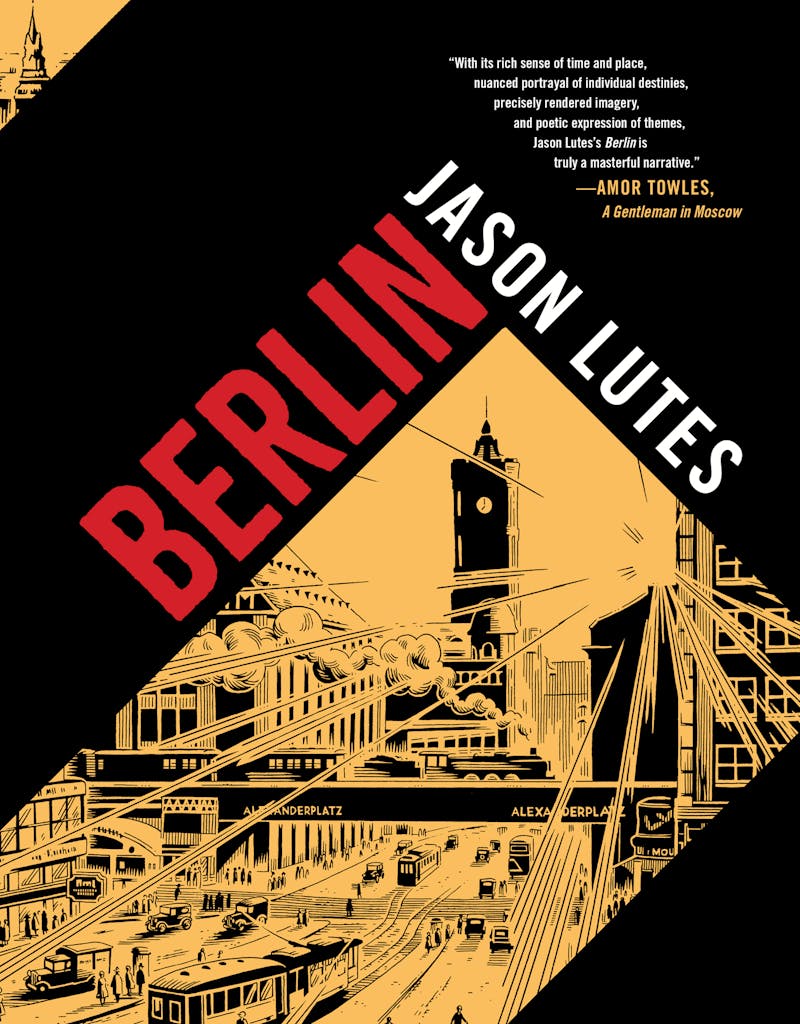

Jason Lutes first started drawing Berlin, his epic graphic novel about the disintegration of the Weimar Republic, in 1996, when the topic seemed an esoteric choice for an American storyteller. The winding down of the Cold War brought with it an ostensible closure of the ideological battles of the early 20th century, leading some of the more triumphalist partisans of capitalism to proclaim nothing less than the end of human history. The future seemed more or less certain: America’s free-market, liberal democratic model would continue to prevail as the best of all possible worlds.

Yet in going back to the apparently irrelevant past, Lutes became an inadvertent prophet. The cartoonist patiently drew his story in short, irregularly released pamphlets, gathered together every few years in paperback collections. When he finally finished the project and codified it in a hefty hardcover in 2018, what had once been antiquarian was now urgent. In the fraying and polarized America of Donald Trump, the Weimar Republic looks more like a mirror than a fading photograph.

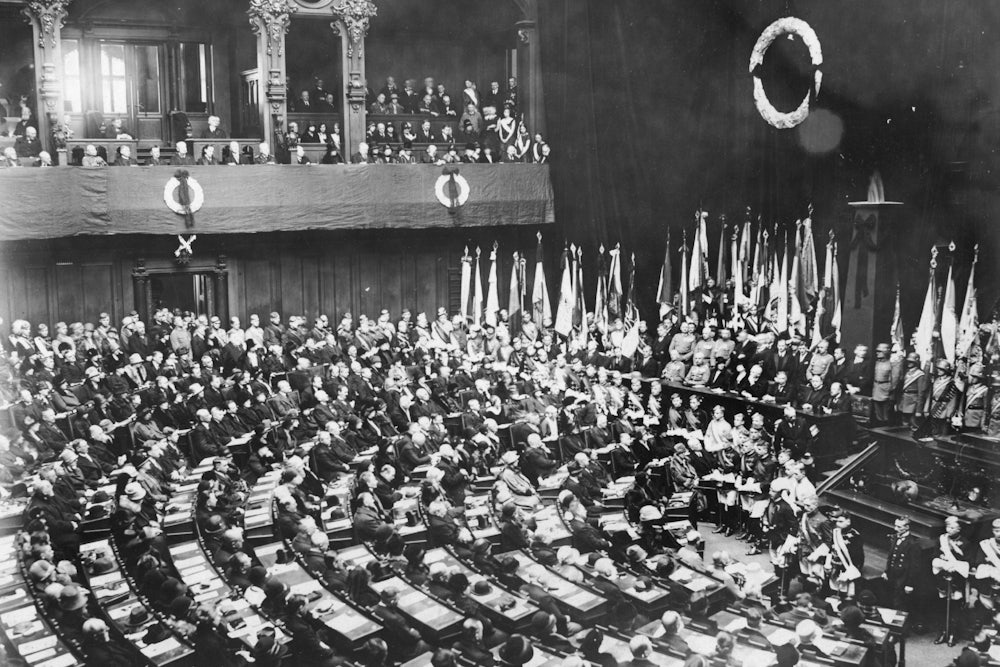

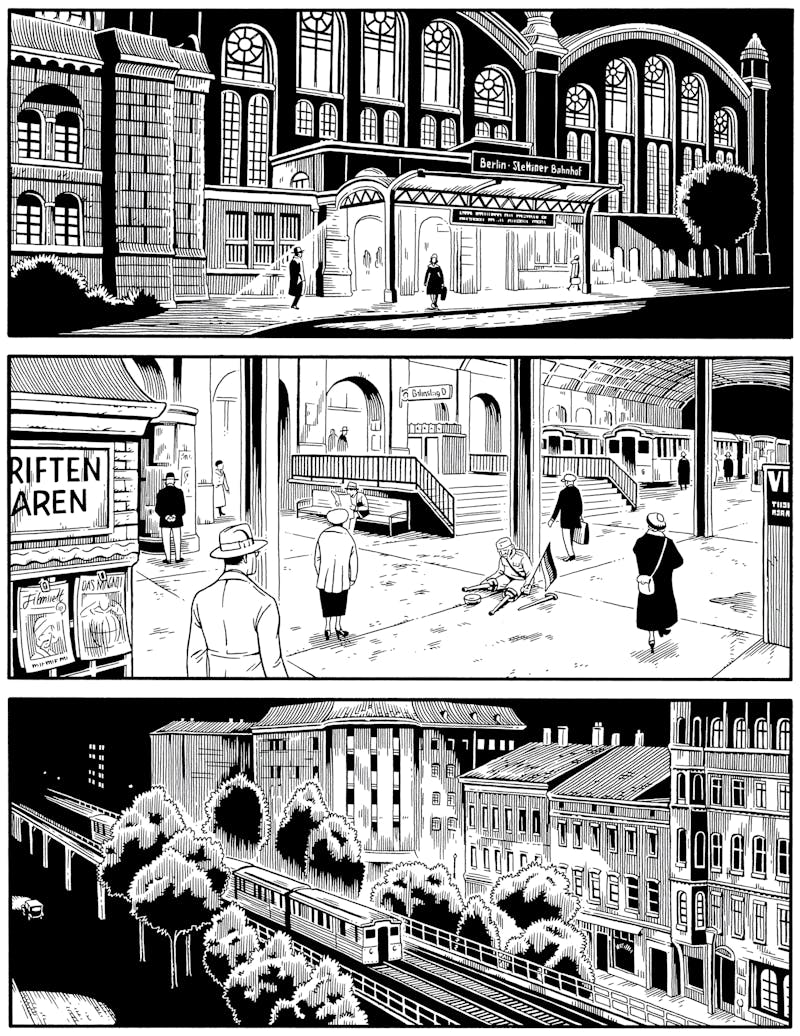

When I first started reading Berlin more than two decades ago, I primarily admired it as a bravura feat of historical reconstruction. Everything—the trains, the buildings, the fashion, the faces—looked right, a testament not just to archival research but also, more importantly, to a style that channeled the imagery of the era. Lutes’s clean, brisk cartooning owes much to Hergé (the creator of Tintin), but there is more than a dash of noir taken from German Expressionism and the woodcut novels that flourished in the 1920s and 1930s (notably those by artist Frans Masereel). The style has an uncanny aptness, as if the book were a product of the very period it surveys.

The book’s physical presence is also a marriage of form and content. In size and weight, Berlin is a building block of a book, reminiscent of the cobblestones, bricks, and concrete slabs that make up the titular city. Cartoonists refer to the white spaces between the panels in a graphic novel as “gutters,” and the street metaphor is particularly appropriate for Berlin. Reading a graphic novel, especially one as dense with geographical information as Berlin, is akin to deciphering a map. The inside cover of Berlin is, in fact, a map of the city, which reinforces the experience of the book as a kind of urban guide in narrative form.

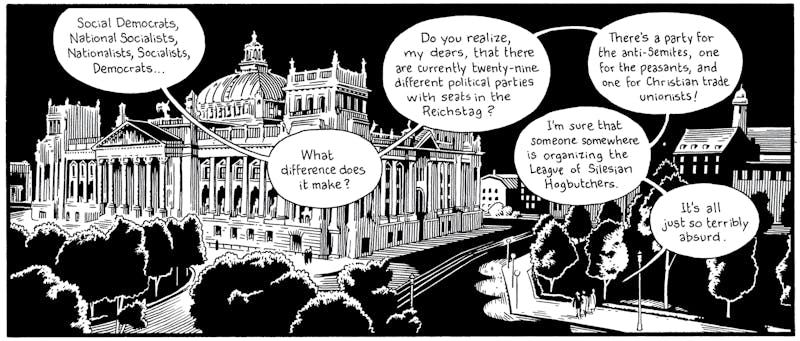

Still, in reading the whole of Berlin, the immersion in a historical urban environment is secondary to the political dilemma that confronts the characters. Berlin features a large and diverse cast: workers and plutocrats, communists and fascists, bewildered liberals and political activists, Jews and anti-Semites, pacifists and street fighters. What unites them is the shared experience of living in a crumbling democracy, where economic chaos, distrust of the established order, and rising violence all work to destroy social cohesion. On a personal level, this means the characters are all tested, again and again, to show empathy, and even the best of them sometimes fail these tests. But the redemptive thrust of the book comes from the resilience of solidarity and hope even in the darkest times.

Indeed, Lutes sees in the Weimar Republics’s failure an opening for genuine creative excitement. The two sides are embodied by the main characters of Berlin: Kurt Severing, a jaded journalist, and his sometime lover Marthe Muller, a young woman who comes to the city to study art. Even as Severing is baffled and shattered by the rise of political extremism, Muller finds pleasure in the city’s flowering of sexual diversity (briefly taking a lover who we would now call a trans man) and aesthetic pleasures (especially a visiting band of African American jazz musicians), which are the direct result of the collapse of suddenly outmoded traditions.

It’s not an accident that Severing and Muller have different experiences of the city. Berlin belongs to the great tradition of the urban novel, which runs from Dickens’s Bleak House to Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz. But as the critic Roger Sale noted in 2000 in the journal Left History, this tradition is highly gendered. Sale wrote that “the high modern conviction that cities are breeding grounds for alienation and despair” tends to come from male writers and filmmakers.

Sale pointed out that we should “[s]et against all that: Lucy Snowe coming to London in Charlotte Bronte’s Villette, or Toni Morrison’s account of southern blacks coming to Harlem in Jazz, or Mrs. Dalloway setting out across London to order her flowers, or Martha Quest coming to London at the opening of The Four-Gated City. All these women characters and writers acknowledge the reasons for alienation and despair, the overwhelming confusion of large cities, but they know also a sense of richness, of possibility, in the very qualities the men deplore.”

The achievement of Lutes’s Berlin is that it combines both sides of the gender divide in urban fiction. In so doing, it offers a more comprehensive way of looking at our own troubled times, which can easily invite despair and resignation. If fascism is a death cult, then opposing it has to include not just political organizing, but also a positive alternative of a good life. Lutes offers just that: His Berlin is a city of hope as well as pain. He doesn’t shirk from depicting the rage and violence that brought down Weimar democracy, but he also shows the heroism and joy that came from standing against the rise of fascism, from people trying to live decently, freely and creatively.